The Greater Kasai region, in southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), had long been untouched by the conflicts that have scarred much of the country. But in 2016, escalating violence between armed groups turned this peaceful region into one of the most serious humanitarian crises in the world.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) began assisting victims of violence in Kasai in May 2017, in the midst of intense conflict. Teams rehabilitated the trauma wing of the Kananga Provincial Hospital, initially focusing on surgical care for trauma patients and later adapting to treat victims of sexual violence. From May 2017 to September 2018, MSF treated 2,600 victims of sexual violence at the hospital. Eighty percent of these patients reported that they were attacked by armed men. Most of MSF’s patients sought treatment more than a month after they were attacked, making it difficult to know how many other victims there might be.

From May 2017 to September 2018, MSF treated 2,600 victims of sexual violence at the hospital. Eighty percent of these patients reported that they were attacked by armed men. Most of MSF’s patients sought treatment more than a month after they were attacked, making it difficult to know how many other victims there might be.

Victims of rape require medical care within 72 hours of the attack so that they can be protected against HIV and receive emergency contraception, but the majority of patients in Kananga arrive after that window has closed. Nevertheless, they can still benefit from treatment for sexually transmitted diseases, vaccinations, and both group and one-on-one mental health counseling offered by MSF.

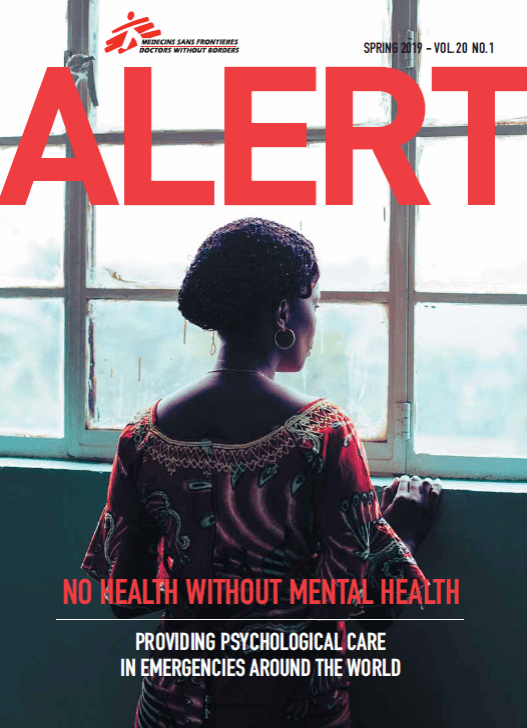

In Kananga, MSF provided psychosocial support and psychological care for more than 200 victims of sexual violence on average each month through individual and group sessions. “I remember as if it was yesterday,” says Bibiche*, recalling the details of the attack against her and her family. “A group of men came into the house, and they destroyed everything—our things, and us. First, they raped my little sister, then my sister-in-law, and me last. At the time, we didn’t speak out about it, or ask for help.”

One year passed before Bibiche heard about the care being provided by MSF for victims of sexual violence. “A female doctor had come to tell us about an organization of doctors here in Kananga that was treating rape survivors, even if the rape went back as far as last year,” says Bibiche. “When I came [here], the doctors all greeted me with a warm smile and I felt really welcome.”

Sexual violence victims see a psychologist when they first arrive at the hospital. “It helps to build trust with the patient and to make them feel comfortable before they have a medical examination,” says Angela Modarelli, MSF mental health manager in Kananga.

Often this is the first time a patient has spoken about what has happened to them, so it is important to create a safe and confidential space for the patient to tell their story.

Mental health treatment differs for each individual and is determined by evaluating the attack’s physical, psychological, and social consequences. Most patients attend three sessions, and more are provided as necessary. “We explain what trauma is, and what anxiety, depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder look like,” says Modarelli. Long-term psychological trauma can trigger psychosomatic pain in various parts of the body, so MSF psychologists look for these symptoms and explain to the patient how mental health care can help. Psychoeducation groups are also incorporated into MSF’s mental health guidelines and provided to families and communities. MSF has begun to incorporate physical therapy into the program due to the violent nature of the attacks.

While the majority of our patients in Kananga were women, 32 were men, some of whom reported having been forced under armed threat to rape members of their own community. Male victims of sexual violence are more likely to stay silent about their attacks, often because of stigma or a fear of being rejected by the community. “Often men will come seeking mental health care, complaining of a lack of sleep, feeling sad and depressed, or having suicidal thoughts,” says Fagard-Sultan. “But after a few sessions with a psychologist, they disclose that they were victims of sexual violence.”

“When I sleep I remember everything that happened,” says Pitchou*, who says he was captured by an armed group, tortured, and forced to commit atrocities. After several sessions talking to a psychologist he started to notice some changes. “Even if I’m not fully well yet, I feel that I’m on the way to something better.” In addition to individual counseling, MSF holds group sessions in Kananga to allow people to share their stories with others who have experienced similar trauma. “Our main goal for support group sessions is to offer comfort and connectedness to others,” says Modarelli. “By facilitating exchanges between people who share similar experiences, these sessions help to reduce stress and break down feelings of isolation. We reinforce the strengths and share them within the group, so people do not feel alone in what they have lived.”

*patient names have been changed.