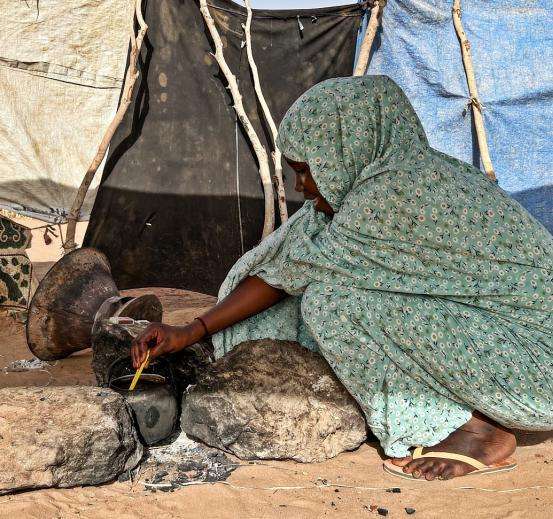

Since the war erupted in Sudan in April 2023, more than 600,00 people have fled the violence to eastern Chad. Most are women and children because many men have been killed, detained, or disappeared in Sudan. Many Sudanese women are now the sole providers for their families, bearing the full responsibility of caring for their children while struggling to access basic needs like food, water, and medical care.

Refugees are living in extremely poor conditions in isolated desert areas like Metche and Aboutengye, where they are exposed to health and protection risks. In Metche and Aboutengye, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams are providing maternal, pediatric, and primary health care, as well as treating children for malnutrition and distributing most of the water in the camps. Despite these efforts, the overall humanitarian response in eastern Chad has been inadequate to meet the needs.

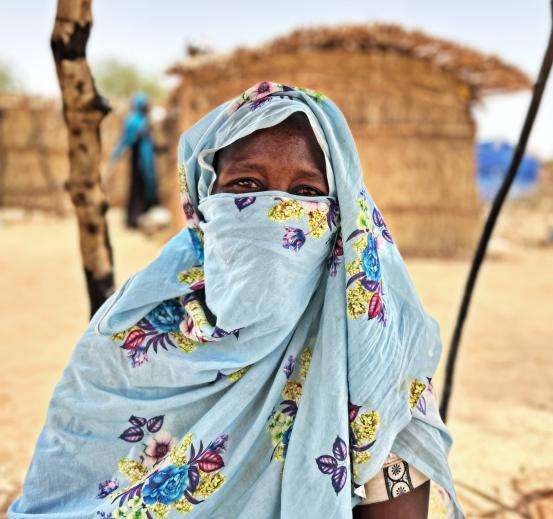

Refugee women in Chad selling goods to make money. Chad 2024 © Juan Carlos Tomasi/MSF

Testimonials from Sudanese women fleeing violence

Many of the refugees have fled ethnically targeted violence in El Geneina, the capital of Sudan’s West Darfur state, which borders Chad, particularly during a massive influx of refugees in June 2023. Among them are courageous women with unwavering determination to protect their families. These are some of their stories.

Taiba, Aboutengue camp

"To save our lives, I denied the truth"

Taiba arrived in Aboutengue camp in July 2023 after fleeing Sudan with her husband Bashir and their two eldest children, Aya, 6, and Ayoub, 2. Their youngest, Ayat, was born four months ago at the MSF emergency hospital in Aboutengue.

"That day [June 16], I was at home with our two kids and my husband was out nearby. Numerous armed men attacked and looted the area. They took our car and entered our house. They threatened me with a gun to my neck and asked, 'What tribe are you?' We are from the Masalit tribe, but to save our lives, I denied the truth and replied, 'I’m from Borgo, I’m not Masalit.' They forced me to speak in the Borgo language to make sure I was telling the truth. Fortunately, I managed to speak a few words and they let me go. Some of my neighbors are from the Borgo tribe so over the years I’ve learned some words from them, just in case. I think that if I hadn’t lied about being Masalit, we would have died that day ...

Nafissa, Aboutengue camp

"That man saved my life with his."

