"With the extended protection offered by this vaccine, we can hopefully prevent the epidemics from taking place at all."

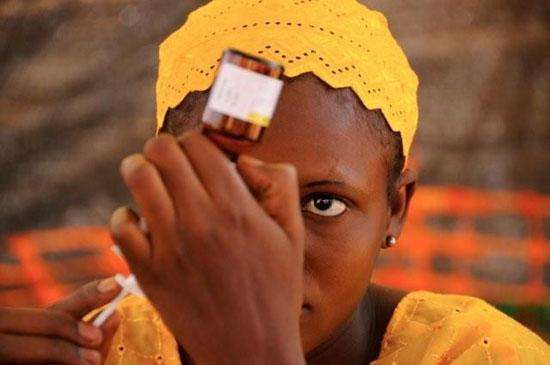

Niger 2009 © Guillaume Ratel

MSF medical staff checks a bottle containing meningitis vaccine during a vaccination campaign in Doutchy.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are involved in rolling out a mass vaccination campaign against meningitis in Mali and Niger in Africa’s notorious meningitis belt. Every year, MSF launches mass campaigns but this one is very different; the new vaccine is being employed as a preventive measure and not, as in the past, in response to an actual outbreak of the disease. This brings with it new challenges but many are hoping the new vaccine could help wipe out the devastating meningitis epidemics in the region. MSF is working closely to support the governments’ work in rolling this vaccine out which, in this initial phase, is also being launched in Burkina Faso. Dr. Cathy Hewison is a medical advisor and she starts by explaining how meningitis affects the communities in the region.

Niger 2009 © Liane Cerminara/MSF

A group of children arrives for meningitis vaccination during a mass campaign.

Every year between January and June, people in this region are on tenterhooks because they don’t know if they will be hit by an epidemic or not. Meningitis strikes children and adults across these communities and many who survive the disease will be left with long-term disabilities that can follow meningitis, such as deafness or mental disabilities. A huge amount of energy and resources has to go into combating the disease each year, from sending out teams to detect cases, to treating people and organizing the vaccination campaign, so it’s totally draining. Psychologically, financially, and physically, these epidemics are devastating for the communities involved.

Until now, MSF has responded to the outbreak of epidemics by launching vast reactive vaccination campaigns. How effective has that been as a way of managing the disease?

We’ve done our best in these situations where we are working in emergency mode, but the impact is limited due to the tools that we’ve had to deal with these epidemics. What that means is that people get ill and die because we can’t reach them on time.

First, we have to detect the epidemic, which is not easy in these countries given the time available and resources. Once the epidemic is detected, then we have to import the vaccines because there are not enough vaccines to have them on standby in every country and they are held outside the country. That then leaves us with a limited window of time to vaccinate people in order to have an impact—that period is usually the first five weeks after the outbreak, before the epidemic peaks—and it’s been very difficult to do that in the time allowed.

In addition, it’s always much, much more difficult to organize a vaccination campaign in an emergency situation, such as during an outbreak of the disease, rather than carrying out a prevention campaign when we aren’t desperately running against the clock to get people vaccinated. When people are panicking and it’s unpredictable where the next cases will appear, that puts enormous pressures on the medical teams.

Is the new vaccine radically different in that it will be used to prevent the outbreak of disease by giving people protection against the disease before meningitis has taken a hold in the community?

Niger 2009 © Guillaume Ratel

Children wait to be vaccinated against meningitis.

Yes, with the previous vaccine, because it only gave protection for a short period—up to three years—it wasn’t worth vaccinating the population before an epidemic because we can’t predict when and where an epidemic will attack. But with the new vaccine, because we know protection will last ten years, and that all these countries will be attacked by an epidemic within ten years, we know that we’re investing in a good prevention measure.

So, yes, it’s a revolution in the way meningitis will be managed because with the extended protection offered by this vaccine, we can hopefully prevent the epidemics from taking place at all.

And there are other advantages too: we can use this vaccine in younger children unlike the previous vaccine that was ineffective in children under the age of two years old. And it gives better protection to individuals than the previous vaccine which wasn’t totally effective. But most importantly, from our perspective, the vaccine will stop transmission of the bacteria that causes the meningitis within the population by eliminating the carriage of the germ. This will give what is called ‘herd immunity’. That means people who are vaccinated will protect those who are not vaccinated because they won’t pass on the bacteria.

