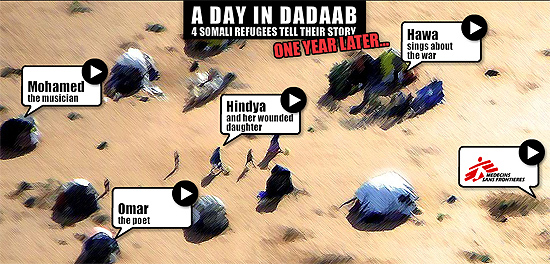

MSF staff report a grave shortage of shelter despite up to 1,500 new arrivals every week.

Somalis fleeing the fighting in their own country continue to arrive as refugees in Dadaab, just across the Kenyan border. The three vast refugee camps there are already too overcrowded to house them, and new arrivals have no choice but to construct makeshift shelters in the desert beyond the camps. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is helping the new arrivals by providing them with shelter materials and much-needed medical care while they wait for somewhere more permanent to live.

Jahara Ahmed Abdi, 35, recently arrived in Kenya with her husband and three surviving children. They desperately wanted some kind of sanctuary from the violence that is tearing their country apart. The family had lived in the Somali capital, Mogadishu, but when Jahara’s eight-year-old son was killed by shelling, they decided that it was simply too dangerous to stay. They paid $150, about half what many Somali families earn in a year, to be taken to the border. Once across, they found themselves in the arid desert near the Dagahaley refugee camp.

Dagahaley is one of three refugee camps in Dadaab, in northeast Kenya. The camps were set up in 1992, a year after the country had plunged into civil war, to house Somali refugees. Originally built to accommodate 90,000 people, Dagahaley today has close to 300,000 inhabitants.

MSF has been working in the camp since 2009, running a 110-bed hospital and four health posts. “Each week, we have 1,400 or 1,500 new arrivals from Somalia,” says Mohammad Daoud, MSF’s field coordinator in Dagahaley. “This is making the camp very overcrowded, and it means there is less space and many more difficulties for those who are already living here.”

With no end to the fighting in Somalia in sight, Daoud predicts that many more refugees will arrive. After travelling long distances, frequently on foot, refugees are often exhausted and suffering from a host of medical problems. The health needs in Dagahaley are huge, and MSF’s hospital and health posts are already overstretched. Currently 600 patients are admitted to the hospital every month, and staff carry out an average of 10,000 outpatient consultations.

New arrivals are forced to find somewhere to live outside the boundaries of the congested Dagahaley camp. When Jahara Ahmed Abdi and her family arrived in late October 2010, other refugees helped them build a hut to live in. MSF contributed plastic sheeting so they will have some protection when the next rains come. There are no latrines, however, and there is nothing but open scrubland behind their hut, so they constantly worry about hyenas attacking their children. They have not yet received any food rations from the authorities and are instead relying on neighbors to share what food they have.

Kenya 2010 @Nenna Arnold/MSF

A new arrival from Somalia, exhausted from the journey, is looked after by one of MSF’s mobile team outside Dagahaley.

At present, there are 5,000 people living in the makeshift settlements outside Dagahaley. About 700 new families arrived between August and November of this year, all of whom are now living in dire conditions in makeshift huts and shelters. The area is prone to flooding, and when the first rains of the season started in early November, the temporary settlement was inundated. Many families lost their food rations and the few belongings they had.

The rainy season is likely to last until January. Living in such difficult conditions, without proper shelter, people’s health is expected to worsen. Stagnant water brings the risk of waterborne infections and diarrhea, while children are at particular risk of developing respiratory tract infections.

The MSF team is on-hand around the clock to help with the medical needs of new arrivals like Jahara Ahmed Abdi. “We usually do a medical screening, we give them vaccinations, and we bring them to the hospital if necessary,” says Daoud.

Recently, he recounts, “An old man approached us and told us that he had found a very sick man. We came upon a lone tree in the middle of nowhere. In the sparse shade was a tired-looking donkey, a donkey cart, two goats, five dust-covered children playing in the dirt, and a young man lying motionless on a blanket. The family had arrived that day, having traveled from Somalia. The young man’s wife had gone to look for help or for food. We weren’t sure. The young man tried to sit up, but couldn’t manage it without help. He hadn’t eaten for days. It was obvious he had a high fever and needed to go to the hospital. Fortunately, the old man offered to take care of the three small children until their mother came back.”

The following day, Daoud visited the young man in hospital. “He was still very ill, but the fever was gone. We went back to look for his family and found them with the old man, who had been just a stranger to them the day before. He had found them a small hut to sleep in and had shared his food ration with them.”

Of late, the situation of the families living outside Dagahaley camp has improved slightly. Each family now has a shelter, and some—though not all—parts of the settlement have been provided with clean water. There are still no latrines, however, and people are still waiting to be relocated to a new camp, an extension to one of the existing camps. But the opening of the extension has already been postponed several times and is not likely to take place until January at the earliest. In November, MSF issued a press release calling on the Kenyan authorities and aid organizations to move the refugees to suitable accommodation immediately. Until that happens, the families continue to wait. And more refugees continue to arrive.