In recent years, Haiti’s capital city, Port-au-Prince, has been convulsed by clashes between armed groups and the police, with no signs of abating.

The violence has increased dramatically in 2024, as armed groups attacked new parts of the city including police stations, hospitals, and residential neighborhoods. This surge in conflict, occurring frequently in residential zones, has deeply affected communities and seriously disrupted the health care system, which is struggling to remain functional amid supply shortages and attacks on patients and medical staff.

The instability has severely disrupted the operations of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams, at times forcing the temporary closure of facilities and suspension of activities. Though we have resumed activities in six medical facilities in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area, the violence continues to rage in neighborhoods, blocking access to health care and putting civilians at daily risk of being killed, injured, or kidnapped.

The conflict has received little international attention, but its impacts are dire and far-reaching. Here’s what to know about the crisis in Haiti and how our teams are working to provide care despite grave challenges.

Facts about Haiti

Background of a crisis

Where is Haiti?

Haiti is a country located on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, which it shares with the Dominican Republic to the east. It has a population of more than 11.6 million people, of whom nearly one-third live on less than $2.15 a day, according to the World Bank.

What are the challenges Haiti faces?

Even before the current conflict, Haiti faced significant challenges as the poorest country in the western hemisphere, with the highest maternal mortality rate. In 2010, Haiti was hit by a devastating earthquake that left an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 dead. It was followed shortly after by a cholera outbreak that killed more than 7,000 people. In 2021, a 7.2 magnitude earthquake caused large-scale destruction to housing and already-fragile infrastructure. The current conflict has only exacerbated these challenges.

A country in crisis

Haiti at a glance

11.6 million people live in Haiti.

5,600 people died from the violence in Haiti in 2024.

Haiti is the poorest country and highest maternal mortality rate in the western hemisphere.

Nearly a third of the population lives on less than $2.15 per day, according to the World Bank.

Why is Haiti in turmoil now?

Clashes between armed groups and the police have grown in recent years as the government has struggled to control many areas of the capital and beyond. After the assassination of President Jovenel Moïse in 2021, the situation has further deteriorated amid a political crisis. By 2023, the homicide rate more than doubled, according to the UN, and the true number of dead is likely substantially higher.

Since February 28, 2024, there has been a surge in violence that has deeply affected communities and has seriously disrupted the health care system, which is struggling to remain functional. The urban environment in Port-au-Prince has transformed, with checkpoints and fortified neighborhoods becoming the norm as residents try to shield themselves from the violence. Since mid-2024, Haitian police have been supported by police from several other countries, led by Kenya.

Risks Haitians face

Each day, people in Port-au-Prince face the risks of death, injury, and kidnapping. The conflict in Haiti killed more than 5,600 people in 2024, according to the UN—up by 1,000 from the year prior, which itself saw a sharp increase in homicides as well as kidnappings. At the same time, public health care facilities are facing regular shortages of staff, medicines, and supplies, impacting their capacity to respond.

Wisly, a Haitian migrant in Mexico

"Returning to Haiti means death”

“I’m here because I want to go to the United States and help my family,” he said. “In the United States I have family. Here I’m alone. Here there’s nowhere to sleep. Yesterday it rained all day and I slept in dirty water. I don’t want to go back to Haiti. There’s no school there, there’s no food there, there’s no work ... Returning to Haiti means death."

Increasing gang violence

The conflict in Haiti has largely taken place in urban areas, including densely populated neighborhoods in and around the capital This has put the civilian population at high risk of being caught in the crossfire or directly attacked We face this reality daily at medical facilities where MSF works.

Widespread sexual violence

Rapes and other forms of sexual violence have become widespread amid violence and insecurity in recent years. Survivors are in urgent need of safe shelters, mental health support, medical care, and other vital services that are often unavailable due to a lack of resources.

After the assault, survivors face a difficult journey while carrying physical and psychological scars from the incident. Only a few emergency shelters exist for survivors of sexual violence in Port-au-Prince, and they have very limited capacity. Many survivors are forced to live in gathering sites for displaced people, sleep on the streets, or return to the place where they were assaulted. Access to economic or legal assistance is limited, and the ongoing turmoil has made it difficult to seek justice through the legal system or obtain protection from the authorities.

A survivor's journey to recovery

To highlight the crisis of sexual violence in Port-au-Prince, MSF partnered with an award-winning Haitian artist in the US, Lyne Lucien, to animate one survivor's difficult journey to recovery

Medical and psychological services should be available at every stage of a survivor's recovery—and timely medical attention is crucial for providing the most comprehensive care possible, including immediate post-exposure HIV prophylaxis and contraception. While MSF has stepped up its response to sexual violence in Haiti, more services are urgently needed within the communities most affected.

Lack of access to health care

Health care services in Port-au-Prince are under severe pressure. The main hospital, L'Hôpital de l'Université d'État d'Haïti, is currently inoperable and situated within one of the conflict zones. Other hospitals are facing similar challenges or are overwhelmed with casualties, limiting their ability to accept new patients. Even MSF’s Tabarre Hospital, which specializes in trauma and burn care, is often at capacity, forcing it to focus only on the most severely wounded patients. Last year, in May alone, more than 30 medical centers and hospitals shut their doors—including L'Hôpital de l'Université d'État d'Haïti—due to vandalism, looting, or being located in insecure areas.

In addition to those wounded in the violence, people with chronic illnesses, such as tuberculosis and HIV, are at high risk due to the lack of access to medical services and lifesaving medications. Unsanitary conditions in displacement sites have spread across Port-au-Prince, heightening the risk of waterborne diseases like cholera.