Nafissa fled El Geneina in June 2023. Her husband was killed in 2022 during a previous period of violence. She currently lives with two of her children in Aboutengue refugee camp.

"The war escalated last year, but there was violence in our region before that. In recent years my house was set on fire four times. My husband was killed in 2022, and one of my sons was killed in May 2023. My son was only 10. He was shot in the street and died from his wounds in the hospital three days later. So, when I heard about new attacks coming to our neighborhood [in June 2023], I left my home with my last two children and I’ve never gone back.

I dressed my 11-year-old boy in his sister’s clothes and we set off together on foot. I took only two blankets, a few clothes and a jerrycan for water. But the armed men took everything from me on the way, saying, 'No one takes anything with them to Chad.'

On the streets, we saw a lot of dead bodies. We were following the flow of people; it was very crowded. At one point, we were walking towards Ardamatta to find refuge, [where the army was]. We heard gunshots, armed men started shooting at the crowd, and people were running everywhere. That was when I lost my daughter. She was so frightened that she ran with the others ...

Gamera and Jeta, Aboutengue camp

"I dressed them in girls' clothes so they wouldn’t be killed."

Mother and daughter Gamera, 60, and Jeta, 35, fled El Geneina together with Jeta’s five children. Upon their arrival at Aboutengue camp, Jeta’s youngest daughter was suffering from severe acute malnutrition and was successfully treated in MSF's therapeutic feeding program.

Gamera: "Early in the morning, armed men attacked our home. They called my three sons into one room and made us [the women] leave the house. I begged them not to kill my boys, told them that they were innocent, as they somehow accused them of being spies. But then I heard the gunshots. When I came back to the house, I saw the bodies lying on the floor. One of my sons was shot in his chest, the other in his head, and the third in the neck. Then the armed men threatened me with a knife to my throat and stole our money and phones. They even checked my body to see if I was hiding anything. As they left, they set the house on fire.

We fled on foot from El Geneina to the border with Chad. We saw a lot of dead bodies on the way. It was very crowded, and we lost each other in the flow of people. It was only after crossing the border that we found each other again ...

Malak, Metche camp

"I hope to return to Sudan in peace and security."

"It was 4 o'clock on a Friday, and my husband told me that there would be an attack. “Take the children and go to your sister’s house,” [he said], “and I will go to the gardens [El Geinena].”

I opposed the idea, but he went there, where he was killed. He was an innocent person. Me and my brothers and his brothers kept searching for him for four days. Finally, there was a strange smell where we were searching. They searched until they found him and told us that his body was there. His name [was] Jaafar and he was 42 years old. At the time, there were too many shooters, so his brothers and some neighbors had to sneak in to retrieve his body so we could bury him.

When I arrived in Adré, I couldn't find my mother and three of my children. I searched for them for four days. When I finally found my mother, she was in a terrible state. I was reunited with my children. We stayed two months in Adré until we settled here in Metche, where I gave birth to my child ...

Ghalia, Aboutengue camp

"We are not getting killed, but we have nothing to eat."

Ghalia fled Sudan with her husband, their five children, and two of her brothers. They arrived in Aboutengue refugee camp in July 2023. Ghalia gave birth to her youngest daughter, Makarima, at the MSF emergency hospital a few months later.

"The increase of violence in my neighborhood was horrible. I cannot count how many people were killed in the streets, with gunshots and bombs. The day of the attack on my house, I started running, my youngest one strapped to my back. There were so many people outside that I lost my other children and my husband. I remember heading to Ardamatta in the night, but armed men were waiting for us. In the morning, they shouted, 'No one moves' and told us to leave our money and our guns. Then they started shooting at the crowd. People were running everywhere. It was chaos; people were coming [in] waves. The armed men told us to turn around and take the road to the west, the one that goes to Chad.

In the next village, I managed to find my children—they had managed to stay together and support each other. They were thirsty, hungry, tired, and afraid. They were crying. But I was so relieved. I had thought I would never see them again; I had thought they were killed. I felt so happy and relieved to find them ...

Ruqaya, Metche camp

“I am now the mother and the father.”

