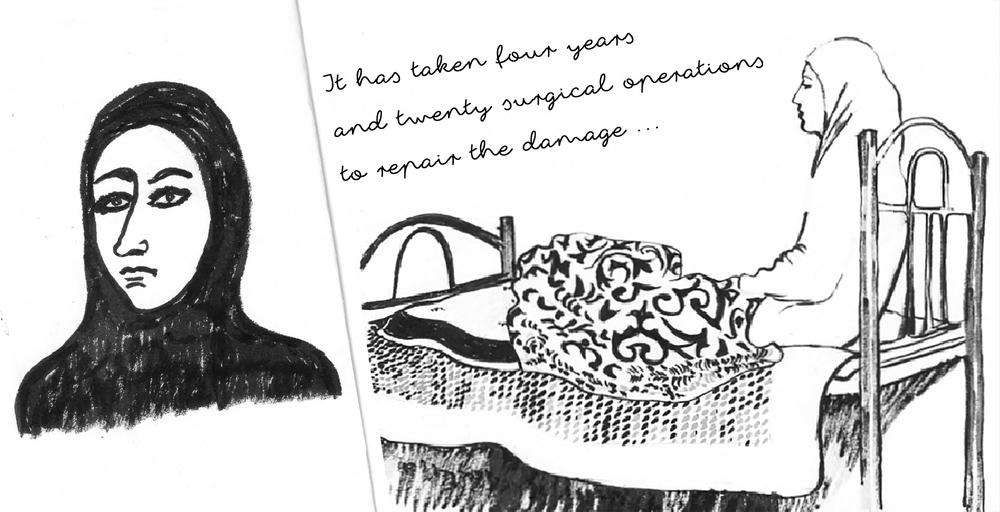

Residents of besieged Eastern Aleppo have been told to leave their homes or face death. As they brace themselves for what comes next, Amal Abdullah recalls the day four years ago when she was told to leave the eastern Aleppo neighborhood she grew up in, and the damages she faced even after relocating to escape the dangers of war.

It was mid-July 2012 when the authorities told us we should evacuate our neighborhood in east Aleppo or face the consequences.

All my life I had lived in Aleppo; life there was beautiful. People helped each other, there was freedom, the economy was thriving. I was 32, I lived with my parents and siblings, and worked in a shop in a mall.

But then the war began and everything changed and we lost the life we had.

When the authorities told us to leave our neighborhood, Salaheddine, some people believed them, but others said, “No, we won’t be bombed.” Many didn’t want to leave their property, others didn’t know where else to go. My family [and I] moved to Al Kalaseh neighborhood, in central Aleppo, where we had relatives. But my father stayed on alone [to live at our home].

Every once in a while, I went back to Salaheddine to see my father and pick up a few clothes, but it was risky. There was bombing and ground fighting going on, with few cars in the streets, and no electricity, water or communications.

Al Kalaseh, by contrast, was quiet and peaceful at first. It’s a neighborhood in the heart of Aleppo, near the citadel and the main vegetable market. It wasn’t 100 percent peaceful—we heard helicopters and planes in the sky —but for those weeks, we carried on pretty much as normal. We socialized, we had family gatherings at my aunt’s house, I went to the dentist.

On the evening of August 1, 2012, my cousin [and I] were walking home when suddenly a bomb fell close by. I saw the flash and heard the explosion. We were pulled into a building by strangers, but we decided to make a dash for it to a relative’s house nearby. As we were running, a second bomb fell in between two buildings. The street was filled with panic. People were running and shouting and there were wounded people on the ground. Again, strangers pulled us indoors and we sheltered in an apartment on the first floor.

People were lighting candles. I sat down on a sofa to wait it out. Members of my family called me five or six times in a row, asking me where I was and saying that the situation was getting worse.

The next moment I saw a strong light and heard a loud explosion. I was fully conscious and screaming, but I didn’t feel any pain. The woman who had been standing next to me was on the floor, dead. I was rolled onto a blanket and carried downstairs. I heard people calling for an ambulance.

