MSF Dr. Deirdre Lynch describes her experience in South Sudan's Batil camp, where MSF provides care to some 38,000 Sudanese refugees.

Dr. Deirdre Lynch, a native of Ireland, currently works with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in South Sudan’s Upper Nile State. She’s part of the team at the Batil camp, where 38,000 people have sought refuge from fighting and violence in neigboring Sudan.

Batil is one of several camps in Maban country where a collective population of 110,000 Sudanese refugees is living. Many have been there for more than a year. More than 75,000 additional refugees from Sudan are in Unity State’s Yida camp as well.

In observation of World Refugee Day on June 20, Lynch describes life in Batil and the challenges facing the refugees and the MSF team trying to provide life-saving medical care in an extremely tough environment.

First Impressions

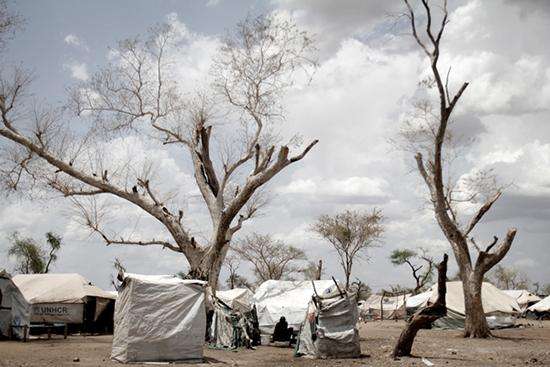

I had some images in my mind of what to expect before I arrived, but seeing the reality of a camp that is home to 38,000 refugees, combined with the tough environmental and living conditions here, was initially overwhelming.

Batil camp is situated in Maban County, in the northeast of South Sudan (the world's newest country) and on the border with Sudan. During the dry season, the land is arid and covered with dusty clay soil. But the camp is located on a flood plain, and after rainfall the result is thick glue-like mud everywhere. Stagnant pools of water are the perfect harbor for many diseases, and, of course, mosquitoes.

Health Care on the Front Lines

In our field hospital, MSF is providing 24-hour health care services for the refugee population of Batil and Gendrassa camps. The living conditions in this setting naturally leave the refugees in a very precarious state health-wise. The care that we provide here spans a broad range of needs from looking after newborns to general pediatrics, to maternity care, to general adult medicine, a nutrition program, and also mental health.

On a weekly basis, we see on average 1,000 patients, both adults and children, with illnesses such as pneumonia, diarrhea, dehydration, and malnutrition. We care for patients with kala azar, a disease endemic in South Sudan and the second largest global parasitic killer after malaria. We also see people suffering with other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), brucellosis, and typhoid.

Recently we treated several children with measles; this week MSF is leading a mass measles vaccination campaign in the camp to stem the outbreak. We also treat people who have sustained injuries due to the living environment—burns from open cooking fires and complications from snake bites or scorpion stings are common.

Our outreach teams, who have their fingers on the pulse of the camp, see an overall improvement in the nutritional health of the children. The work MSF is doing here is visibly making an impact and childhood mortality rates are now much lower compared to this time last year. The health of the population has definitely improved but it will always be fragile in this environment.

Challenges

The population here will be very vulnerable in the rainy season over the next few months. The tents and plastic sheeting will only provide limited protection from the heavy rains. Flooding is likely and we expect to be very busy looking after patients with multiple illnesses.

There are many moments here that are heartbreaking. Witnessing the death of a child affects us all. I particularly remember one seven-year-old girl we treated recently for severe kala azar and malnutrition who succumbed to the illness despite our best efforts. This little girl had a fighting spirit and even in the days before she died would ask for a spoon of sugar from the staff before she would take her medicines. She made an impact on all of us who cared for her.

Maternal deaths are also extremely sad to see. The hepatitis E infection in pregnant women has a mortality rate of approximately 20 percent and many young children are left in the care of the extended family if the mother dies. The hepatitis E outbreak caused a lot of fear within the camp and had a significant impact on the physical health of the population.

Stoicism of the Refugees

MSF employs many refugees to work in our clinic. Ahmed [name changed to protect anonymity] is a 24-year-old ward assistant who helps with patient care in the clinic. He is a bright young man and a great colleague to work with. Last year he left Blue Nile State, in Sudan, with his wife and three children, along with his parents and siblings. Some of his extended family members had already moved to Maban County, walking for weeks to escape the fighting in Blue Nile.

Ahmed becomes emotional when he talks about a close family member who was shot when their village was attacked. He finds it difficult to talk about the suffering he witnessed and he worries about his family and friends back home who did not leave.

Ahmed wants to educate himself further and is determined to attend nursing school. He has plans and dreams. For now though, he has made his home here in the camp and is trying to move forward for himself and his family. I asked him how he copes with the current situation. He replied, “If I think about how hard everything is here it just becomes ten times harder.”

He is trying to keep positive to rebuild his life. Ahmed for me symbolizes the refugee’s stoic, resilient spirit against all the odds.