When the massacres started in Rwanda twenty-five years ago, on April 7, 1994, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières teams suddenly found themselves caught in a frenzy of violence. MSF, which had teams across the country, was keenly aware of mounting tensions throughout the early 1990s between members of the Hutu ethnic majority—who controlled Rwanda’s government—and the Tutsi minority. But no one was prepared for the scale of the violence to come, as the Hutu-led government launched a calculated plan to exterminate the Tutsis.

Over the 100 days of the genocide, as many as 800,000 Tutsi men, women, and children were massacred at the direction of the Hutu-led government; thousands of Twa people and numerous Hutus who opposed the violent campaign were also killed.

MSF teams bore witness to the slaughter and struggled to provide emergency medical care in an atmosphere of intense violence and fear. As the genocide unfolded—and the international community stood by—MSF grappled with ethical humanitarian dilemmas that still shape the organization’s work today.

No peace

In October 1990, civil war broke out between the Rwandan Armed Forces (RAF), supporting the Hutu-led government of President Juvénal Habyarimana, and the Tutsi-backed Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) forces, comprising Tutsis born in exile and based in neighboring Uganda. The RPF crossed the border into Rwanda from the north, seeking to overthrow Habyarimana’s government.

The Rwandan government and RAF halted the attack, but only narrowly avoided defeat. Peace talks were initiated to broker the sharing of power and facilitate the return of exiled Rwandans, leading to Arusha Accords signed in 1993. But the peace agreement never came into effect. On April 6, 1994, a plane transporting Rwandan president Habyarimana was shot down during its descent to Kigali, Rwanda’s capital.

This president's assassination ended the peace accords and sparked years of strife and horrific violence.

Caught in the middle of a genocide

MSF first began working in Rwanda in 1982. When the massacres started, MSF teams were active in nearly all Rwandan prefectures. From 1994 to 1997, these teams were faced with a succession of unprecedented situations as they struggled to provide emergency medical care in the midst of extreme and unchecked violence. During these years, nearly 200 Rwandan MSF staff members were murdered, in some cases in front of their colleagues.

Frequently confined to their homes for security reasons from April 7 on, MSF teams bore witness to the violence perpetrated against the Tutsi population. When staff members attempted to help their neighbors, militiamen threatened them and ordered Tutsis to turn themselves in. In the town of Murambi, for example, some 12 miles from Kigali, militiamen armed with clubs and machetes murdered a man in front of several Rwandan MSF staff members.

MSF attempted to evacuate its teams from the country, but the Rwandan army refused to allow Tutsi staff to leave. MSF facilities were attacked and looted. Across the country, our teams were separated by ethnicity and in some cases forced to take part in the slaughter. In Butare prefecture’s camps for Burundian refugees, militia members forced Hutu MSF staff to execute Tutsi colleagues. Threatened with death themselves, they felt they had no choice but to obey.

By April 11, when MSF teams were finally airlifted out, thousands of people had already been executed. Confined to Kigali and Butare prefecture, details about what was unfolding in the rest of the country were sparse. However, Rwandan refugees streaming into neighboring countries described targeted, wholesale slaughter.

