Dr. Marcus Bergman, part of MSF's team in Pinga, in DRC's North Kivu province, relates a harrowing episode that occurred shortly before worsening insecurity forced MSF to suspend its programs in the area.

DRC 2013 © MSF

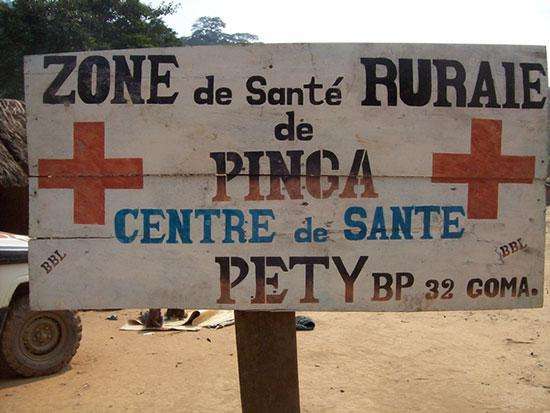

The sign outside MSF's facility in Pinga, North Kivu province.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was recently forced to suspend its medical activities in and around the town of Pinga, in Democratic Republic of Congo’s North Kivu province, amid worsening insecurity and threats to humanitarian workers. Dr. Marcus Bergman had been working for MSF in Pinga since February 2013, as part of the team providing medical care to people affected by the longstanding and often unpredictable conflict in the area.

Here, he relates a particularly terrifying episode that occurred shortly before programs were suspended.

At midday, we heard the sound of a gunshot nearby. At first we thought it was a stray bullet, perhaps a drunken child soldier since it was an unusual time of day for an attack to take place. Armed militias usually attack under cover of darkness, either just before dawn or at dusk after the sun has set. But then we heard the sound again. And again. We knew then fighting had begun.

I was in a staff meeting at the hospital in Pinga, located just opposite our base. For a second, I thought about running to the base to take cover, but then realized that it was too late. We had to shelter in the hospital together with patients and staff. In panic, people ran towards the meeting room, but we then decided to move to the room behind it. Crouching down, we moved pressed against the wall.

Patients who had just had surgery, sick people, elderly people, children and hospital staff were all seated together in a room far too small for the number of people in it. I sat on the floor behind a sack of flour with a little boy in my arms. I tried to get as close to the floor as I could to avoid any stray bullets. The boy was playing with my fingers while I desperately held onto him.

I heard the shooting coming closer and closer. We realized the men were just outside. People were shaking and crying but everyone remained silent. I felt my heart beating against the boy's back. I have never felt so scared before. It was dark. The door was shut and there was a curtain pulled across the window. The air was sticky. With the volume turned down on my radio, I whispered a frantic call to base to tell them the men were in the hospital.

Suddenly we heard the men enter the room next door. We heard people on the other side of the wall crying out that they were civilians. I held my breath, utterly terrified, waiting to hear their executions. Silhouettes appeared outside our window and we heard talking. We sat silently. Then a baby started crying and people started desperately hushing it.

Gun shots continued to echo. The baby’s cries triggered more crying from other children in the room. But for some reason the door to our room was never opened. After about 40 minutes, a Congolese doctor entered and told us that the attackers had retreated. The people in the room next to us had been spared. A man with a machete had burst in but turned back when he saw that there were only civilians there.

We waited until we could no longer hear gunfire before leaving the room. We then realized that not all of us had been fortunate. A woman collapsed on the ground, screaming. The baby she carried on her back had been hit by a stray bullet. The bullet had entered under the baby’s nose and exited through the back of the head. The little girl had died immediately. She looked as if she was asleep. But her body was already cold.