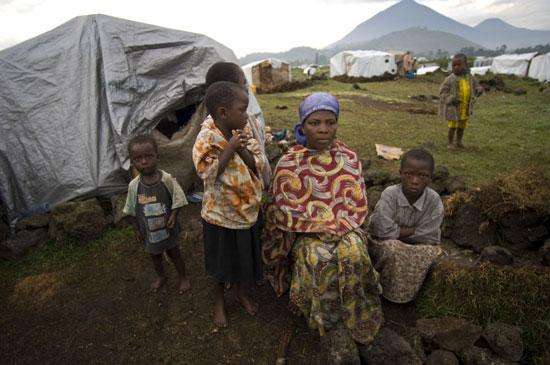

A displaced family from DRC sits outside their tent made of plastic sheeting.

Uganda 2007 ©Vanessa Vick/MSF

When fighting erupted between armed groups and government forces in the North Kivu

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) helped set up a transit site in Nyakabanda, situated about 10 miles from the DRC border in

Here, Cobey describes how MSF teams monitored and responded to this emergency refugee influx.

Approaching a new emergency

“You can put up an MSF tent in 10 minutes and start seeing patients as long as you have your drugs.”

MSF has ongoing projects in northern Uganda and, on the other side of the border in Democratic Republic of Congo, an MSF team was providing services in Rutshuru, North Kivu. The team in DRC had used mobile clinics to reach the people who have been caught up in the armed conflict there and repeatedly displaced from their homes. Before I left New York for my assignment, a frontline of heavy fighting cut the DRC team off from a segment of this population. So they asked the MSF team in Uganda to reach these refugees from the Ugandan side of the border.

MSF assembled a team with one nurse, one logistician, and the head of mission, who is also a logistician. What always strikes me about MSF is that everybody, even at the senior level of management, can be all-hands-on-deck in an emergency. This new team ran several mobile clinics from Uganda, to access the population that had been forced out of the DRC project’s reach.

The team was already thinking along two different lines of intervention, depending on what would happen on the ground. Plan A was that MSF would continue doing mobile clinics based in Uganda to reach the Congolese population. Plan B existed in case something happened to cause large numbers of people to flee into Uganda, and it meant that we would have to intervene in a refugee transit site. Plan B came into effect when I was in the air, on my way to the project. That day, heavy fighting caused thousands of people to cross the border into Uganda.

The logistics coordinator, who’s normally based in Kampala, had just gotten back from vacation the same night that I arrived. He was told, “Tomorrow morning you’re driving to Kisoro with Laura because we’ll now be working at a refugee transit site and need more logisticians.” So the team started with him, a doctor, a nurse, two logisticians, the head of mission who had been functioning as field coordinator, and me. I was there as the field coordinator, but I’m also a nurse.

Nyakabanda transit site opens

Here patients are registered before seeing a doctor or nurse at the MSF clinic.

Uganda 2007 ©Vanessa Vick

The immediate needs were for shelter, water, sanitation, and food. We set up the tents and worked directly with the district authorities to set up the water distribution system, actually installing the tanks and pipes. We had to make a gravity-fed system by digging through volcanic rock, which is very difficult, and then essentially making mountains so that the water tanks could sit on top and drain. Digging latrines was another intervention that had to happen immediately. The number of refugees grew quickly. We went from 2,000 to 3,000, and the next day we counted 6,000, and after two weeks we’d reached 11,000. You immediately need to build enough latrines and maintain them because poor sanitation can be a huge disease risk.

I don’t even remember the clinic going up just because it happened so quickly. We had some tents and skeleton structures from back in August, when MSF had done an assessment in response to the first movements of people back and forth across the border. You can put up an MSF tent in 10 minutes and start seeing patients as long as you have your drugs. As the camp grew and as our consultations increased, we needed to expand the clinic. But again, because we had logisticians right there, we could just say that we need this waiting room or this dressing room built. It gets built in literally an hour and then we start using it.

Living in Nyakabanda

“Imagine on a cold day having to sleep directly on the cement with just a piece of plastic on top of you and maybe a blanket.”

The refugees were living under plastic sheeting. At an altitude of over 7,000 feet above sea level, the climate there is cold, dropping to the 50s at night, and it’s also rainy. The ground is very cold and people don’t have shoes. So imagine on a cold day having to sleep directly on the cement with just a piece of plastic on top of you and maybe a blanket.

Non-food items were distributed very slowly. And no matter how much refugees get in terms of distribution, it’s never comfortable to live crowded in one place under a piece of plastic, directly on the ground. In one shelter, I counted up to 10 people. Families lived together, but people hosted other families too.

Having been unfortunately displaced numerous times, this group of refugees had developed coping mechanisms. Some people might imagine that the refugees we assist are helpless, but what I’ve consistently seen is that they do as much as they can to help each other and to support themselves. When they are fleeing their town in

Typical day for the team

A 70-year-old man managed to bring his sewing machine and continues to work as a tailor despite being displaced.

Uganda 2007 © Vanessa Vick

On a typical day, we’d wake up around 6 a.m., be on the road to the camp around 7:15 a.m., and start seeing patients at 8 a.m. The logistics team would usually reach the site earlier because they needed to start installing pipes, trucking water, and digging latrines. The medical team arrived to triage patients, and seeing patients occupied the bulk of our day. Once things stabilized, consultations could range from 100 to 150 per day. The main medical condition we saw was upper respiratory infection in young children. With young children, that’s much more dangerous than just a simple cold or flu, especially when people aren’t getting adequate nutrition, don’t have the ability to stay warm, and don’t have adequate hygiene. In babies it can develop into pneumonia, which can be lethal. The other main morbidity we saw was diarrheas, which are common in settings that lack adequate hygiene.

At the end of the day we’d usually have team meetings with the national staff, who were all refugees themselves. We also had an outreach team monitoring the health of people in the camp. They walk around with MUAC [middle upper arm circumference] bracelets so they can screen children for malnutrition. They often escort people to the clinic if necessary, or they refer them if they have any suspicion that something’s wrong. After patients were seen in the clinic, the outreach worker would make regular home visits to those needing follow-up. At the end of the day, the outreach workers would tell us what’s happening around the site, whether there are certain areas that need more latrines, or whether there are certain areas where people need to walk too far to get water. After the discussion, we’d probably get home by about 7 p.m.

Nyakabanda transit site closes

The MSF team in DRC was able to restart mobile clinics from their side of the border, to monitor for outbreaks of disease. Often in these situations, part of the justification for us to be somewhere doing mobile clinics or providing health care is that we want to have our finger on the pulse if there is some sort of outbreak. We’re keeping an eye on the health of the population even though they have moved out of the camp. It was a very quick open and close for that project.