The issues are serious. People lack water, electricity, and sufficient shelter, and some are facing eviction. They have children who are ill and family members they haven’t seen or heard of since they left Syria. One man says he still keeps all his belongings in a car because his tent floods.

The waiting rooms fill up soon after MSF’s clinic in Arsal, a town in Lebanon’s Bekaa Valley, opens for the day. Men and women, their fatigue visible and their children in their arms, find seats on benches until they’re called to see triage nurses who gather information and direct them to the proper part of the facility.

One of four clinics MSF runs for Syrian refugees, Palestinians, and local residents in the Bekaa Valley, MSF’s project in Arsal provides free health care to people who otherwise cannot access or afford it and would likely go without. Staff offer primary health care, pediatric care, chronic disease care, and maternal care, including obstetrics and gynecological services. The crowds are testament to the scope of the medical needs in the area, especially among the ever-expanding refugee population, many of them from Syrian towns and villages just over the border, a few miles away.

In one consultation room, Dr. Rabih Kbar, the general practitioner on call, greets the first of the roughly 50 patients he sees in a given day, a number he says has been rising steadily. In the other, Maria Luz Mendez, who supervises maternal health care at MSF’s clinics in the Bekaa, and Madonna Sleiman, a Lebanese midwife, consult with pregnant women. They see 10 to 12 per day, Mendez says, most of them from Aleppo or Homs. (MSF does not deliver babies at this facility but does provide vouchers women can use to cover birthing costs at nearby hospitals.)

The fixed site projects are only one facet of MSF’s work in the area, however. Unlike in Iraq, there are no organized camps for refugees, so Syrians fleeing to Lebanon have no obvious place to go. There are more than 1 million Syrian refugees now living in a country of only 4.4 million people. In some places, says Hanane Lahjiri, an MSF community health worker in Arsal, “it seems like you see 10 Syrians for each Lebanese person.”

