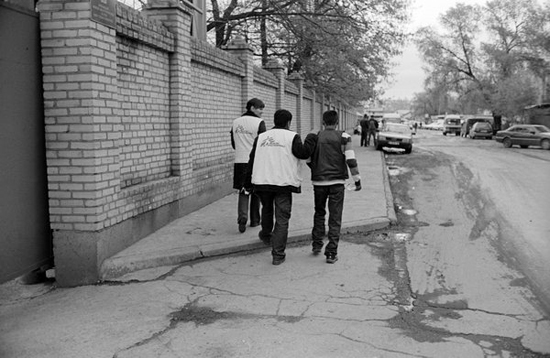

Kyrgyzstan 2009 © Alexander Glyadyelov

In Kyrgyzstan, a team of MSF community workers and a network of volunteers assist former prisoners with tuberculosis to complete their treatment regimes for the deadly disease.

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) is on the rise worldwide and kills around 120,000 each year. The treatment of MDR-TB is very time-consuming and has prohibitively negative side effects. Many patients have difficulties remaining in treatment for up to two years and must at the same time endure the social stigma that comes with being infected by the deadly disease.

He is a free man now, but Ruslan has gone back to Colony 31, a special penal colony in Kyrgyzstan for prisoners suffering from TB , to celebrate with his doctors the completion of his long, arduous, and painful treatment for MDR-TB.

"It was like a nightmare, you can’t imagine how difficult it was to take those drugs."

—Ruslan, Kyrgyz TB patient

"It was like a nightmare, you can’t imagine how difficult it was to take those drugs," Ruslan says. "You want to sleep but you can’t, you feel dizzy, you feel nauseous, you vomit, but you don’t feel any better. I took the drugs even though I felt awful but my former cellmate couldn’t keep going. For him the side effects were too much."

Every year, 120,000 people die from MDR-TB and nearly half a million new cases are identified. The number of patients suffering from strains of the disease that are resistant to one or more drugs is growing—the World Health Organization estimates two million cases worldwide. Most patients develop MDR-TB because they are not treated properly, but people are increasingly contracting MDR-TB the first time they are infected.

Treatment for MDR-TB is costly and complex. The drug regimen duration is up to two years with severe side effects and a cure cannot be guaranteed. Side effects range from unpleasant to unbearable and even dangerous. Several MDR-TB medications have terrible gastric effects, trigger nausea, and cause the kidneys and liver to malfunction. To counter such side effects, the only solution is to add more tablets to the already high daily pill count.

Kyrgyzstan 2009 © MSF

Ruslan, a former prisoner from Kyrgyzstan, who has been cured of his multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and went back to his former prison to celebrate with doctors and other medical staff.

In Kyrgyzstan, a landlocked and mountainous country in Central Asia, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been operating a TB treatment project since 2006 in collaboration with the International Committee of the Red Cross. The project is based at two sites—Colony No. 31, a penal institution, and SIZO No. 1, a pre-trial detention center—both located near Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek.

One in three prisoners with TB is released before the completion of treatment and faces enormous obstacles once outside the penitentiary system. Since they struggle with little help for the basic necessities of life and some deal with alcohol or drug addictions, many ex-prisoners do not see their treatment as a high priority. Some may not even have the money to reach the nearest TB facility. If they do come, they may not be accepted because they don’t have the proper documents or because medical staff are unwilling to treat former prisoners.

"I was released in May 2008, right in the middle of my treatment," Ruslan says. "While I was in the colony the community workers explained to me how I could continue treatment in the civilian sector. But when I got to the hospital, the doctors looked at me with suspicion. ‘Ex-prisoner…..criminal’ they said. But after a while, because of my good behavior, their attitude towards me changed."

"Our patients face the double stigma of not only having TB but also having been in prison. In addition, they may be homeless, unemployed, be dependent on alcohol or drugs and without identity papers."

—Umutai Dauletova, MSF social support coordinator

Umutai Dauletova, MSF’s social support coordinator affirms that it can be difficult for ex-prisoners with TB to be admitted to public hospitals. "Our patients face the double stigma of not only having TB but also having been in prison," Dauletova says. "In addition, they may be homeless, unemployed, be dependent on alcohol or drugs and without identity papers."

Today, around 70 former patients are being supported by a team of MSF social workers and a network of volunteers to complete their TB treatment. Support includes counseling, information and education, food parcels and money for transport.

"We are trying to implement a case-management system now," says Dauletova. "It’s a community approach where volunteers help patients adhere to their treatment."

Ruslan works as a volunteer case manager and offers support to some TB patients who are on treatment in the hospital near where he lives. "With the help of the MSF social team I try to cope with my responsibilities as a case manger. My message to the people I support is 'Patience, patience, patience and don’t lose hope!' "

From 2006 to 2009 MSF has supported 2,270 TB cases, including 200 MDR-TB cases in Colony No. 31 and Sizo No. 1. MSF’s TB project includes the provision of training, drugs, the equipping of laboratories and the rehabilitation of the prison hospitals and living quarters for TB patients. MSF has overseen the introduction of internationally adapted treatment protocols in the penitentiary system and has assisted the Justice Department and the Ministry of Health to improve the medical care of TB patients in prison. In 2007 an MSF office of social support was opened in Osh, the largest city in the south of Kyrgyzstan, to help former inmates to continue their treatment.