"I lost my husband in El Geneina on June 15 [2023], when the fighting escalated that day. He is missing and so is his family.

I have two children and the living conditions are very difficult, and I have no one to support us. All the responsibilities fall on me. I am now the mother and the father. I'm responsible for food, water, shelter, and providing treatment if the children get sick. I must manage and deal with everything on my own.

People here are hungry and thirsty. There is no food. There is no security in Sudan, and we cannot return. We are living day by day ...

Gisma, Aboutengue camp

"I had no choice but to run."

Gisma turned 18 three months ago. She lives in Aboutengue refugee camp with her mother and her five sisters and is often the family's main breadwinner.

"We fled El Geneina in June last year. It was very difficult. My dad was killed. During the attacks, we left the house together with my family, but we lost each other on the way. I was with three of my sisters, carrying the youngest one on my back. In the street, we crossed paths with armed men, and they took two of my sisters. They hurt them, but … we can’t talk about that. I had no choice but to run.

We crossed the border and arrived barefoot in Adré as we could not take anything with us. We were exhausted, thirsty, and crying. Some people helped us and gave us water. A nice lady shared her food with us. I felt relieved to reach the border, especially when I met my sisters and mother again ...

Sudan crisis FAQ

For more than a year, large parts of Sudan have been experiencing ongoing violence, including intense urban warfare, gunfire, shelling, and airstrikes.