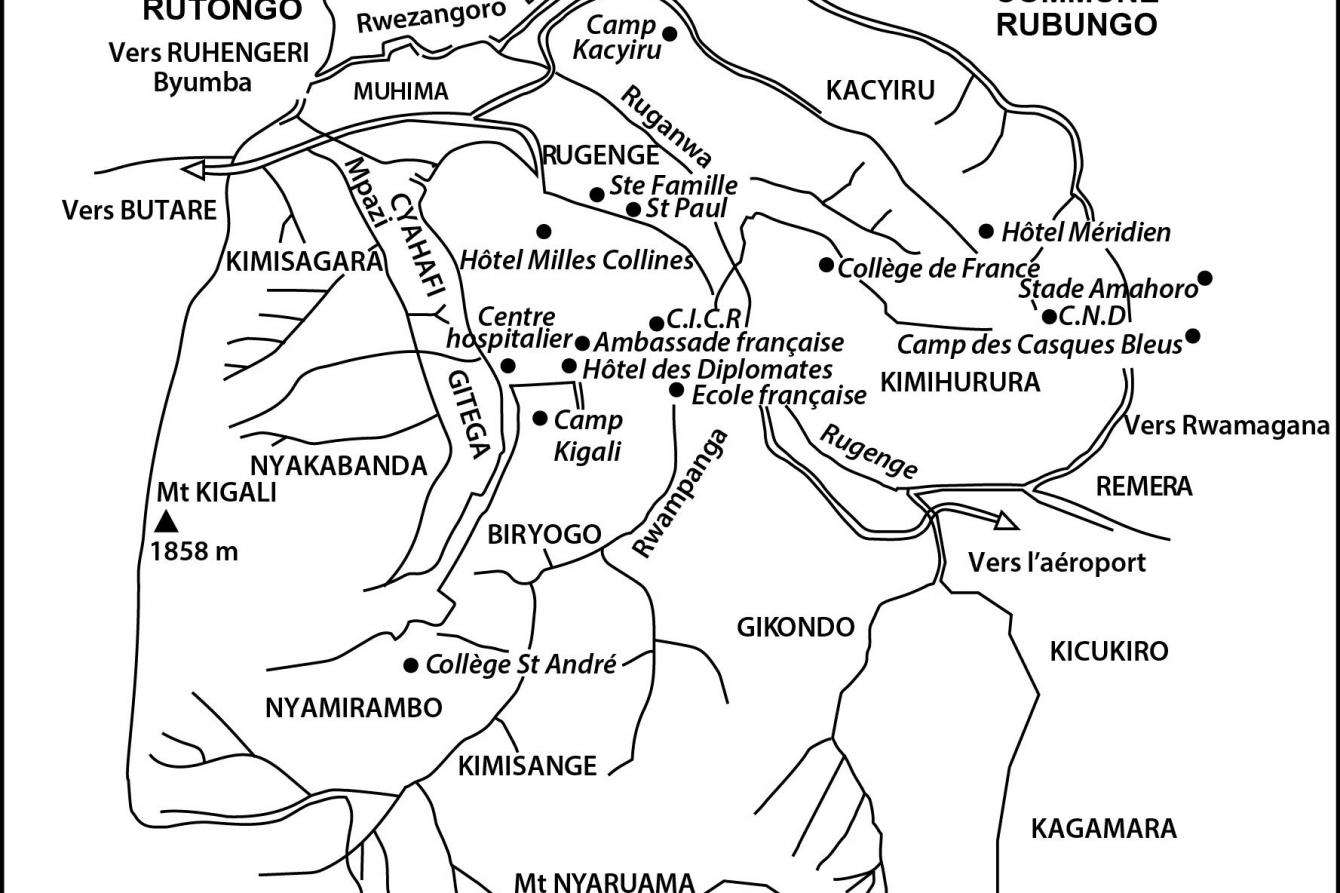

On April 14, a team of experienced MSF volunteers returned from neighboring Burundi to the Rwandan capital to set up a surgical program. University Central Hospital of Kigali, which should have been used for treating the wounded, had instead become a slaughterhouse where the perpetrators of the genocide went to execute patients. The decision was made to open a field hospital under the coordination of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

Teams set about transporting patients in need of surgery to this field hospital and providing medical treatment where people in danger had taken refuge. But these places—orphanages, schools, religious institutions—were routinely attacked by so-called génocidaires who murdered the able-bodied and finished off the wounded, often soon after MSF’s medical teams had left.

Nearby houses were soon added to the field hospital, which became a place of refuge where those who succeeded in reaching it were able to recuperate in relative safety. However, as soldiers and militiamen searched ambulances, it was all but impossible to safely transport male Tutsi patients. Even the safe passage of Tutsi women and children required endless and grueling negotiation.

For several weeks, our teams assessed the prospects and risks associated with transporting the wounded on a case-by-case basis. They continued treating injured patients in Kigali and did what they could to shelter hundreds of people in their field hospital—all the while encircled by a raging genocide.

