In Kunduz, a fully functioning hospital managed and operated solely by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was specifically targeted by a party to a conflict, resulting in the largest loss of life of MSF staff since the Rwandan genocide, and the largest ever involving an aerial attack.

The following contains an abridged version of MSF’s initial internal review of events before, during, and after the October 3 airstrikes on MSF’s hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan, along with a discussion of MSF’s response. The review was based on debriefings with MSF national and international employees, internal and public information, emails, and phone records. (The full review can be found at www.kunduz.msf.org.)

Background

MSF opened the Kunduz Trauma Center (KTC) in August 2011. The only facility of its kind in northeastern Afghanistan, the KTC provided high-quality, free surgical care to victims of general trauma, including traffic accidents and conflict-related injuries.

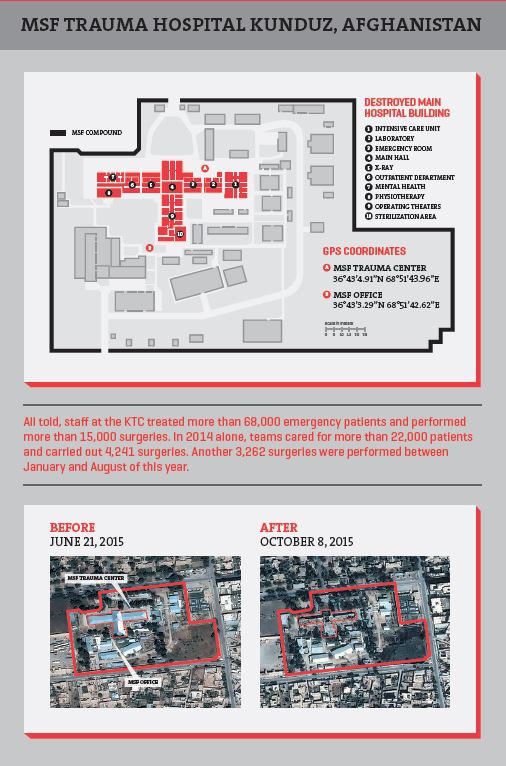

All told, staff at the KTC treated more than 68,000 emergency patients and performed more than 15,000 surgeries. In 2014 alone, teams cared for more than 22,000 patients and carried out 4,241 surgeries. Another 3,262 surgeries were performed between January and August of this year.

Before opening the KTC, MSF participated in comprehensive negotiations with all parties to the conflict, discussing the nature of our work at length and reaching agreements regarding respect for the neutrality of our medical facility and activities. These agreements were grounded in International Humanitarian Law (IHL), which enshrines the right and responsibility to treat all wounded and sick without discrimination; stipulates that wounded combatants who lay down arms should no longer be considered combatants; and provides protection to all patients and medical staff in the facility. MSF affirmed that its strict “no weapons” policy would be enforced at all times within the hospital compound, and the location and GPS coordinates of the hospital were shared repeatedly with all relevant parties.

The Week Before the Airstrikes

When heavy fighting broke out in Kunduz, MSF’s team at the KTC launched a mass casualty plan for wounded patients and later increased the number of beds available to treat them. As is standard practice, MSF teams did not ask which armed group patients belonged to when they arrived at the hospital. Uniforms and other distinctive indicators made it clear, however, that many wounded combatants were among the patients.

Initially, government troops and police made up the bulk of the war-wounded. As the fighting continued, the ratio shifted, and more Taliban fighters were brought in for treatment. From September 28 to October 2, staff treated 376 patients in the ER—more than a quarter were women or children younger than 15—and performed 138 surgeries. The no-weapons policy remained in effect at all times, and MSF again reaffirmed the KTC’s location in emails to the US Department of Defense, Afghanistan’s Ministries of Interior and Defense, and the US army in Kabul.

