Telemedicine helps to bridge gap between remote areas and large hospitals, links patients with specialists across the globe.

Friday at 9 a.m. Daniel Martinez, one of the three coordinators of the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) telemedicine service, receives an alert on his cell phone: the organization’s team in Shabunda, Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), has a question about a pediatric case they are treating—a five-day-old baby named Mohamed that they suspect has tetanus. Immediately, Martinez forwards the question to one of the system’s more than 280 experts around the world, both MSF and external doctors, who won’t take long to answer. This is one of more than 3,000 cases that has been treated using MSF’s telemedicine service since it started in 2010.

During these six years, the use of the telemedicine platform‐a software that allows MSF staff to manage remote medical consultations with maximum confidentiality—has not stopped growing. Currently, an average of five to ten cases are received each day. "When our colleagues in the field test the system they see that it is practical, functional, and fast, and they use it again in the future," explained Martinez, who, in addition to coordinating the service, also answers questions over the computer as MSF’s pediatric advisor in Barcelona.

For the service to be functional 24 hours a day, Martinez works with two other coordinators based in Canada and French Guiana. On average, the coordinator takes 15 minutes to forward the query coming from any MSF project to the expert and the expert takes four and a half hours to respond to the team in the field. Speed is one of the core values of the service but not the only one.

"I was so impressed with both the quality and accuracy of the answers that I couldn’t stop using it," said Kay Hodgetts, an Australian doctor who has been working for a few weeks in an emergency intervention to assist displaced people and victims of violence in Leer, South Sudan. Hodgetts remembers her first assignment with MSF in Degabhur, Ethiopia. When she arrived there in mid-2015 she had never heard of the telemedicine software but came across it on one of MSF’s computers in Ethiopia, tried it, and continues to use it regularly.

"The great advantage of telemedicine is that our patients, despite being treated in places with limited resources, can access specialized care," says Hodgetts. "Currently, widespread internet access in our projects helps bridge the gap between the level of care in the field and in large medical centers. In fact, it makes even more sense that we use telemedicine in these contexts because we have fewer diagnostic tools."

Four-year-old Mohamed was treated by Kay Hodgetts in Ethiopia with the support of telemedicine.

"It was a particularly complicated case, the child was malnourished, had fever and pancytopenia (a reduction of red cells, white cells, and platelets in the blood that is usually related to diseases that affect bone marrow), and was not responding to multiple lines of treatment," Hodgetts explains "We used the telemedicine service and sent his case history, details of how we had treated him, photos, a video, and the results of a blood test. Over many weeks and with the help of many specialists, including a pediatric hematologist, we managed to do a bone marrow biopsy to rule out a malignant tumor and thus have more confidence in our line of treatment. Fortunately, in this case, with the support of multiple specialists thanks to the telemedicine platform, we had a good result and we were able to discharge the patient in two months."

Helping to compensate for the lack of doctors

In many of the countries where MSF works, plagued by conflict or with dysfunctional health systems, there is often a lack of health workers and there are rarely any medical specialists outside the referral hospitals. Telemedicine allows doctors in the field to easily connect with experts regardless of location.

"A large proportion of our patients are children under five years old, but we work with few pediatricians," said Martinez. "Children are not just small adults and they require specific care. Knowing that many of them will be attended by staff who have no specific knowledge, it is very important to have support such as telemedicine that can give doctors guidance in the most complicated cases."

At the referral hospital in the district of Madaoua, in southern Niger, the telemedicine service has taken a further step in this direction. Every year, the country faces a peak in malaria and malnutrition from May until September, when the number of pediatric beds triples, reaching 300. For months now, doctors at the hospital have been sending their queries about cases via the telemedicine platform and then, every Thursday, they connect to Barcelona, Dakar, and Niamey to discuss the most complicated cases in depth with MSF specialists via videoconference.

"The doctors have already received the answer to their question via internet, but with these live sessions they can discuss the cases in more depth and tailor treatments as appropriate. It also serves as training for these doctors who, of course, have more limited technical resources than in more developed countries," said Cristian Casademont, medical coordinator of MSF projects in Niger. Connection problems, however, can occasionally make it difficult to do the weekly sessions.