Breaking the silence

Initially, the ICRC led public communications about what was transpiring in Rwanda. The ICRC dropped its customary reserve—based on the principle of neutrality to which international humanitarian aid organizations adhere—and condemned “a systematic slaughter” in Rwanda. They stopped short of using the term “genocide.” That loaded word, first mentioned in internal MSF discussions on April 13, came to be used more explicitly after massacres in Butare ten days later left little doubt about the nature of the violence. Rwanda’s Tutsi people were being systematically exterminated.

Although MSF denounced genocide in its communications, there was widespread disagreement within the organization about what should be done to stop it. Was intervention by the international community desirable? What would it achieve? One thing was clear: our primary concern was ensuring the safety of Tutsi people and those who opposed their slaughter. With that in mind, MSF staff set about ensuring that the organization’s medical humanitarian voice was heard.

On May 16, MSF’s operations manager in Kigali returned to Paris. He criticized France’s government on a prominent French television station and questioned its complicity in the events unfolding in Rwanda. However, a meeting held three days later with the directors of the French Presidency’s “Africa Uni” yielded no results. The French government was not prepared to exert pressure on its Rwandan allies to put a stop to the killings.

An op-ed published in The New York Times on May 23 calling on the UN Security Council to intervene was met with a similar response. In reality, too few UN peacekeeping forces were deployed in Rwanda, and they did not have the necessary mandate to influence the course of events. On April 21, their numbers had been reduced to just 270 men, nowhere near enough to ensure the security of humanitarian operations to assist the wounded. The UN Secretary-General’s appeals for military intervention also went unheeded.

After a month of public statements calling for answers with no concrete response from the international community, MSF held a press conference to publicly call for UN intervention. The organization was unambiguous about its demand for the deployment of military troops to Rwanda.