People are saying this is the end of meningitis epidemics in this region. Is that overstating the case?

There’s no doubt it is a revolution, but we can’t say it will completely wipe out meningitis epidemics. In the first place, this vaccine has been developed specifically to protect people against a particular form of meningitis—meningitis A. It’s a specific group of bacteria that cause the major part of the large-scale epidemics across the meningitis belt. However, it doesn’t protect against all types of meningitis, so other types of what we call meningococcal meningitis will still be potentially there and it will be potentially possible to have epidemics due to other types of this kind of meningitis.

The vaccine we know is a breakthrough and has been proven in clinical trials, but won’t implementation also be key to the success of wiping out the epidemics?

The practical challenges are there. We need to ensure that 90 percent of the population that we target (one- to 29-year-olds) are reached by the vaccination campaign in order to ensure herd immunity and protect the rest of the population.That represents an enormous amount of people to vaccinate in a short space of time. It’s also much harder to mobilize people to come for vaccination if they are not immediately faced by evidence of the disease all around, so we need a very good public information campaign to get people to come forward to get vaccinated.

Once the target population is vaccinated, we need to keep that age group vaccinated which means the new children coming into that age group need to be vaccinated either through the regular annual vaccine activities or through other catch-up campaigns and that’s really a challenge we need to deal with in the future.

The meningitis belt stretches across 25 countries from west to east. Why have Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger been the first countries to step forward and implement vaccination with the new vaccine, and why is MSF so closely involved?

The first reason is that they are very frequently hit by epidemics, resulting in a high quantity of cases and deaths. In addition, these countries have been very active in meningitis, not only in reacting to meningitis outbreaks, but also in trying to advance science in these areas. MSF, which has also long been involved in innovations of treating the disease in this region, has also worked a great deal with these countries in terms of documentation and developing new treatments. So they’ve always been open to scientific research, to implementing new things that are coming onto the market, and trying to confront this problem head-on.

Most of the funding to carry out the vaccinations in the original three countries is in hand, but are there big question marks over who will fund the roll-out of this vaccine across the rest of the meningitis belt?

In fact, there’s still a gap in funding for this first phase of implementation in the original three countries. But the enormous gap in funding is indeed for all the other countries across the meningitis belt. There are 25 countries altogether which are hit by these meningitis epidemics. Of these, there are five to 10 big countries in the region with a particularly urgent need for vaccination. Here, roll-out should be done as soon as operationally possible. It’s frustrating to have this fantastic vaccine in our hands that will eventually save money as well as many lives because we will not be chasing after epidemics every year, and yet we don’t have the funds assured to roll it out. Currently, no funding is promised.

This vaccine marks a fantastic step on the road to wiping out epidemics in this region. But do we need to be even more ambitious and push for the development of vaccines to protect against other forms of meningitis?

This vaccine was developed as a result of a very special project and designed to address specifically the needs of the African meningitis belt. That need was clearly a vaccine against meningitis A, which gives rise to the regional enormous epidemics. The other criterion was that the vaccine needed to be cheap enough that the countries could afford to implement it. And the project has been extremely successful in producing a very effective vaccine for meningitis A at a very reasonable cost of US$0.40, despite the current concerns about overall funding. This cost is much less than the original vaccine we used, which was also less effective. Of course, there are other forms of meningococcal meningitis, and of course, other types of meningitis, but I think it remains to be seen if it’s necessary to have a vaccine that works against other types of bacteria and which could make the vaccine more expensive. We’ll have to see what happens as a result of the introduction of this present vaccine.

Ridding the region of epidemics is clearly the priority, but is there the intention to eradicate meningitis completely from this region?

No, that has never been a goal or even a discussion because there are so many different types of meningitis—viral, TB, bacterial—and because of the different sub groups within those different types, that makes it extremely difficult to eradicate the disease. We haven’t achieved that even in non-epidemic countries outside Africa, so that’s never been our goal.