For the past nine months, Lisa Errol, a midwife from New Zealand, has been treating pregnant women at the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) clinic in a camp for internally displaced people in the Liberian town of Salala in Bong county. The camp developed in 2003 after tens of thousands of Liberians fled their homes as rebel and government forces clashed in northeastern Lofa county and other parts of Bong.

MSF has been providing medical assistance (including vaccinations, therapeutic feeding of malnourished children, and treatment of diseases like malaria and tuberculosis) and drinking water to the camp for the past two years. Violence is no longer a major threat but preventable diseases such as tetanus remain a serious risk to the pregnant women that Errol has treated in the clinic. Many of the women who come to the clinic are from outlying villages. Errol tells us about one of the most difficult and inspirational cases.

|

– Lisa Errol |

|

Two large frightened eyes stared up at me as I gently lifted the motionless small body from the stretcher to the to the bed. Unable to speak and barely able to breathe Alice burned with fever. Her body shook with repeated muscle spasms and her jaw was clenched tightly shut from the tetanus attacking her body. Only her eyes were open, moving from side to side as she tried desperately to identify her surroundings. Unable to eat, drink, swallow, or speak for 24 hours, she had been carried to the clinic from her village by her brothers, husband, and her grandmother. They had walked for 12 hours in the tropical heat of West Africa, trying to get to the nearest health clinic for help.

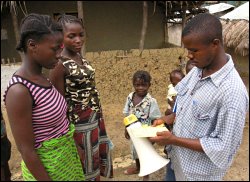

An MSF national staff member, known as a "health visitor," checks the vaccination card of a woman living in the Salala camp for internally displaced people in Liberia's Bong county in order to promote a tetanus-vaccination campaign in the camp. Photo © Jason Cone/MSF |

Six days previously she had given birth to a tiny premature baby boy weighing 1500 grams (3.3 pounds) at home in her village, attended by her mother and sisters, and perhaps, a traditional birth attendant. This is the norm in most villages in Liberia. Her drinking and washing water at home are drawn from the nearby creek, which doubles as the village latrine. Malaria and diarrhea are the most common sicknesses in her village, most often killing the young and the old. The average number of pregnancies a Liberian woman has during her fertile life is fourteen with just five or six surviving.

Isolated From Health Care

Cut off from the larger towns by roads only passable on foot, Alice had received no antenatal care during this pregnancy or a previous one. She had never had the opportunity to be immunized against those childhood diseases now so rarely seen in the West, and her wasted legs–flaccid from the polio she had suffered when she was four–bore witness to the costs of the lack of health care.

Though lovingly cared for by her family, she had rarely been carried from her house and village. In the past, a trip outside the village was undertaken only in times of severe illness or to escape to the nearby jungle, to hide from the fighters who periodically raped and pillaged the village and its inhabitants over Liberia's 14-year civil war.

Now at 18, tetanus ravaged her small body of just 30 kilograms (66 pounds). Her tiny baby wriggled vigorously beside her, asking to be fed. He was miraculously without the fever that now gripped his mother. As she fought for her life, his grandmother held him to her breast and fed him, fearful that if Alice continued to breastfeed him that he too would develop the same sickness.

Lisa Errol tells women living in the Salala camp for internally displaced people where they can receive their tetanus vaccination. Tetanus poses a real threat to many Liberian women who often neither have access to sanitary birthing facilities nor vaccination against the disease. Photo © Jason Cone/MSF |

Dangers of Pregnancy

Birth in rural Liberia is still most often on a mat on a mud floor without clean tools to cut umbilical cords, commonly resulting in infections such as tetanus. Many women remain unvaccinated against tetanus despite strenuous efforts by nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and the government's county health team who are currently trying to provide some basic vaccination services in the more accessible areas of rural Liberia.

There is no trained midwifery assistance for birthing women unless they live close to a large town with a maternity clinic. Much of the existing health infrastructure was destroyed during the war. Certified midwives are few and far between and those that are around choose instead to work in the larger towns where their wages are higher and they have access to clinics and hospitals supported by either the government or NGOs. Life in the remote village is not attractive for them, yet this is where there is the greatest need.

Continuing to Fight

In spite of these challenges, Alice continued her fight for life. Good luck, or perhaps "by the grace of god" as people are often heard to say here, meant that near the end of her long journey on a hammock to town a passing MSF vehicle, returning from an assessment in the nearby countryside to investigate local health needs, saw her and picked her up. She was brought another hour and a half by road to the MSF health clinic in Salala, two hours northeast of the capital, Monrovia.

Two weeks went by and, amazingly, Alice was still alive. The fever had left her and the muscle spasms seemed to be lessen with each passing day. The diazepam used to stop her spasms was now slowly being reduced. She was still unable to swallow and was fed high-protein milk through a nasogastric tube. But she occasionally vocalized a sound, and she even moved her arm a little, which had given me hope that she might recover soon. No one quite knew what the speed of progress would be, or what level of disability she would be left with, given that the few people I have ever seen with tetanus hadn't survived longer than a day or two. Her baby had reached 2 kilograms (4.4 pounds) and was growing stronger by the day so perhaps he would inspire her to continue her fight for survival.

Such small improvements seemed so miraculous in a place where there are no longer intensive care units, no oxygen, few blood testing facilities beyond hemoglobin readings, nothing to check electrolyte levels for calcium or potassium, no drip counters, no heart monitors, or the other such "intensive care patient machines" that hospital staff have come to rely on for quality patient care in the developed countries, and just a few essential medicines. It is a constant challenge to provide quality midwifery care here but it's thanks to MSF's support and the many people I see, like Alice and her family, that I am inspired to continue to do what I can here.

"Too Much for Her Frail Body"

But the disease was too much for her frail body to handle, and Alice died exactly three weeks after her admission to hospital. After appearing to improve at the end of the second week she declined again three days later, developing pneumonia. She never regained consciousness after this time. Her grandmother and her baby accompanied her body back to the village the following day where she was buried. I am hopeful her sister will agree to take over the feeding of her baby, as she was already breastfeeding an older child. The chances of Alice's baby surviving without his mother are slim here, but I remain hopeful for a miracle. Putting infants on formula is almost a certain death sentence because there are so few clean drinking water sources.

A young woman is vaccinated again tetanus during an MSF-run campaign in the Salala camp for internally displaced people. Some 1,400 women were vaccinated during the second round of the campaign in December 2005, providing these women with at least a year's protection against the disease. Photo © Jason Cone/MSF |

Sparking Action

With tetanus being such a looming threat for pregnant women, the MSF team in Salala decided to initiate a vaccination campaign to immunize all women in the IDP camp against tetanus prior to their return to the communities they fled from during the war. The camp will close in the next few months when the remaining displaced head home. Another MSF team is providing medical care in Kolahun, one of the major towns in Lofa county where most camp residents lived before the war.

Of the 12,000 or so remaining residents, the team calculated that 1,500 women of childbearing age remained unvaccinated or partially immunized. During a mobile clinic in November, more than 1,400 women were vaccinated who otherwise would not have received their tetanus vaccine.

And with the help of "health visitors," national staff who have been trained to raise awareness in the camp of the vaccination campaign, we completed a second round in December with nearly the same turnout, giving these women from one to three years of protection. (Four injections, the third of which must take place between six months and one year of receiving the second injection, are needed to provide immunity for ten years). The idea being that the local medical teams in their home counties will be up and running by that time, and that the MSF team in Kolahun will be continue to provide medical assistance and regular vaccinations.