In Zémio, in the far southeast of Central African Republic (CAR), Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has partnered with the local Ministry of Health (MoH) to support a 30-bed health center with inpatient, outpatient, maternity, laboratory, and HIV/TB services, and runs an outreach program. The project started in 2010 in response to a large influx of Congolese refugees, as well as internally displaced people who were forced out of their homes due to repeated violent attacks by the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA). The Zémio Health Center remains one of the only secondary care facilities in this rural region and receives patients from as far as 155 miles away. Keri Geiger, an MSF nurse from the USA, shares the stories of patients from the HIV program in Zémio.

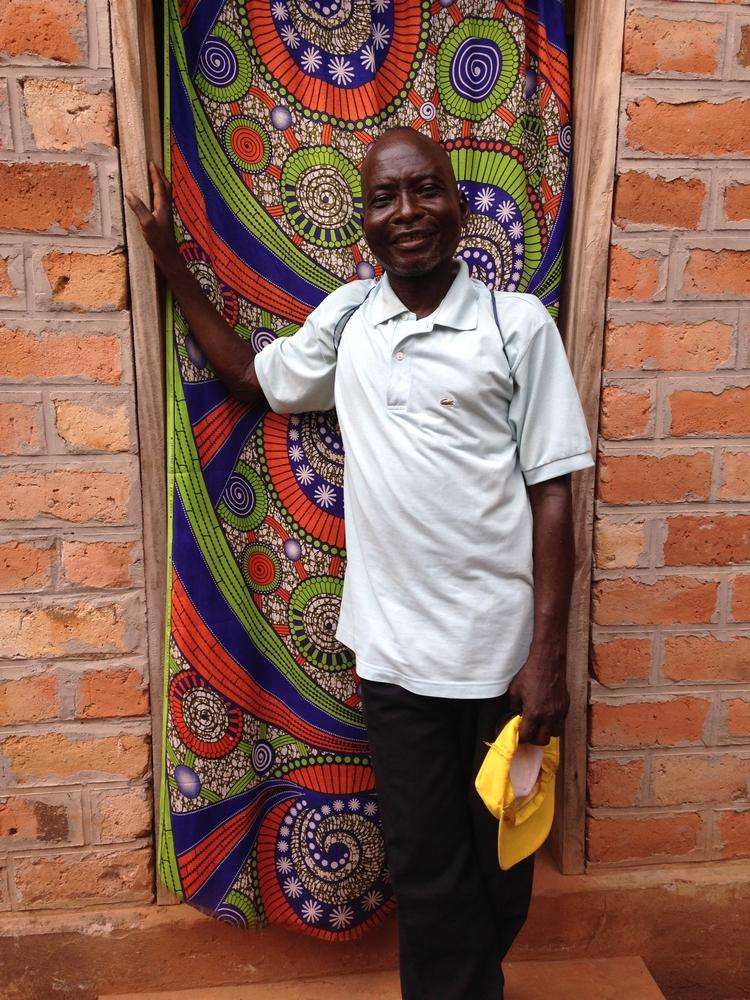

Patient Story: Jean-Pièrre, 53 Years Old

Jean-Pièrre comes from Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). He is the type of person who loves to talk about his children and his grandchildren. But he hasn’t seen them since 2012.

After the war in DRC, Jean-Pièrre was in bad health. He was tired and weak, unable to work. "I was in a critical state," he tells me. He knew he needed to be tested for HIV, but the closest testing center in DRC was over 250 miles away. That’s when he decided to come to Zémio, which, at 82 miles away, was much closer but across the border in the Central African Republic (CAR). The journey took five days on a bicycle. Jean-Pièrre, of course, was too weak to help pedal. But his brother carried him on the bike, knowing that in Zémio, MSF had a program that could help.

Jean-Pièrre tested positive for HIV. At first, his life in Zémio was difficult. It takes time to recover strength after being so sick for so long. And, of course, Jean-Pièrre was an outsider in CAR. Jean-Pièrre became used to hearing, "He has AIDS, he has AIDS, don’t touch him." He wonders what would have happened to him if some members of his church had not brought him food. To make matters worse, Jean-Pièrre was not improving clinically. He continued to be plagued by weakness and stomach pains, two of the most common complaints of the HIV cohort in Zémio. His CD4 count (the strongest predictor of HIV progression) remained low (the higher a CD4 count, the better a person is able to fight HIV and other infections). But he stayed in Zémio, knowing that the treatment MSF offered could save his life.

After two years, the MSF team realized that Jean-Pièrre’s treatment regimen was failing him. After many more tests and consultations with HIV experts in Europe, Jean-Pièrre was changed to second line antiretroviral drugs in 2015. Little by little, he began to get better and recover his strength and his spirit. He continues to suffer from muscle pain, joint pain, fatigue, jaundice, and stomach cramps. If he doesn’t eat a good meal before taking his antiretroviral pills at night, he feels very sick or has nightmares. Still, he keeps taking the treatment, knowing that these drugs are keeping him alive, and he does finally feel like he’s slowly regaining his health.

Jean-Pièrre has many plans for his future. He says he has seen me running through the town in the morning and he would like to be strong enough to do something like that one day. He also wants to start a business. He works as a farmer, but he only grows enough to keep himself fed. He is interested in making soaps, but it costs a lot of money to set up a market stall. If he were able to have a small business, he could hire laborers to take care of his fields, then he might be able to travel home regularly to see his family.

When I ask if he has had any contact with them since he left DRC, he explains that it is difficult to communicate across the border because there is no mail service, phone calls are too expensive, and, because of his ongoing health problems, travel is still impossible. "One day, maybe," he tells me. "This is a treatment for life. If you follow the program, you know that, over time, your health will get better. Life is always a struggle, but there are moments of happiness."

As for the town of Zémio, Jean-Pièrre feels there is still some work to be done to end the stigma of living with HIV. He is happy that MSF will continue to work with the community to increase their understanding of the disease. "Sensitize the population. Create better respect for people with AIDS. More people die of malaria or tuberculosis," he says. But he does feel like things are getting better for him and his community of Congolese refugees. "Thank god for MSF. You bring hope to my community."

MSF first worked in CAR in 1997, at a time when mortality rates in some regions were up to five times the emergency threshold. In the years since, CAR has continued to face a situation of chronic and prolonged health emergency. Since 2013, the political crisis and renewed violence have shaken the country, exacerbating the health situation, and leaving 72 percent of the country’s health facilities damaged or destroyed. In response to the recent crisis, MSF has doubled the size of its medical response, and now runs 17 projects across the country. Currently, one in five Central Africans are displaced from their homes, either within CAR or living as refugees in neighboring countries.

Read More: "We Need People to Understand What it’s Like to Live with HIV"

Treating HIV in Central African Republic