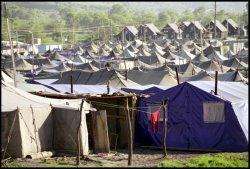

A mother and child stand within a settlement in the Karabulak region of Ingushetia. Photo © Simon C. Roberts |

In the bleak settlements for internally displaced persons (IDPs) in Ingushetia, in the temporary accommodation centers in Grozny, and in rural areas of Chechnya, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) national staff medical teams provide health care to vulnerable people. A gynecologist, pediatrician, general practitioner, nurses, and mental health counselor visit selected sites each week.

In most projects around the world, MSF international aid workers work closely with national staff colleagues, but security constraints in Ingushetia and Chechnya mean that the organization's daily work there is conducted almost entirely by national staff teams. In total, there are about 170 national staff working for MSF in the region. Here two of them describe their work, their challenges, the problems their patients face, and their thoughts about the value of MSF's assistance.

|

– Janeta |

Janeta is a gynecologist working in Ingushetia. She started with MSF in 2000 and works alongside a pediatrician and two nurses in two different kompaktniki (spontaneous settlements), which she visits twice each week. A kompaktniki can vary in size, but house as many as twenty to several thousand IDPs. MSF currently works in more than twenty kompaktniki in Ingushetia.

Janeta gave this interview in an IDP settlement that used to be a repair yard for agricultural machinery, the rusting remnants of which litter the muddy ground. Children play among pigeons and looming hangars that house multiple families in cramped conditions. And their living conditions will get colder and damper as the unforgiving Russian winter sets in. The settlement is only a few miles from the Chechen border, and not far from the site of former tent camps that housed thousands of refugees who fled the conflict. The camps were closed in 2004.

At a polyclinic in Grozny, MSF staff perform consultations. Photo © Denis Lemasson/MSF |

The tiny consulting room, fashioned out of an abandoned railway wagon and carefully roofed with corrugated iron, is decorated with information about MSF and health education posters. An iron stove gives out an intense amount of heat, so fierce in fact that Janeta and her nurse colleague are dressed simply in short-sleeved surgical greens, despite the icy temperatures outside. Basic gynecological equipment is neatly arranged in the room, with the spotless examination table tucked into a corner.

"I have worked with MSF for about five years," says Janeta. "I come from a family of doctors and specialized in emergency gynecology 10 years ago. I first worked with MSF when I helped out the MSF surgical teams that were operating on the war wounded in the Shatoi district of Chechnya, where I come from, in between 1995 and 1996: we did whatever we could. And then after that I started as an MSF gynecologist. I've worked in several different settlements in Ingushetia. At the start we worked without electricity or gas and our patients were often very aggressive and difficult. They were suspicious of us, or anyone offering assistance. But now I think that they realize that we are helping them, and it is very rare that anyone is aggressive towards us these days.

At the beginning we saw many acutely ill women–lots with severe anemia and complications in pregnancy. Many were frightened of birth too, and did not have consistent antenatal care. Now, after the years we've been working we are able to help women plan their births and their families, and gradually the health of our patients has improved.

I see about 20 to 25 patients a day, who wait in turn until we can see them. The pediatrician is even busier. The most common things I see are bleeding in pregnancy and inflammations of the lower pelvic floor. We do have the option of referring women who need specialist care to local hospitals, but to be honest, I try to minimize this and treat my women as best I can. The hospital services are expensive and the drugs are of poor quality, so many women refuse to go.

As the only doctor nearby, I am sometimes called upon to help with emergencies and it is very satisfying to be able to use my skills to help save people's lives. I find the gratitude of my patients is my biggest reward."

|

– Aiza |

Aiza*, an MSF gynecologist working in Chechnya, travels each day with a pediatrician, nurses, general practitioner, and mental health counselor for their weekly visit to five different locations in a rural area of Chechnya. The years of conflict have ravaged the local health infrastructure, and not only through physical damage. Many local health personnel fled the republic in search of a better life elsewhere. As a consequence, the rural health posts that fed larger hospitals is hopelessly understaffed. In the areas where MSF works the people often rely solely on an over-worked feldshers (nurse practitioners) who do what they can with the scant resources available. MSF has been operational in rural Chechnya since July 2005 and will soon expand its mobile team to cover another four settlements.

