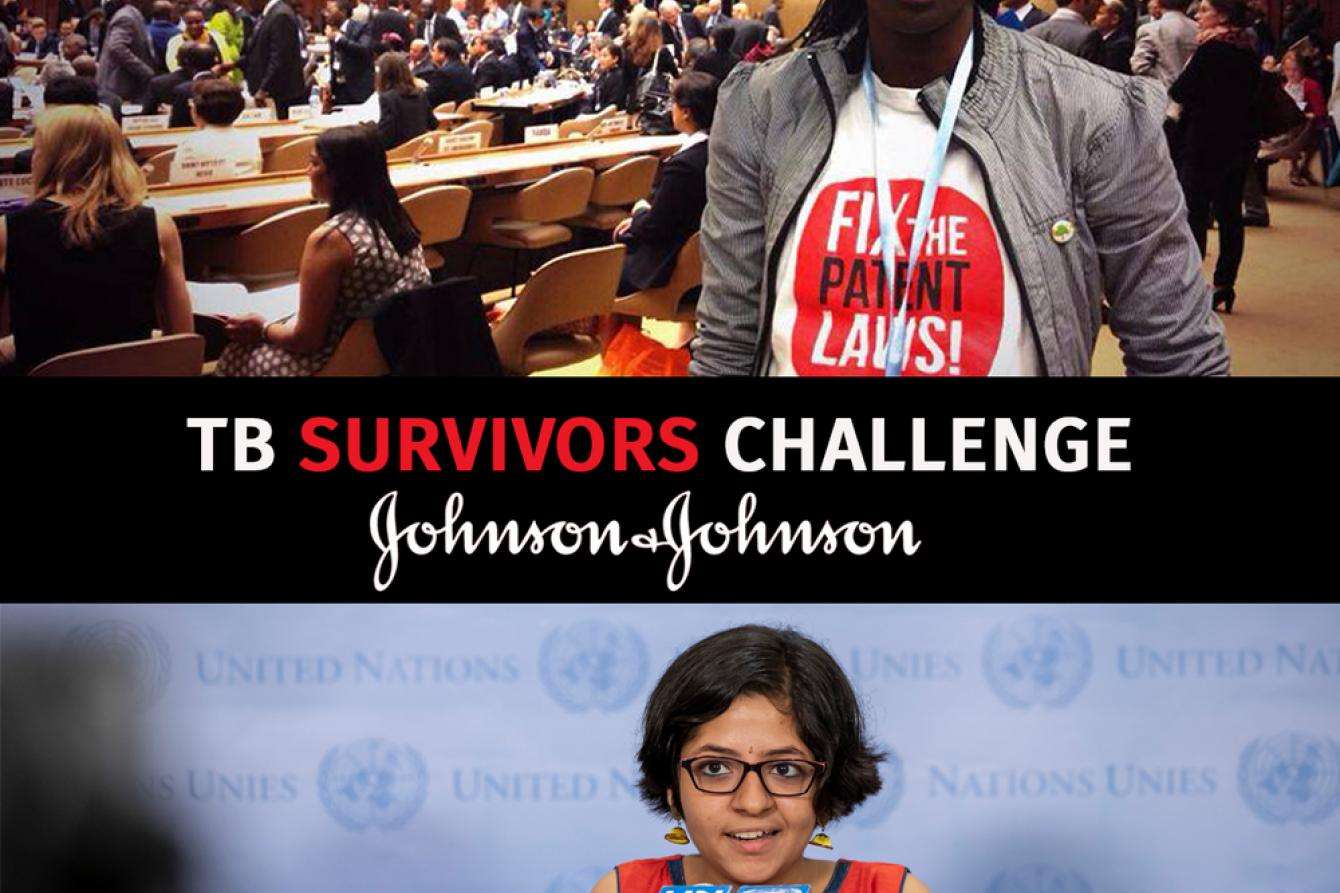

Soon after celebrating her twenty-fourth birthday, Nandita Venkatesan woke up from a nap to a sharply altered reality. She had recently completed treatment for tuberculosis (TB) and was living at home in Mumbai, India. Suddenly, she could not hear anything. “I woke up to complete silence,” she later told a TEDx audience in Jaipur. “I could see my brother talking to me. I could see the TV playing in front of me… But there was no sound in my world at all.”

