Skip to: Chad | Chechnya | Burundi | Colombia | DR Congo | Malaria | Somalia | China | Access to Medicines | Ivory Coast

Mother with child lines up to be registered at the MSF health unit in the refugee camp of Tiné Chad. Photo © Dieter Telemans

Far beyond the headlines, two of the world's most violent conflicts raged on Chad's borders in 2003. Tens of thousands of people were uprooted by brutal wars in neighboring Central African Republic (CAR) and Sudan and fled for their lives to this impoverished central African nation. From January to March, more than 40,000 people found refuge in southern Chad, especially in Goré, Maro, and Ndanamadji, when a coup in CAR plunged the area into chaos. Then in July, fighting in the Darfur region of Sudan forced more than 95,000 people to seek safety in the barren border regions of eastern Chad. These refugees fled with little or no possessions when their villages came under fire from helicopters and local militias. Many of those who reached Chad describe seeing their villages and crops burned to the ground. Assistance and protection has been slow in coming and inadequate as only a handful of aid agencies have provided sustained meaningful aid.

Frequently portrayed by Russia as its own "war on terrorism," the Chechen conflict continued to take a heavy toll on civilians in the North Caucasus in 2003. The war in Chechnya still rages, and reports of violence, arbitrary arrest, and disappearances are common. Throughout the year, nearly 200,000 displaced people living in tent camps and makeshift shelters in Chechnya and the neighboring Russian republics of Dagestan and Ingushetia have been victims of a concerted campaign of harassment and coercion aimed at pressing them to return to war-torn Chechnya. Authorities closed several camps in Ingushetia alone during 2003, and nearly 30,000 displaced were pushed back into a war zone. As a result, only 8,500 people live in tent camps today. In February 98 percent of nearly 3,000 families interviewed by MSF said they feared for their lives if they had to go back to Chechnya. Even so, the pressure continues. Officials claim that no one is being forced to return, but authorities block groups from providing alternative shelters and impose additional bureaucratic restrictions on aid organizations, significantly limiting their ability to improve the living conditions of the displaced Chechens. The extreme violence against civilians has extended to international aid workers, as well, with MSF Head of Mission Arjan Erkel still held hostage more than 500 days since he was kidnapped in Dagestan on August 12, 2002. This increase in security threats and violence has made effective independent humanitarian aid nearly impossible in Chechnya at a time when civilian needs are at their greatest.

At this health center run by MSF in the Kamengue district, people with cholera and malaria are treated as well as those wounded by war. Some 40% of those wounded by war are women and children. Photo © Ian Berry/Magnum Photos

During ten years of civil war, Burundi's civilians have been subject to systematic and unrelenting violence. The life expectancy has plummeted from 60 to 40, and nearly 300,000 Burundians have been killed. In the two years since a power-sharing agreement lifted hopes, the war grinds on in Burundi's cities and countryside. With only one physician for every 100,000 people (one of the worst ratios in the world), the violence and lack of medical services have left the vast majority of people with no access to health care. Where rebel groups and government forces are at war, violence against civilians, including rape by armed combatants, is a daily occurrence. Governments in the neighboring countries hosting the 790,000 Burundian refugees are pressuring the refugees to return home, yet resettlement programs managed by international agencies are poorly organized and underfunded. In the capital, Bujumbura, the veneer of calm provided by the peace process was shattered in July 2003 when the Forces for National Liberation (FNL), the only rebel group that refused to join the power-sharing agreement, relentlessly shelled the city. The ten-day attack claimed hundreds of lives and forced tens of thousands to flee their homes. Since then, and despite a recent breakthrough in talks between the government and the main rebel group, attacks on civilians continue in the capital and rural areas, underlining the grim truth that in this country supposedly at peace, no one is safe.