"Before I joined MSF just over a year ago I worked in one of the state polyclinics in Grozny," says Aiza. "But I was not satisfied with the quality of what I was doing there and the conditions in which I had to work. Now I've joined MSF and one of the best things about it is the excellent relationships and cooperation we have within our team. The more we work together the more we become like a family, and the more I enjoy my job.

Each day we have to travel for about one hour from Grozny into the countryside. The traveling is hard. Many of the places we visit are in very beautiful surroundings–set among mountains, and with pure forest all around–but most houses are either destroyed or 'wounded' by years of war. Some houses were bombed, and although families use all the spare money they have to try to rebuild their homes, you can still see the scars of the bullet holes in the gates. Some people have run out of money too, so there is a lot of half-finished construction.

In the Malgobek region of Ingushetia, a young child is examined by an MSF physician during a mobile clinic. MSF uses mobile clinics to help some of the area's 5,000 displaced people. Photo © Simon C Roberts |

In each place we work, MSF has rehabilitated a couple of rooms in the local health post or dispensary. These are small (13 feet by 10 feet) and quite basic, and we had some problems with heating and water to start with. We normally arrive to find a queue of people, and the feldsher, waiting for us. We work closely with the feldshers, who, despite not being highly trained, are made wise through their years of practical experience. They know all the ins and outs of the history of their local patients–we sometimes say that you don't need the patient's medical card, you can just ask the feldsher. They help us prioritize the sick, and ask us for advice and prescriptions. Altogether we see about 75 to 85 patients between 9 am and 3 pm each day.

Anemia is very frequent. I think of it as a social illness in fact, as is it is so common where living conditions are bad, unemployment is high, and nutrition is inadequate. We've been living in a constant state of alarm in Chechnya for so long that it ages and exhausts us and our physical health suffers. I also see lots of pregnant women–did you know that Chechnya has one of the highest birth rates in Russia? We use rapid tests for hemoglobin and glucose, and we do have access to free lab tests for our patients in one of the Grozny hospitals. But often the quality of the results isn't good, so I rely a lot on clinical signs to diagnose my patients.

Lots of what I do isn't strictly medical–time has shown me that it is really important to educate my patients too. There is, after all, no point in me treating someone if they don't also take responsibility for their own health. I remind the women that see me about basic hygiene and tell them that they should try to buy cotton underwear to avoid infections, even if the synthetic stuff is much cheaper.

I really work on persuading my pregnant women that the health of their child will depend on how they look after themselves during pregnancy–they need to rest and eat as well as possible.

We're too far away from a town to go anywhere when we break for lunch, so we collect together things to eat on our journey. Sometimes patients also bring us food to say thank you–in fact yesterday we received some manti (traditional local dumplings) and some sweet tea. We lay out what we have on our 'family' table and gather round–there is lots of laughter and jokes.

Our work only really scratches the surface. We know that lots of the ill people who come to us need extensive tests and inpatient care. But after the way that they have suffered they often have no money, and I know that if I tell them to go to hospital they won't.

In the Ingushetian city of Nazran, internally displaced people wait outside a clinic, where MSF provide approximately 700 obstetric/gynecological consultations and 50 pediatric consultations per month. Photo © Denis Lemasson/MSF |

It's not just the money but also lots of other things, like the poor drugs and the logistical difficulties of getting there, and leaving the family behind. So I try to do my best, and at least make sure that, if I can't cure someone, I can prevent them from getting worse.

Our patients express real, heartfelt gratitude for our presence. I don't think that they fully understand what MSF is, but they often say 'thanks to you and those that sent you.' For most people it means a lot to them that we have come specifically to care for them–caring has not been something there has been much of around here in recent years. One of my regular patients, a man who has had a very hard life and been in prison, even wrote a poetic tribute to our work. Personally, I get a real sense of satisfaction from what I do, and I can see the results of my work. Although I am usually really tired at the end of the day, it is a satisfied kind of weariness.

People sometimes ask me why I stayed in Chechnya and didn't leave. I think back to when I worked through the war, trapped by a blockade for months without electricity and water, and I think about the suffering I still see around me. But I reply that these difficulties have, if anything, made my love for Chechnya stronger. It is my home."

*The name of the doctor has been changed.