The Attack

MSF staff said it was calm in and around the hospital on the night of October 2—no fighting, no planes overhead, no combatants observed. The KTC was busy, as medical staff tried to catch up on a backlog of pending surgeries, continuing to work well past midnight. As one of the few buildings in the city with electricity, the KTC was brightly lit, too. There were 105 patients in the hospital; 3 or 4 were wounded government combatants, according to staff estimates, and approximately 20 patients were wounded Taliban. There were 140 Afghan staff members and nine international staff inside the hospital, as well as a delegate from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Between 2:00 a.m. and 2:09 a.m. on October 3, the first in what would be a sustained series of precise airstrikes was launched targeting the main hospital building. The first strike killed two patients on operating tables, among others, and drove staff to seek shelter in the sterilization room. The explosions woke MSF international staff members sleeping in the administrative building, where an MSF nurse arrived covered in debris and blood, his left arm hanging from a small piece of tissue. Medics provided immediate treatment to stabilize him.

Amidst ongoing volleys of fire and a series of ground-shaking explosions, many staff heard something that sounded like a propeller plane circling the hospital—consistent with reports that an American AC-130 gunship carried out the attacks. Many staff described seeing people shot as they ran from the main hospital building. Staff also recounted a patient in a wheelchair killed by shrapnel as he attempted to escape, an MSF doctor getting his leg blown off, people running while on fire before falling to the ground, and a staff member decapitated by shrapnel. Fire also hit the southern area of the compound, where two unarmed MSF guards were later found dead from shrapnel wounds.

Not a single MSF staff member reported the presence of any armed combatants or fighting in or from the hospital compound prior to or during the airstrikes, which finally stopped between one hour and 75 minutes after they began.

At least 30 people were killed in the attack, including 10 patients and 13 staff members; 7 more bodies were burned beyond recognition. Immediately after the airstrikes, MSF’s surviving medical team collected all the supplies they could, converted an administrative room into a makeshift emergency room, triaged patients, and began treating the wounded. Surgeries were performed on an office desk and kitchen table.

MSF contacted the Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) provincial hospital in Kunduz, which sent ambulances to pick up the wounded. Fighting had by now begun outside the hospital compound, and as patients were being transferred, the Afghan Special Forces arrived. Some started searching the MSF and MoPH ambulances for Taliban patients. One ambulance was caught in the crossfire while exiting the KTC. Thankfully, no one was wounded.

All staff members were eventually evacuated. The hospital has remained closed since the attack.

The Aftermath: Calls for Investigation

Since its inception, MSF has spoken out about attacks on medical facilities, personnel, and patients. The particulars of our responses may vary, but the purpose is always the same: protecting our facilities so we can deliver lifesaving care in places where the needs are immense and the options are few. We also aim to promote the principles and existing legal tenets that allow us to do this work.

We tailor our responses to the specific circumstances and details of each incident. In Kunduz, a fully functioning hospital managed and operated solely by MSF was specifically targeted by a party to a conflict, resulting in the largest loss of life of MSF staff since the Rwandan genocide, and the largest ever involving an aerial attack.

The US took responsibility. President Obama himself called Dr. Joanne Liu, our international president, to apologize. He pledged a thorough investigation into what happened. Results were promised within 30 days. But that did not materialize. On November 5, MSF released its own initial review on the attack and shared it with the US and Afghan governments and others.

The week after the attacks, we called for an independent investigation, asking states to mobilize the International Humanitarian Fact-Finding Commission, which was created by the Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions to investigate incidents like this one.

The IHFFC can pursue the matter in a way the US (or any involved party) cannot. As we noted in an October 24 op-ed in The New York Times, the US’s “findings will understandably be rooted in the context of military doctrine and practice, not international humanitarian law. They will examine apparent failures to follow the United States military’s rules of engagement, but they are unlikely to ask whether or not those rules of engagement themselves comport with international standards for the rules of war. We also need to know the degree to which the lines between military and civilian targets have been blurred, so we can better understand the risks our teams in Afghanistan and elsewhere will face.”

An IHFFC investigation, we noted, “could not only review the facts of the Kunduz case; it could also establish a record of the violations of international law that appear to have occurred and set objective precedents of what is and is not tolerable in a conflict.”

