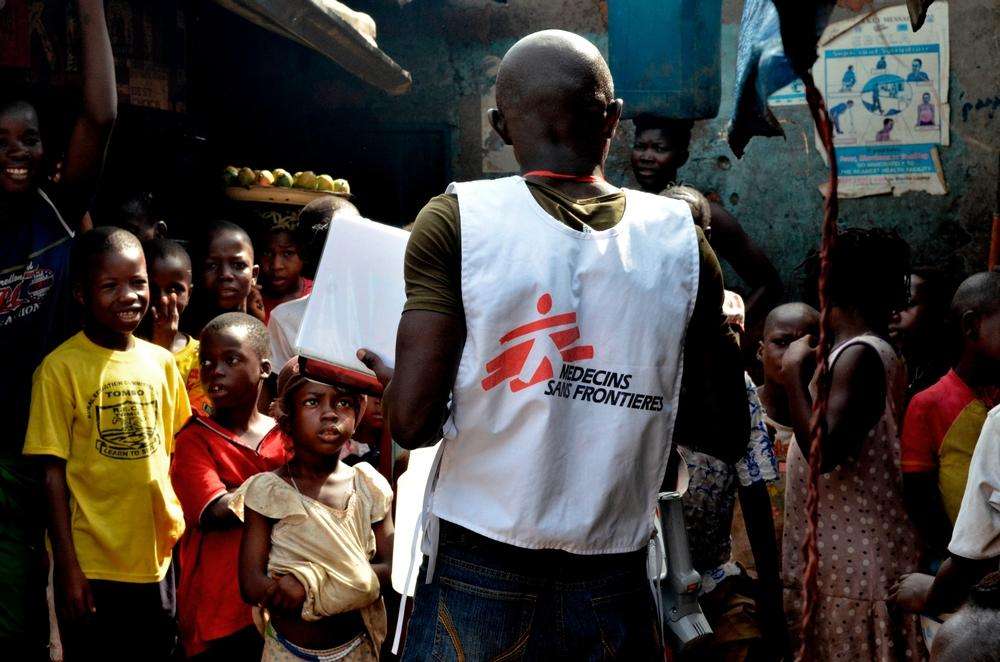

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) health promoters go into the high-risk areas of Freetown, Sierra Leone, to educate communities to recognize and prevent Ebola. They also perform the delicate task of supporting survivors and families of Ebola’s victims.

Just in front of the Prince of Wales school, a custodian scolds seven-year-old Mamadou for being late on his first day. In any other place, it could be a normal exchange, but in Freetown there is an added meaning. After six months of interruption due to the Ebola outbreak, schools have just reopened, and the bustle of children in their colorful uniforms lends a happy chaos to the streets of the city.

The Prince of Wales school has been the center of MSF activities in Freetown for the past five months. On the grounds of the school, where the Ebola management center was built, MSF workers fought against the disease, hoping to see this moment: when the Prince of Wales was once again a place for children.

“The situation is improving in Sierra Leone, but there are still new Ebola cases almost every day,” says Fran Miller, MSF’s head of mission. “This is why we focus our activities in the communities, to identify and respond promptly to every new case, while continuing to inform the population about the importance of remaining vigilant.”

Sending the Right Message

For MSF’s work to be effective, the community’s participation and understanding are crucial. Though every radio station broadcasts health messages about Ebola and there are posters on every street corner, denial and fear are still prevalent among the population. That's why MSF teams conduct health promotion activities in the most dense and complex areas of Freetown, educating the communities on how to prevent the spread of the disease.

“Our work is not just to inform,” says Kim Federici, MSF’s health promotion manager in Freetown. “We also build knowledge and trust, we have dialogue with the communities, and sometimes we advocate for them.”

“Explaining how to react to a suspected case of Ebola requires the capacity to empathize with the community, to understand their fears and problems, and to adapt the message to the context,” Federici continues. “This is where our national health promoters, with their in-depth knowledge of the communities and their emotional intelligence, are so important.”

Musa Tary is part of MSF’s health promotion team in Freetown. As he walks through the city’s slums, he is well aware that the risk he is taking is extremely high. “When we go into the heart of a community, we don’t have any personal protective equipment (PPE) to protect us,” he says. “In the hotspots, we just don’t know what we will find. We interact with the community in a very intimate way; we play with children, we talk with potentially high-risk contacts, and at any moment someone could just touch us and say ‘I am sick, help me.’”

Healing the Wounds Left by Ebola

Health promoters do more than help communities identify, prevent, and respond to the disease. Along with mental health counselors, they fight stigma and offer psychological support to survivors and the families of Ebola victims in the communities. “Some people have been stigmatized for having survived when other family members died,” says Patrick Sam, a schoolteacher now working as a mental health counselor for MSF. “In other cases, we face social and economic problems. Ebola has destroyed entire families, leaving widows, orphans, [and other] people without any income and only the support of their families and their communities.”

Patrick spoke with Aissatou, an Ebola survivor, outside her mother’s house. Aissatou was discharged from the Prince of Wales Ebola management center on February 4, along with her 14-year-old daughter. In the same center, she lost her husband and four other children. “We need to encourage them, to motivate them to start again,” says Patrick. “Sometimes it is difficult even for us to know what to say—there are situations that are far beyond our capacities as health promoters. We can support them, but we cannot fix their problems. Sometimes it is just the communities that can help themselves; sometimes it is just time.”

Before leaving, Patrick asked Aissatou where her daughter was, and if she is well. “She is back at school,” says Aissatou.

Read More: Chasing Ebola in the Slums of Freetown