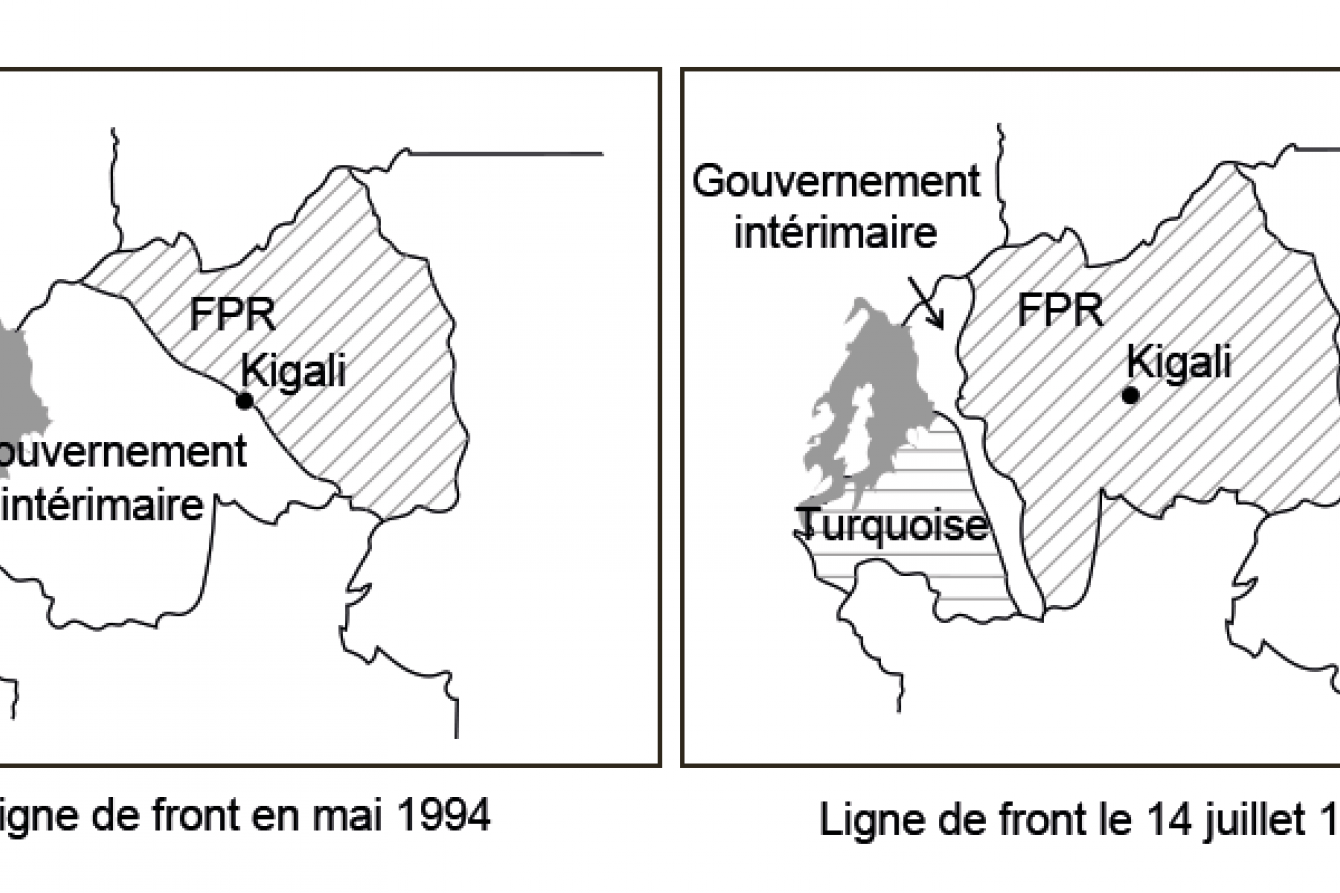

On June 18, 1994, with the support of Senegal, France finally launched a military operation in Rwanda. Under Operation Turquoise, troops deployed to Rwanda gradually took control of the southwest of the country. At the same time, the RPF seized the northwest, and the interim government formed after Habyarimana’s death was defeated. The perpetrators of the genocide were losing the war, but France’s military intervention pushed them into neighboring Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo, or DRC), where they assumed control of the swelling refugee camps.

Rwandan refugee camps in Zaire

As early as July 1994, hundreds of thousands of refugees began fleeing Rwanda out of fear of reprisals or because they had been threatened by the genocidal authorities. In Zaire, refugees congregated close to the border and in the towns of Goma, Bukavu, and Katale in North and South Kivu. Humanitarian aid operations were launched to respond to the massive needs of these vulnerable people, including by MSF, whose teams were already present in all of the countries bordering Rwanda. But among the displaced—three-quarters of whom were women and children—were individuals responsible for the genocide: soldiers and militiamen, some of whom were heavily armed.

MSF teams described the medical, health, and nutrition situation in the refugee camps as catastrophic. Epidemics of cholera, dysentery, and meningitis ravaged the camps—and almost 50,000 people died in the first month after their arrival. On some days, MSF’s cholera treatment centers saw more than 1,000 admissions. In response, our teams implemented vaccination campaigns; outfitted hospitals; conducted health surveys; and distributed dry rations to children under five years old, among whom the rate of acute malnutrition frequently rose above 21 percent.

MSF undertook this emergency response amid growing tensions. The teams had to plan operations on a case-by-case basis according to the needs of the refugees and the threats posed by the presence of soldiers from the former Rwandan army and the militiamen who wielded power in the camps. Civilians regularly suffered acts of violence at the hands of these groups, and security incidents became more and more common, with our teams frequently made the targets of threats fueled by unfounded rumors and propaganda campaigns.

Meanwhile, humanitarian aid was also being massively misappropriated by extremist leaders, denying services to many refugees in need. For example, MSF estimated that almost one-quarter of the refugees in Katale Camp were receiving insufficient food rations because of misappropriation.