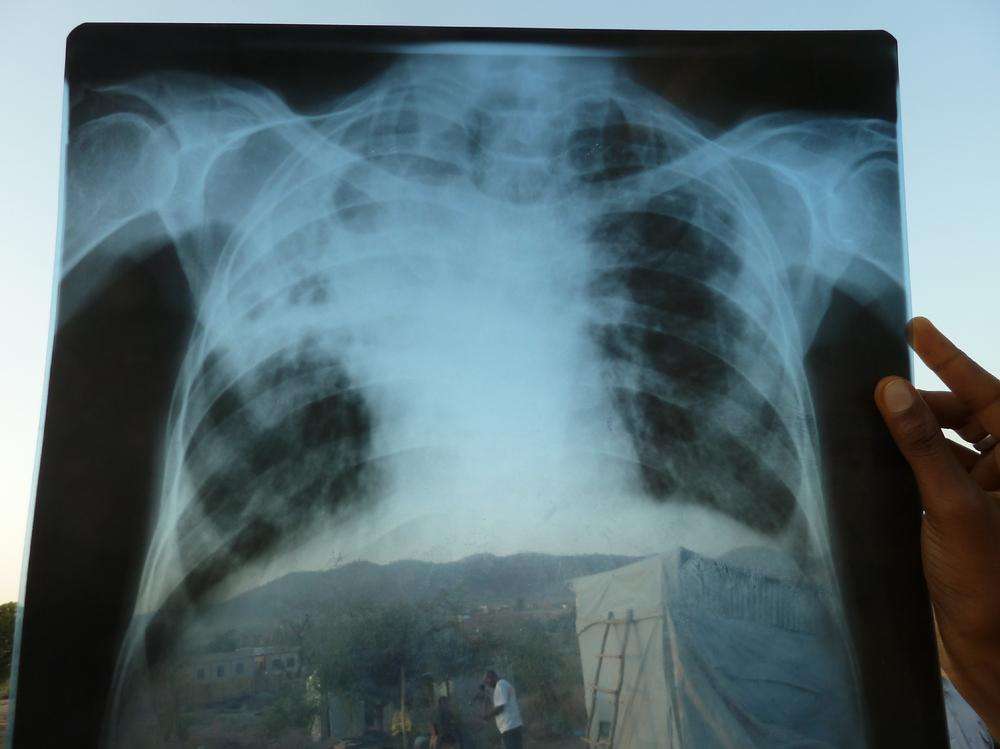

The most repeated query on the telemedicine platform is also related to the lack of specialists, in this case radiologists. Many of MSF’s HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis projects use the platform to correctly interpret chest X-rays to help confirm the clinical suspicion of tuberculosis.

Access to highly specialized expertise

"Don’t amputate. Children’s capacity for recovery and adaptation is tremendous. So just check the infection, try to close or graft the wound, and put the wrist in the correct position with a sling. Keep me informed." This is the message an MSF team in DRC received shortly after sending a photo of an eight-year-old patient with a terrible wound on one hand and wrist. Their question was desperate: "We need to know whether plastic or orthopedic surgery will be possible or if the best option is to amputate the hand."

Inquiries about surgery represent more than 10 percent of the total received by the telemedicine service and, thanks to them, doctors on the ground can receive very specialized information for their cases from, for example, orthopedic surgeons or ophthalmologists. With this information, both in surgery and other specialties, the number of diagnostic tests, treatments and unwarranted referrals can be reduced, which are often difficult to do in these contexts and also disrupt the daily lives of patients. The information helps to improve patient care, even in the most difficult cases.

"Sometimes we receive inquiries about cases that have no therapeutic option," said Martinez, who is convinced of the potential of telemedicine. "They are sad situations, but it is still important that the doctor has this information so they don’t give false hope to patients and their families, and can focus on giving them the best care possible." He smiles at receiving an email from Hodgetts from South Sudan: "I just wanted you to know: telemedicine is installed and running in Leer; and it has already been helpful."

MSF’s telemedicine system was launched in April 2010 and has grown rapidly, especially over the the last two years. In February 2016, the platform received its 3,000th case from the project in Aweil, South Sudan. In 2015, MSF launched its first project depending heavily on telemedicine—a TB program that for diagnosis relies on the support of radiologists consulted through the system.