An interview with MSF nurse Clara Delacre

MSF nurse Clara Delacre recently returned from northeastern Uganda, where she had been working in a nutritional program in Kaabong district, Karamoja region. Here, she talks about the program and about how MSF responds to malnutrition.

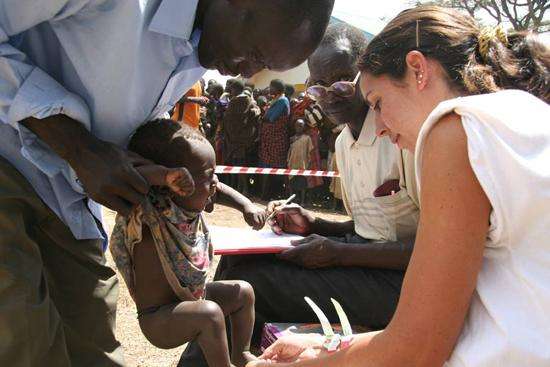

Uganda 2008 © Miquel Sitjar/MSF

MSF nurse Clara Delacre examines a child for malnourishment in Karamoja.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) nurse Clara Delacre recently returned from northeastern Uganda, where she had been working in a nutritional program in Kaabong district, Karamoja region. Here, she talks about the program and about how MSF responds to malnutrition.

When did MSF start working in Karamoja?

In March 2007, the World Food Program conducted a nutritional survey in the area and the results revealed a very high malnutrition rate. At that time, MSF was already running several regular projects in the country and decided to go and work in the Karamoja region in June 2007.

MSF conducted another nutritional survey in November 2007 and also a retrospective mortality survey; in both cases the resulting rates were very high. The nutritional program was implemented based on these data. This program currently also includes support to the pediatric hospital and to several health centers.

In Karamoja, we are working in the Kaabong district, which encompasses nine sub-districts and we are covering all of them. Since we started working in this district we have treated over 4,500 malnourished children. While we were working in Kaabong we learned that there was also malnutrition further south in Moroto and Nakapiripirit district and we decided to carry out a rapid assessment, which showed very high rates of child malnutrition, particularly severe malnutrition. Now, MSF is also working on nutrition in Moroto.

When and how does MSF implement a nutritional program?

Usually, an organization sounds the alarm, or if you are working in the area you see it for yourself, and you can monitor it. During the assessment process, the involvement of community leaders and health centers is a must. We inform them in advance we are going to visit their area. They help us to mobilize the mothers so that they come with their children under 5 and older than 6 months. The first thing we do is conduct a rapid assessment through MUAC (middle-upper arm circumference), a bracelet that enables us to know rapidly whether a child is malnourished or not. Depending on the results of this assessment, we will decide whether to launch an intervention or not.

Malnourished children or those at risk are weighed and measured and they are diagnosed for malnutrition. Those who are malnourished are admitted to the program. While we treat patients, we keep actively tracing new cases and screening. When the number of patients in the program decreases, then the team is reduced, while still monitoring the situation.

What is the strategy MSF is following to treat malnourished children?

In the past, MSF admitted all severely malnourished children. Now both severely and moderately malnourished are treated as outpatients and only those suffering from medical complications and fulfilling admission criteria are hospitalized. For example, if a severely malnourished child cannot eat or needs to be fed milk through a nasogastric tube, the child is admitted until outpatient treatment can be provided. Sometimes, moderately malnourished children get sick; for instance, they get severe malaria and need to be admitted to the stabilization center where they are treated for the disease while still being provided the nutritional treatment.

We run a stabilization center at the Kaabong hospital, which includes a pediatrics department, where all malnourished children suffering from medical complications in the district are referred to.

In Karamoja you are using ready-to-use therapeutic food or RUF. What are the advantages of this treatment in the field?

A 500-calorie serving of vitamin- and nutrient-rich RUF meets all a child's needs. Fortified blended flours only cover part of the needs. Logistically, it is much simpler to use, and it is better medically, too.

Blended flours are much more difficult to manage. When you use these flours, the calories a child needs daily are calculated and then you prepare them, give the mother the right amount of flour and explain to her that she needs to mix it with half a cup of hot water and then give the child the mixture three times a day in order to provide the nutritional supplement the child needs. In many places where MSF works, getting clean water to prepare these flours is very complicated and the child can get sick when drinking contaminated water.

How has the population responded to the MSF project?

When we started the program, the number of absentees (patients who do not show up to their follow-up appointments) or defaulters (those who never come back and cannot be traced) was very high. Part of the population is semi-nomadic, so following up with them is no easy task. Others are not aware that their child is sick. Many times they come for food and then you try to explain to them that their baby is malnourished and that it is not growing properly so if it gets sick it may die. But we have worked a lot to avoid absenteeism and defaulting and made a great effort to ensure all the children in the program go through it until completion and the situation has improved quite a lot.

We have also introduced “support and discharge rations”. When patients recover they are given food for a month for the entire family. In this way we ensure that at least during a month children eat well and then since the program goes on if there are any problems the children come back.

After one year working in Karamoja, what is the situation like?

Currently, the number of children admitted is decreasing. In addition, the World Food Program has carried out another nutritional survey revealing global malnutrition rates at 9 percent compared to 15 percent in the last survey.

We can really say that the result of what we are doing is showing a little. However, the hunger gap—the period between the planting and harvesting of crops when food reserves are typically scarce—is starting now, and the situation may worsen.

In Karamoja, malnutrition is cyclical and chronic. Part of the population is nomadic and is not used to planting. Besides, there are many desert areas. For example, the latest rains have come late by about three months, so there is no harvest. Now they are only planting peanuts and sorghum but these crops will not last long; nutritional crises are starting anew. You can see that children suffer from chronic malnutrition because of their stunted growth; a one-year old child can weigh and measure as little as a two-month old baby.