These circumstances raised difficult questions for MSF operations managers and teams working in the camps. Humanitarian aid was not reaching the most vulnerable, and MSF was unintentionally supporting a militarized system run by perpetrators of genocide. Was the intervention doing more harm than good? There were no easy answers. With no better option to halt the instrumentalization of humanitarian aid, MSF made the difficult decision to begin pulling out of the Zaire camps in November 1994.

Hunting down and slaughtering the refugees

As the refugee crisis dragged on, the Zaire camps came to serve as a rear base for the genocidal soldiers and militiamen to regroup and launch deadly attacks against civilians across the border in Rwanda. Tensions rose between Rwandan-speaking communities—some of them long-established in Zaire—and resulted in a rapid succession of attacks and counter-attacks. At the same time, the Alliance of Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Congo-Zaire (AFDL), led by Congolese revolutionary Laurent-Désiré Kabila, was formed. The AFDL joined forces with the Rwandan Patriotic Front to launch a territorial conquest from the east of the country.

By October 1996, this rebel group already controlled part of South Kivu and was providing support to the armies of Rwanda and Burundi to attack Rwandan refugee camps. During the following weeks the political and military situation changed radically in North and South Kivu. One after another, towns across the region fell and around 40 refugee camps in Goma, Bukavu, and Uvira were attacked and looted. Hundreds of thousands of refugees fled once more to escape the fighting and slaughter, some to the interior of Zaire and others to Rwanda. In response to the chaos, MSF pulled its teams out of Zaire and sent them across the border to Rwanda.

At the beginning of November, MSF launched a public appeal calling for the creation of a “safe zone” for refugees and intervention by an international army. Many organizations and humanitarian aid workers on the ground began to speculate about whether there were there any Rwandan refugees left in Zaire. Had they all returned to Rwanda?

According to some organizations and officials, including members of the US administration, there was no need for military intervention to set up a safe zone if all or most of the refugees had left Zaire. Others, including MSF, estimated that some 700,000 Rwandans were still trapped in Zaire, based on reliable on-the-ground information. On December 14, 1996, after pressure from the powers-that-be in Rwanda, the AFDL, and the countries supporting them, the United Nations ordered the international force, which was poised to intervene, to stand down.