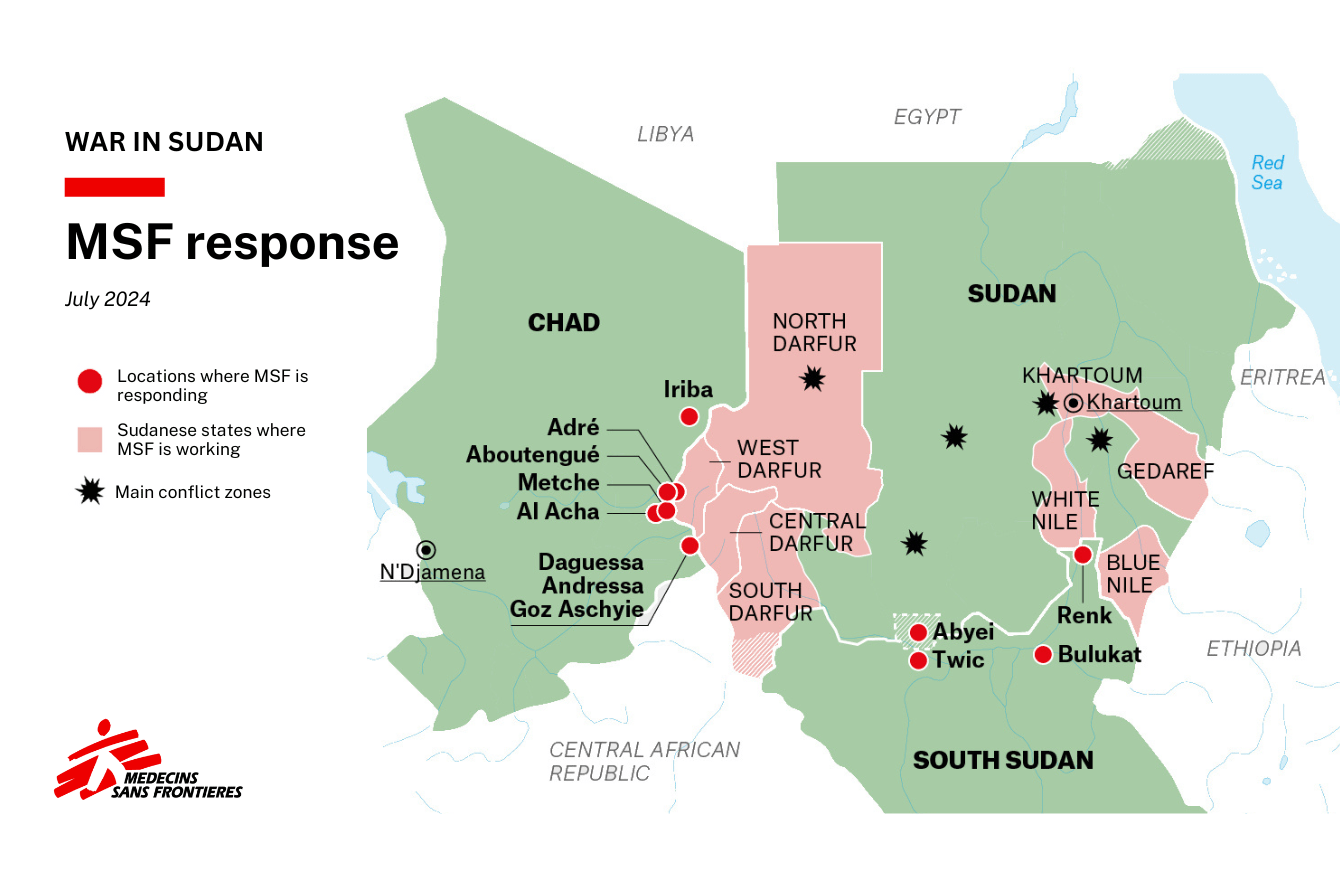

MSF currently works in eight states across Sudan, supporting 14 hospitals and seven primary health care facilities and clinics, and running mobile clinics in two camps.

Since the war broke out last year, an estimated 682,000 refugees and returnees have crossed the border to Chad.

Chad

Since the war broke out last year, an estimated 682,000 refugees and returnees have crossed the border to Chad. Refugees and returnees from Sudan are now living in multiple camps in Chad and face difficulties securing even the most basic needs. MSF teams are responding in five locations in eastern Chad: Adré, Ourang, Metche, Alacha, Daguessa, Andressa, and Goz-Aschiye, Kimiti province.

In June 2023, more than 850 war-wounded Sudanese, mainly with bullet wounds, were received in the MSF-supported hospital in Adré in the space of just three days. Hundreds of thousands of people previously trapped in West Darfur joined them en masse from June onwards. We heard horrific stories of violence from survivors, including sexual violence. We conducted a retrospective mortality study in refugee camps asking families about relatives who have died, finding that refugees from West Darfur’s capital El Geneina were particularly affected, with a mortality rate 20 times higher compared to before the conflict began. In the camps of eastern Chad there is currently an outbreak hepatitis E, which has been exacerbated by poor sanitation and a desperate shortage of clean water in the camps. In Adré camp, there is just one latrine for 677 people, while in Metché camp there is one latrine for 225 people. Without swift action to improve sanitation infrastructure and enhance people’s access to clean water, there is risk of a surge in preventable diseases and unnecessary loss of life. MSF is currently providing more than 70 percent of the drinking water available in Adré, Aboutengue, Metché, and Al-Acha camps. Despite this, people are receiving just 11 liters of clean water per day—well below the 20 liters per person per day recommended for emergency settings. Despite our efforts, the humanitarian response in eastern Chad has been hampered by insufficient funding for humanitarian organizations on the ground, leaving critical gaps in the provision of food, water, and sanitation.South Sudan

Since the beginning of the war in Sudan, over 740,000 people have crossed into South Sudan to seek refuge. The majority are South Sudanese returnees—people who had previously fled to Sudan during the civil war in South Sudan, which ended in 2018.

The influx of displaced people has further stretched an already overwhelmed system. In the transit centers, the situation is getting worse with increasing food insecurity and health issues including severe malaria cases, eye infections, acute bloody diarrhea, and risk of cholera. There is a lack of funding for water, sanitation and hygiene programs across South Sudan, which is particularly concerning as acute watery diarrhea is a top comorbidity among acutely malnourished children under 5 years old admitted to MSF facilities and as cholera outbreaks have been reported in Sudan.

MSF is responding to the refugee crisis in Renk and Bulukat in Upper Nile state. MSF’s Abyei project is also impacted, with a largely under-estimated 17,404 returnees who have arrived through the Amiet point of entry.