“I live in the Tse Lowi [camp] with my son and six grandchildren. In February, it will be two years since we had to flee our village,” said Yvonne, in front of the straw hut where she now stays.

“Armed men descended on the village after dark, setting fire to our houses and killing people in a most dreadful way. My son’s wife died that night. They burned down my house and we had no choice but to flee in the middle of the night, taking nothing but the clothes on our backs. We walked for three days and spent three nights sleeping in the bush to get away from the attackers. I was scared. We finally reached Tse Lowi on the third day.”

Yvonne is one of thousands of people displaced by conflict in the Ituri province of Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) since fighting between the Hema and Lendu ethnic groups that gripped this province in the early 2000s reignited in December 2017. She now lives in the Tse Lowi displacement site with her son and six grandchildren. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) estimates that more than a million people have been displaced by the violence since then, although it is almost impossible to know the exact figure due to frequent population movements. Today, some 200,000 people have spontaneously gathered and settled in sites without access to food, water, or medical care. Hundreds of thousands more live with host families.

Inside Yvonne’s hut, one of her grandsons stoked a fire crackling beneath a bubbling saucepan. The hut seems fragile, as if it could go up in flames with the slightest gust of wind. The straw structure is now home to eight people, for whom it serves as both kitchen and bedroom.

Massive displacement

Dozens of makeshift camps like this one have sprung up in the hills of Nizi. They can be seen from each bend of the dusty roads winding through the region. The structures on the newest sites are just straw huts like Yvonne’s, while the more established settlements have some sanitary facilities such as toilets and sometimes plastic tarps to protect the shelters from the rain.

The most fortunate people live in buildings built by humanitarian agencies. Still, none of these sites sufficiently meet the needs of the displaced: They lack access to food and clean water and sanitation. Because of these deficiencies, preventable illnesses linked to the poor living conditions—like diarrhea, malnutrition, and respiratory infections and malaria—are common, sickening and killing thousands of children in the camps. According to recent surveys carried out by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), the mortality rate for children under five who arrived to the camps in spring 2019 is three times above the emergency threshold.

Huge Needs for Displaced People in Ituri, Democratic Republic of Congo

Yvonne Buma – Displaced person in Tse Lowi camp

I left the village because

they were setting fire to the houses

and killing people in a dreadful way.

My house was burnt down.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Since late 2017

the northeast of Ituri in DR Congo

has been in the grip of an extremely violent intercommunal conflict

forcing thousands of people to flee their villages

and take refuge in informal camps.

The living conditions in the camps are terrible

and access to safe drinking water, food

and basic hygiene services is limited.

Dikanza – Displaced person in Kambe camp

We've been here since June.

I've been at this site

for 7 months now.

We need food,

water, toilets and showers.

DRC – Nizi – Drodro – Angumu – Lake Albert – Uganda – Ituri province

In some health zones

the mortality rate among displaced and local children

under 5 years of age is 3 times higher than the emergency threshold.

Médecins Sans Frontières

is helping look after the

host communities and displaced persons.

Dr. Aristide Kengni – Paediatric Supervisor, Nizi General Referral Hospital

We are seeing an increase in the number of consultations

due to the presence of large numbers of displaced people in Nizi health zone

and the introduction of free medical care by Médecins Sans Frontières

almost a month ago. MSF is supporting

the community health posts as well as 7 health centres

that refer the most seriously ill children here, for us to treat

their complications, whether they are nutritional or paediatric.

MSF also operates mobile clinics.

Dr. Eddy Kambale – Mobile Clinic Supervisor, Drodro

We're here to support the

displaced people by providing

basic medical care, particularly for malaria, respiratory infections

and diarrhea. Community health workers

refer the cases to us and we treat simple cases

in the mobile clinic or at the health centre.

In addition, MSF is carrying out water supply and sanitation activities

and distributing mosquito nets and essential supplies.

Despite all these efforts to respond to the emergency,

the living conditions of the displaced people are still well below

acceptable standards and the needs remain huge.

A chain of care from the ground up

“When the children get sick, I take them to the community health post in the camp,” said Yvonne.

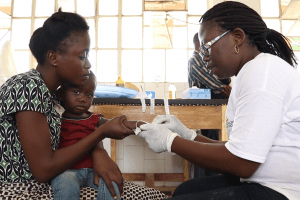

Community health posts have been set up by MSF in 19 of the area’s 24 camps. They are run by community members trained to recognize the most common illnesses. These health workers measure children’s mid-upper arm circumference to test for malnutrition, carry out rapid tests for malaria, and check for fever and diarrhea.

They are equipped with stocks of easy-to-use medicines such as paracetamol and antimalarials to provide initial treatment. If needed they refer sick children to one of seven health centers supported by MSF. An MSF nurse works in each, assisting teams of local health staff.

Seriously ill children are referred to the regional Nizi general referral hospital for hospitalization and specialist care. Here, MSF supports the Ministry of Health’s intensive care and resuscitation unit, the pediatric ward, and nutrition and postnatal units. The goal is to treat children as early as possible to avoid medical complications, but given the huge needs in the region, the 56-bed pediatric ward is often at—or over—capacity.

Growing needs

In Tse Lowi camp, where Yvonne and her family live, hygiene facilities including latrines and enclosed bathing areas have been installed. But many newer settlements, such as the seven-month-old Kambe camp, lack such services. In Kambe, 426 households share just four makeshift latrines, and there is nowhere to shower. Food is scarce, the nearest water source is a 45-minute walk away, and there are few opportunities for work, with most people living on less than a dollar a day.

Since December 2019, MSF has scaled up activities to respond to the needs in the camps. But the current level of assistance is not sufficient, and people are still living in extremely poor conditions. The humanitarian community in Ituri must urgently address this escalating crisis and scale up assistance.

MSF provides medical care, works to improve access to clean water, and distributes mosquito nets and relief items at 34 sites in the health zones of Nizi, Drodro, and Angumu in DRC. We’re also responding to the ongoing Ebola outbreak—DRC’s worst ever—in Ituri and North and South Kivu provinces.