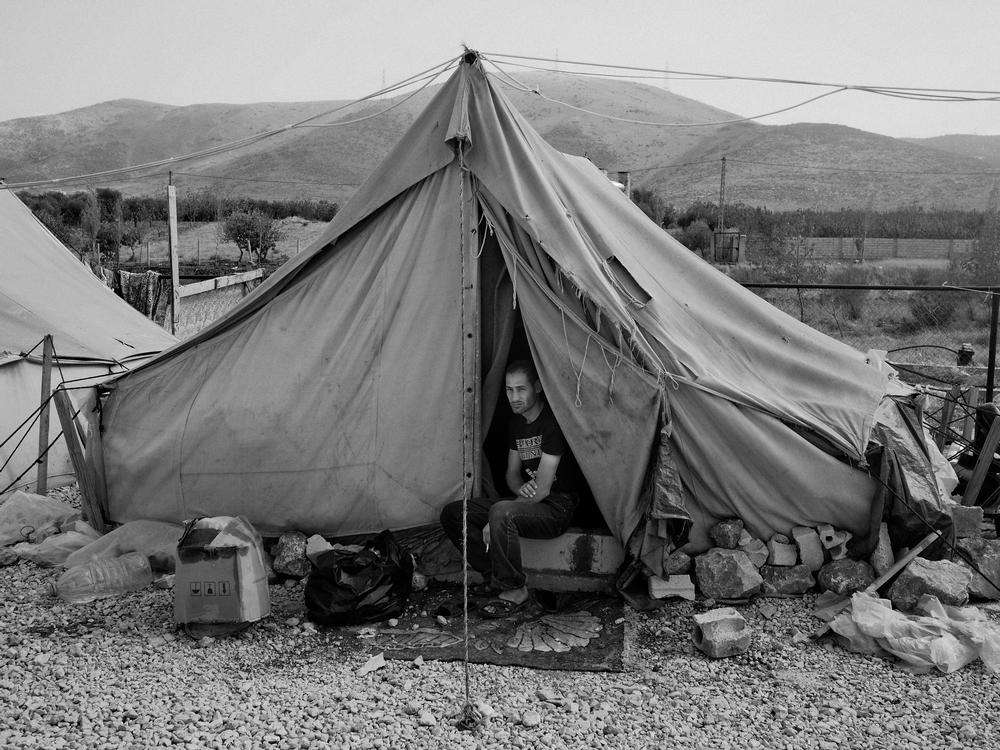

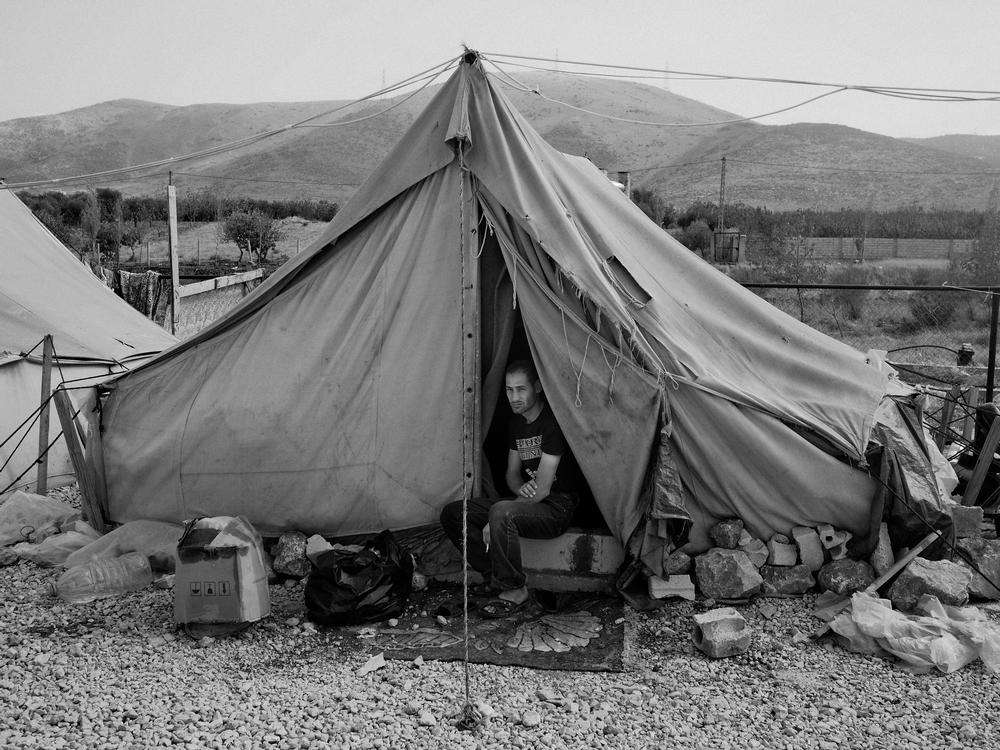

Not surprisingly, said Tania Miorin, MSF’s field coordinator in the Bekaa at the time, tensions have risen between Syrians and the host population, and between Syrians themselves. There are many local groups and individuals providing assistance, but refugees have to find their own shelter wherever they can, in settings ranging from clutches of canvas tents in rocky valleys to empty schoolhouses to hastily constructed concrete rooms to an abandoned prison. One MSF survey last fall counted 260 settlements in the Bekaa alone; a more recent survey found 450. To make matters worse, the area occasionally gets hit with shells fired from inside Syria.

The services are limited, particularly for refugees not registered with the UN. Fuel, in particular, is increasingly hard to come by, and many families were unprepared for this past winter. As a result, MSF staff started seeing more patients with acute respiratory problems, gastrointestinal problems, and skin diseases. More people have also been presenting at clinics seeking care for chronic diseases that have gone untreated since Syria’s health system collapsed.

Too often, though, people do not know where they can access medical attention. It’s not enough to wait for people to come to the clinics, however. MSF staff have to seek them out. So while the team at the Arsal clinic was hard at work, Lahjiri set off with Sarah Hamood, an MSF social worker and a Syrian volunteer, for a day of driving from one refugee settlement to the next. Some they’d been to before. Some they had heard about only recently and would need to locate. “Before, it used to be easier to identify the needy cases,” says Hamood. “Today, they are more numerous and more scattered.”

The first stop on this day is the Abu Ismael settlement, a collection of 30 to 40 concrete rooms a Lebanese landowner rents out to refugees. Lahjiri wants to check in on a woman whose baby died shortly after being born. Later, she and Hamood go to two other settlements, meeting with community leaders, patients, heads of households, and anyone else from whom they can learn about the general health of the people at the site and with whom they can share information about MSF’s services.

The issues are serious. People lack water, electricity, and sufficient shelter, and some are facing eviction. They have children who are ill and family members they haven’t seen or heard of since they left Syria. One man says he still keeps all his belongings in a car because his tent floods when it rains. One woman lost her husband and home to the war and had to send her teenage daughter to live with an uncle because the latrine in her settlement is too far from her tent, which makes it unsafe for girls at night. “We used to have a happy life,” she says.

The roads in the Bekaa wind through valleys and roll up and over hills, but wherever MSF staff travel, they find people seeking assistance. And as the war grinds on, the numbers, and the needs, continue to grow.

In 2013 alone, MSF staff carried out more than 50,000 medical consultations in the Bekaa Valley, a quarter of them for children under the age of five.