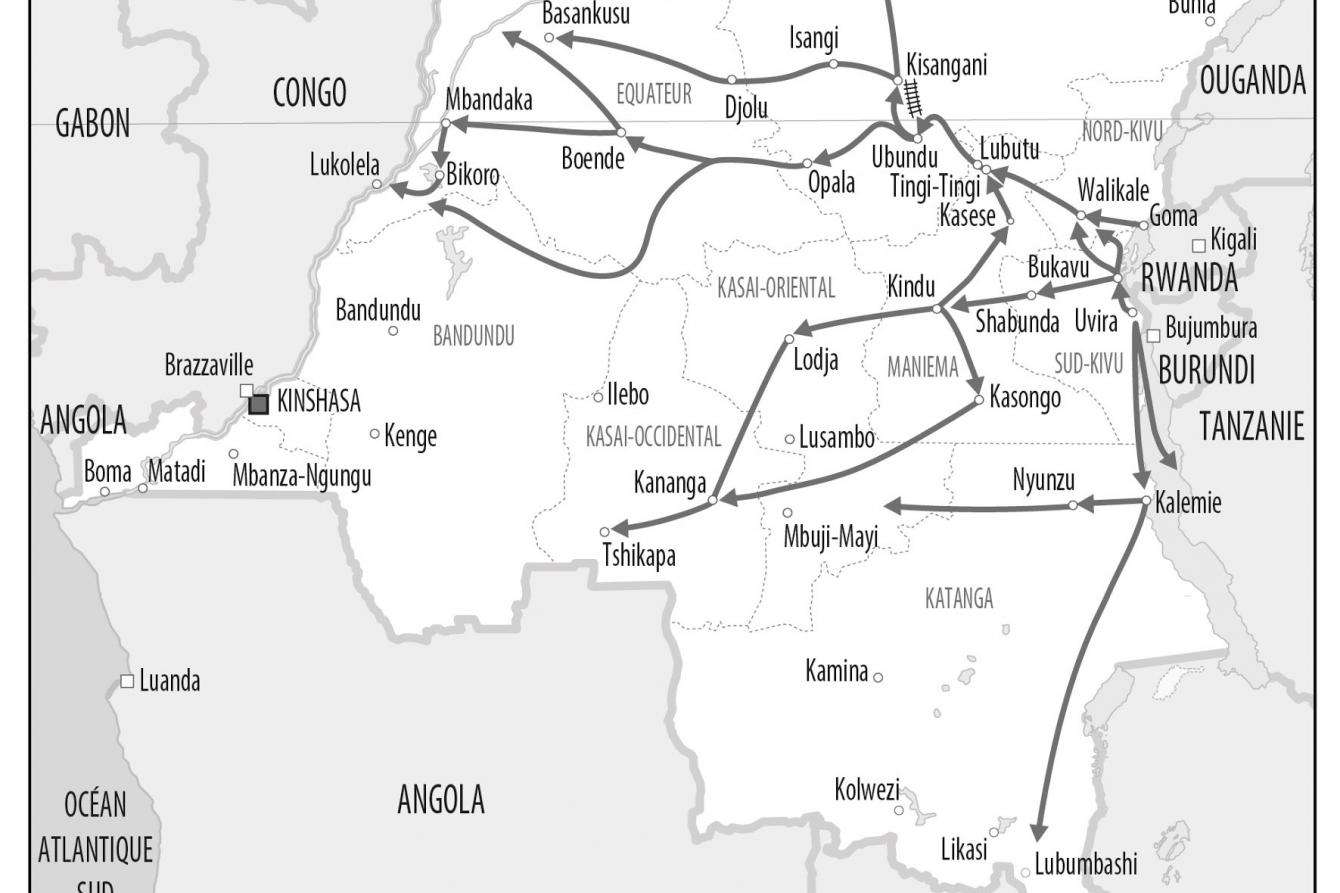

MSF teams working in the field organized an emergency response to help refugees fleeing from the fighting. They set up health posts and facilities to provide care to the men, women and children amassed in Tingi-Tingi camp, situated between Goma and Kisangani. At the end of December 1996, we estimated there were more than 70,000 refugees in the camp, and, with the advance of the AFDL and Rwandan Patriotic Army (APR), more people were still arriving.

The refugees’ needs, particularly for food, were immense, creating tensions within and between humanitarian aid organizations working in the region. Mortality rates exceeded the emergency threshold, in part due to malaria and malnutrition. In February 1997 there were more than 160,000 people in Tingi-Tingi camp. It fell to the Alliance forces in early March.

The refugees, accompanied by local people also fleeing the fighting, took flight once again, this time to the interior of Zaire. The objective of the military offensive launched by the AFDL and the RPA was to seize power in Kinshasa, secure the return of Rwandan refugees to their country, and exterminate all those who did not immediately give themselves up. Tens of thousands of refugees went into hiding in the camps and dense forests along the railway line from Ubundu to Kisangani.

The AFDL considered these people enemies, and the MSF teams assisting them belatedly became aware of a deadly plan in the making. In April 1997, AFDL soldiers were not only killing refugees on a massive scale—they were also using humanitarian aid organizations as bait to draw them out of hiding. Some camps, such as Biaro, were emptied. When humanitarian organizations were able to access them again, teams found only a few survivors among the corpses.

Some of the survivors of the massacres walked more than 1,200 miles to escape the slaughter, sometimes trekking deep into the rainforest in an attempt to reach safety in Congo-Brazzaville. It is estimated that nearly 200,000 people died during this period.

Twenty-five years later the wounds of this period are still acutely felt, both in the region and within MSF. Rwandans have faced a long and difficult road to healing, reconciliation, and justice. In DRC, North and South Kivu are still reeling from the Congo Wars ignited in part by the series of events that followed the Rwandan genocide. And MSF continues to grapple with the dilemmas posed by our medical humanitarian response to the massacres and the cascading emergencies that followed.