Venkatesan lost her hearing due to a brutal side effect of kanamycin injections, one of the medications that was supposed to help cure her of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). “I was devastated,” she said. “How many more people will have to die or go deaf, waiting to access safer and more effective drugs that can save their lives?”

TB is the world’s deadliest infectious disease, killing more than 1.6 million people in 2017, according to the World Health Organization. India has the highest incidence of TB, with more than a quarter of all TB cases, including drug-resistant forms of the disease.

In February, Venkatesan and another TB survivor, Phumeza Tisile, filed a patent challenge in India to try to block pharmaceutical giant Johnson & Johnson (J&J) from extending its monopoly on bedaquiline, a critical medicine in the treatment of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). Both women survived DR-TB but lost their hearing because of the toxicity of their treatments. They are now fighting to ensure that newer drugs like bedaquiline—which are safer and more effective—are made more accessible. Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is supporting this patent challenge as it winds its way through the Indian court system.

If India grants the new patent, J&J’s monopoly on bedaquiline would be extended from 2023 to 2027, delaying the entry of generic alternatives. This strategy of “patent evergreening” through filing of additional, often unmerited, patents is commonly used by corporations to extend monopolies on their drugs beyond the standard 20 years.

Access to and affordability of newer TB medicines is crucial at a time when the standard DR-TB treatment used by most countries has a cure rate of just 55 percent. That means that nearly one out of every two people don’t get better even after enduring a grueling treatment regimen: drugs that need to be injected daily and are associated with serious side effects including deafness and psychosis.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has now recommended bedaquiline as a core part of an all-oral treatment regimen for DR-TB, a move that should relegate older injectable drugs to options of last resort. However, the medicine can only reach the people who need it if J&J prices it affordably and registers it widely—or stops standing in the way of other manufacturers that want to make cheaper generic versions.

In April, dozens of protesters from MSF-USA gathered near J&J’s corporate headquarters in New Brunswick, New Jersey to demand a response: “Hey J&J, make this drug $1 a day,” shouted Sharonann Lynch, HIV & TB policy advisor for MSF’s Access Campaign. Lynch, using her resonant voice honed by years of activism, energized the crowd and drew attention from J&J shareholders arriving for their annual meeting. “Pills cost pennies. Greed costs lives. Can you hear us?” she bellowed.

J&J currently sells bedaquiline for $400 per six-month treatment course to countries eligible to buy the drug through the Stop TB Partnership, affiliated with the United Nations. J&J has not disclosed prices for the drug in other countries. As of November 2018, only 28,700 people had received bedaquiline worldwide since it was approved for use in 2012, which is less than 20 percent of those who could have benefitted from it.

Researchers from the University of Liverpool have calculated that bedaquiline could be produced and sold at a profit for much less—as little as 25 cents per day if at least 108,000 treatment courses are sold per year. At $1 per day, the price would be $600 per person for the 20 months of treatment that many DR-TB patients require.

Bedaquiline was the first DR-TB drug to be developed in more than 40 years, and its development benefitted from considerable public investment. Evidence for the drug’s potential to improve cure rates with fewer side effects was also the result of joint efforts by the global TB research and treatment provider community.

MSF is one of the biggest non-governmental providers of TB care worldwide, especially for drug-resistant TB. Operational research carried out by MSF and others was key in generating evidence of bedaquiline’s effectiveness against drug-resistant forms of TB. Additional clinical trials by MSF are underway that could further inform treatment options containing the drug. Despite these joint efforts, J&J sets the price for bedaquiline at its own discretion, effectively deciding who can have access.

“It’s not complicated: drugs like bedaquiline that are created and developed together with the global TB community and using public money should be available to people who need them at the lowest possible price,” said Lynch. “The public has already paid for this drug. It’s time the public has affordable access to it.”