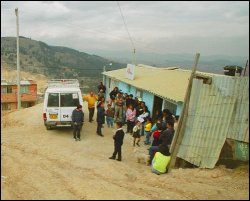

An MSF mobile clinic providing basic health care in impoverished rural areas of Colombia. Each day, entire families arrive on foot or by horse from homes often several hours away. Photo © Juan Carlos Tomasi

The chronic conflict in Colombia has almost become invisible to the outside world. But the effects on Colombians are all too evident. Unofficial estimates put the number of displaced people at three million, many of whom live in precarious conditions without water, electricity, or other basic services in burgeoning shantytowns on the outskirts of major cities where pressure from armed groups continues. Land conflict, crop fumigations in the "war on drugs", and constant threats from paramilitary forces, government soldiers, and guerrillas displace more and more people each day, while overcrowding and acute poverty increase their exposure to health problems, sexual abuse, and exploitation. Colombia's urban centers are also plagued by a more generalized violence, which exacerbates structural inequities that exclude the poorest and the displaced from access to health care. Those who have not fled their homes try to eke out an existence in the isolated, conflict-scarred countryside. In these increasingly insecure rural areas, people find themselves cut-off from even basic health care services and more vulnerable to treatable diseases and chronic malnutrition.

Twenty years of neglect and near-continuous war in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have claimed the lives of millions and left the essential services of the country in ruin. In the last five years alone, some groups estimate that three million people have died in this country the size of Western Europe -mostly from disease and famine indirectly caused by the conflict. While the carnage in the eastern DRC, especially in the northeastern city of Bunia, received a fair amount of media attention this past spring, the relentless terror endured by tens of thousands of people in the surrounding areas barely registered. In these regions, rival armed groups backed by foreign interests vied for power in a war that inflamed local tensions and destabilized the country, mainly through organized violence against civilians. People trapped in this massive human catastrophe speak of a nearly unimaginable scale of suffering, with massacres, rape, assault, and looting separating families and displacing large numbers of people. Away from the daily terror and intense conflict in Ituri and other troubled areas of eastern DRC, malnutrition, disease, and the near-total absence of basic health care continue to claim thousands of lives in the rest of the country.

Each year, malaria claims between 1-2 million lives, mainly children in Africa. In fact, a child in Africa dies from malaria every 30 seconds, nearly 3,000 every day. Resistance has rendered chloroquine useless and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) increasingly ineffective. An effective alternative treatment exists, though: artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) combines artemisinin, an extract from the Chinese plant Artemisia annua, with other antimalarials to minimize the chance of resistance. Most health professionals and malaria experts agree that ACT is the best option for treating malaria today, and the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended the treatment since 2001 especially during epidemics. Cost is the most cited reason given for why ACT is not available to the children who are dying from malaria daily. Today, ACT can cost as little as $1 per treatment, and if ACT were introduced more widely, the cost would certainly decrease. Still, international donors and governments continue buying chloroquine and SP, and offer dying patients medicines they know do not work.

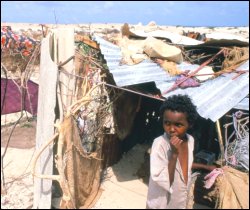

Child in front of a shelter made of cloth and metal plates in an IDP camp in Somalia. Photo © Wim Van Cappellen

For more than twelve years, civilians in Somalia have been punished by cycles of violence, displacement, drought, and flooding. With no recognized central government, these factors have brought agricultural development to a standstill, perpetuated extreme poverty, and forced millions of Somalis into a hand-to-mouth form of survival. Of more than 800,000 people who fled Somalia in 1991 and 1992, during the heart of the crisis that began the nation's downward spiral, almost half are still living as refugees in surrounding countries. Inside Somalia, up to 450,000 people remain displaced, with 150,000 scraping together an unstable existence in camps in the capital Mogadishu. Civilians are still routinely caught in frequent armed clashes between the myriad of clan-based militias that remain active throughout much of the country. With no working government and little outside support, the already poor health care system has ceased to function in many areas. This has hit women's health especially hard: more women die in childbirth in Somalia than almost anywhere else on earth. Low vaccination coverage and inadequate sanitary conditions result in frequent cholera and measles outbreaks in the country. Rarely is there anyone there to provide assistance. Persistent violence and a lack of international funding have hindered aid agencies from mounting an effective response to the immense needs in the country.