The op-ed continued: “Our call for an independent international investigation is not a political gesture, pursued solely because the United States was so prominently involved in the Kunduz attack. Just as our medical ethics and commitment to international humanitarian law mandate that we treat all wounded persons in a conflict zone —regardless of affiliation, race or religion, and regardless of how or why they were injured — our founding principles compel us to highlight encroachments on the medical facilities through which we deliver care…[I]f international humanitarian law is flouted, if violations on this scale can be dismissed as a ‘mistake,’ ‘the fog of war’ or even just ‘a terrible tragedy,’ then all of our medical staff, projects and patients in conflict zones could be jeopardized.”

We received a number of calls asking whether we were pushing the US too hard, or losing sight of the notion of “innocent until proven guilty.” But this is, legally speaking, an issue of conduct and outcome, not intent. “In the case of Kunduz,” we wrote in The New York Times, “it is not our responsibility to prove that the United States military violated the laws of war or its own rules of engagement. It is the responsibility of the party that destroyed a fully functioning hospital, with some 200 staff members and patients inside, to prove that it did not.”

“By consenting to an independent investigation,” we concluded, ““President Obama could reaffirm America’s commitment to international humanitarian law, restore its credibility when it comes to denouncing violations by other states, and help reinforce the protected status of medical facilities in conflict zones.”

In the weeks that followed, more than 500,000 people echoed our call by signing a petition we started (www.change.org/evenwarhasrules) urging the president to assent to the independent investigation.

Attacks Elsewhere

Three weeks after the Kunduz attacks, an MSF-supported hospital in Haydan, in Yemen’s Sa’ada Province, was bombed and destroyed. Numerous hospitals, including some that MSF support, have been bombed in Syria, and medical facilities in other countries have been attacked. There have been questions about why MSF has focused so much attention and called for an independent investigation in the case of Kunduz, but not for other incidents.

The attack on the Haydan hospital, for example, occurred in an area where a Saudi-led coalition is waging an all-out war, bombing a wide range of civilian structures, including schools, markets, residential areas, and hospitals, among other targets. The Haydan hospital was a Ministry of Health facility supported by MSF. We have repeatedly called publicly for answers and accountability for the Haydan attacks, and for many other attacks on civilian targets in Yemen conducted by all parties to the conflict. But given the nature of the hospital, and given the nature of the war, any call for an investigation would have to come from Yemen’s Ministry of Health. And any investigation should not only look at why the Haydan hospital was bombed, but at how the war as a whole is being waged.

This is not solely about whether or not Yemen or Afghanistan are safe for aid workers, however. It’s about how countries fighting wars under the banner of counter-terrorism too often seek to extricate themselves from the bounds of international treaties and conventions. This was part of the post-9/11 rhetoric coming out of the US, when Bush administration officials labeled the Geneva Conventions “quaint,” and it relates to how the US’s drone program, to name one, operates now. This is how Russia conducted itself in Chechnya and elsewhere and is now conducting itself in Syria, where it bombed several medical centers in the first weeks of its overt involvement in the country. This is certainly how the Assad regime directs its campaign against its people.

Some foreign affairs analysts have said that MSF holds states to a different standard than militias and insurgent groups in places like Syria, Central African Republic, South Sudan, and Somalia. It would be false to say that we hold our tongues about atrocities committed by non-state actors. But it is true that states—which pass laws, set policies, and represent their citizens internationally—should operate to a higher standard. It would be extremely disturbing if they or their defenders preferred to be benchmarked against groups like the Seleka, Boko Haram, or ISIS.

We, and organizations like ours, need answers to questions about Haydan, about Kunduz, about the slaughter of medical workers in Syria, and other like instances because we need to know how much assistance we can plausibly provide while also keeping our teams safe. We need to know if the international community is content to tacitly condone the bombing of hospitals and the trampling of the Geneva Conventions. For us, IHL is hardly “quaint.” It is the difference between life and death, of staff, of patients, of populations. And world leaders should be saying the same thing, acting with the same conviction, and demanding the same sort of accountability when they or any other body violate these lifesaving principles.