In the ambulance, men crowded around me, asking questions: What was my name? Who were my family? Where was my mobile phone? They couldn’t find my phone, but I managed to tell them my sister’s number. When she picked up the phone and heard my name, she thought I was dead. But I wasn’t dead, I was just badly injured.

Life After the Bombing

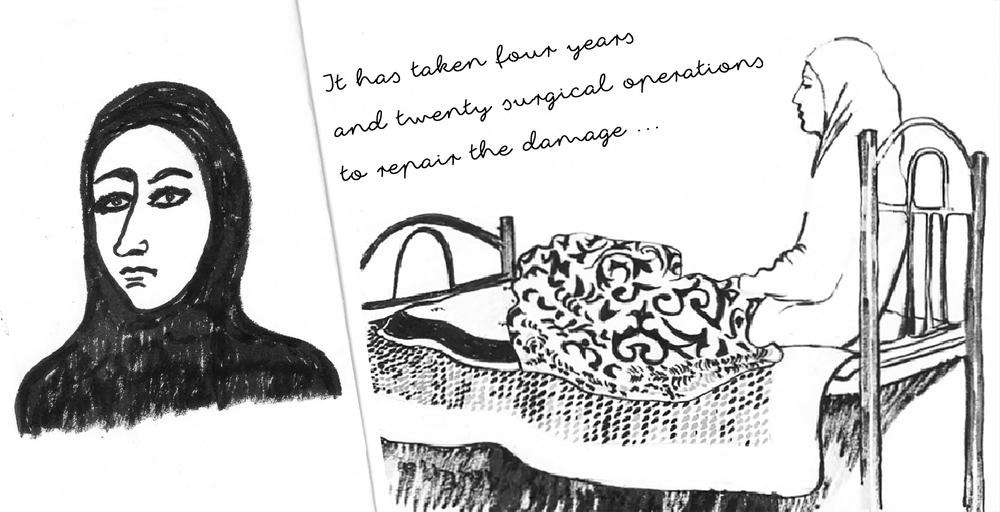

In Abdul Aziz field hospital, they gave me an anesthetic and tried to stop the bleeding. The force of the explosion had thrown me against the wall, smashing the bone in my elbow. My leg was almost severed by shrapnel, and I had shrapnel wounds in my hand, arm, chest, ribs, and abdomen.

I was transferred to Al Razi public hospital. It was a hectic, dangerous journey; there was shelling going on and I was still bleeding. The whole area was being bombed. They carried me straight into the operating theater, and the last thing I remember was the surgeon asking me to recite a verse from the Quran as the anesthesia kicked in. They operated on me for 10 hours—from 10 that night, until eight the next morning—and I was unconscious for five days.

When I was discharged from hospital, there was no safe place to go. I had a severe bone injury, but the main problem was the fear. Every time I heard airplanes in the sky, the pain got worse.

Every day and every night we heard bombs, and a stray bullet landed in the garden, injuring my sister. There was no electricity and no communications. I kept on having flashbacks to the day I was injured. After a month, we managed to leave the city and escape to Jordan.

In the four years since I was injured, I’ve had 20 surgical operations to repair the damage to my leg, arm, and hand. After a year of bone grafts and follow-up care in MSF’s [Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières] reconstructive surgery hospital in Amman, I’m almost ready to be discharged. I walk with crutches, but I’ve got an artificial joint in my hand, so I can move it freely now.

Now I look at what’s happening in Aleppo—the bombings and the siege— and feel for the people left there. I remember how it feels to live in danger, when it’s too risky even to move around. If only no one else in Aleppo had to go through what I’ve been through.

For me, my hope is just to be like any normal girl, to have a life like I had before. Sometimes I feel sad when people ask, “What happened to you?” But this is destiny; I have to accept it. I feel lucky for having had such good medical care, and I just hope to make a full recovery.”

Names have been changed at the patient’s request.