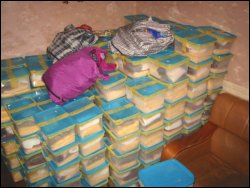

200 food kits prepared to be given to North Korean refugees forced to return to North Korea. They include oil, rice, sugar, soap, red beans and corn. Photo © MSF

Political repression and chronic food shortages have forced thousands of North Koreans to risk arrest and severe reprisals in order to seek safety and means of survival in China. North Koreans are chased by Chinese authorities who consider them illegal migrants, and many cannot even reach the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) office to apply for asylum. North Koreans in China live in hiding, constantly under the threat of forced return to North Korea where they face brutal reprisals ranging from detention in re-education camps to execution. Seeking asylum and providing assistance to North Koreans are considered criminal offenses in China. As this repression has intensified since 2001, thousands of refugees have been forced back to North Korea, and international and national aid workers alike have been sent to Chinese jails. Still, starving North Koreans continue to cross the border in a desperate search for a better life. The UNHCR remains passive with regard to promoting the rights of North Korean refugees in China and holding China accountable to the international refugee conventions it has signed.

A woman in need of ARV therapy in Guatepeque who lives with a disabled sister and her little son in Guatemala. Photo © Juan Carlos Tomasi

"It's already hard enough to get treatment here," said Carmen, a soft-spoken Guatemalan woman in her 60s. "Why wouldn't the United States want to help us in this? They should not make it harder." Carmen is one of the nearly two million people living with HIV or AIDS in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one of the six million people throughout the world who are in urgent clinical need of antiretroviral therapy (ARV). But the US and its powerful pharmaceutical industry have made it harder by pushing for more stringent intellectual property requirements in regional trade agreements like the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA) and the US-Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) that restrict generic competition, the only factor that has resulted in sustainable price reductions for essential medicines. Such provisions undermine the 2001 Doha Declaration, an agreement adopted by all World Trade Organization (WTO) members which reaffirmed the right of countries to make full use of existing flexibilities in international trade treaties in order to "protect public health and promote access to medicines for all." Similar agreements pursued by the US with Morocco, Thailand, five southern African states, and other countries will most likely include similar restrictions. These proposals threaten to trade away the lives of millions for commercial profit and make lifesaving treatment a luxury few people like Carmen can afford.

Young woman with amputated leg, one of many civilian victims of the war. The hospital in Man is the only hospital in this region of Ivory Coast where surgical interventions can be done. Photo © Peter Casaer/MSF

Civil war broke out in Ivory Coast in September 2002 causing displacement and a breakdown in health services, especially in the western regions of this West African nation. Civilians living in the war zones were exposed to extreme violence inflicted upon them by the various warring parties and conflicts between locals and outsiders over land ownership drove yet more people from their homes. Health workers fled the war zones and medical facilities in rebel-held areas were looted and cut off from supplies, dramatically reducing access to health care at a time when it was most needed by civilians. Displacement, violence, and lack of medical care led to increased malnutrition and the outbreak of preventable illnesses throughout the north and west of the country. Only a few years earlier, Ivory Coast had been the most prosperous and peaceful nation in West Africa. In 2003, civilians in the west of the country watched their homes and their villages subjected to bombardment from helicopter gunships and looting from marauding militias. Violence spilling over from the war in neighboring Liberia, coupled with flaring ethnic tensions in western Ivory Coast, pushed even more people away from whatever health care was provided. Over a year after the coup, fighting has subsided, but the country remains divided, many people are still displaced, access to health care remains difficult, and the peace remains fragile.