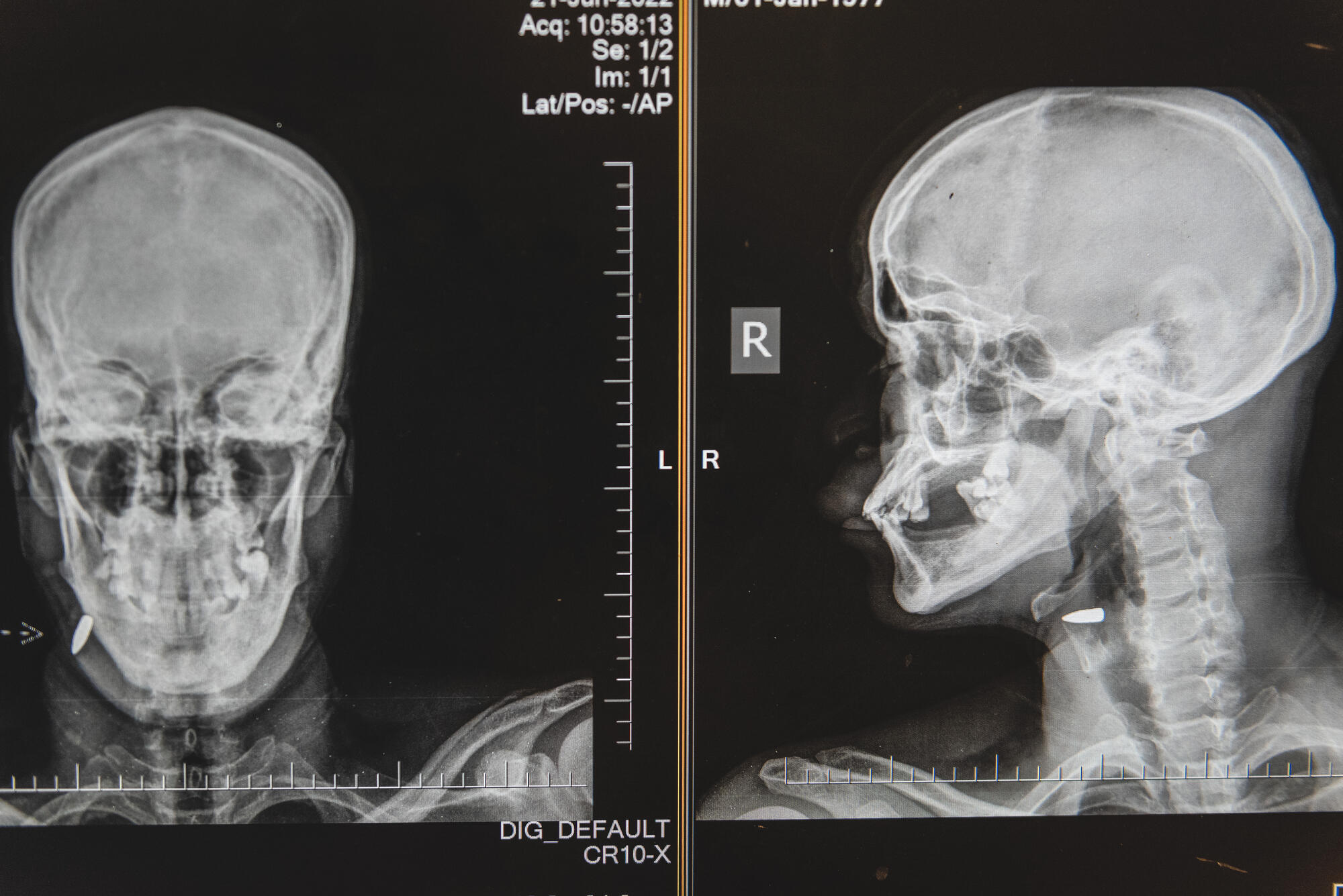

From left: A young girl wounded by a stray bullet on her way home in Fontamara. Haiti 2022 © Johnson Sabin; Claudette's leg was amputated at MSF's Tabarre Hospital after having complications from a bullet wound as a result of not being able to reach a health facility in time. Haiti 2022 © Alexandre Marcou/MSF

Attacks on medical staff and patients

In the fall of 2024, a string of attacks and threats by police and vigilante groups against MSF staff and patients led to a temporary suspension of activities. After 22 days, we were able to partially resume activities in the Port-au-Prince metropolitan area. However the threat of violence remains a serious concern impacting the ability to provide care.

Timeline of attacks

MSF staff and patients have been subjected to a string of attacks in Haiti in recent months.

An MSF ambulance carrying a patient in critical condition in Port-au-Prince was stopped by police and detained, preventing our team from providing the necessary care. After being held for over an hour, the patient died before they could reach a hospital.

MSFAt least two patients were executed after the police stopped an MSF ambulance in the Drouillard area of Port-au-Prince. MSF staff in the ambulance were violently attacked, threatened, and held against their will for more than four hours before being allowed to leave.

Two MSF ambulances were stopped by officers of the Haitian National Police’s Brigade de Recherche et D’Intervention (BRI), who threatened to kill MSF staff in the near future.

In Delmas 33, one of our drivers was verbally assaulted by plainclothes police officers who warned us of future attacks on our ambulances.

Shortly before midnight, another MSF ambulance transporting a patient was stopped near Boulevard Toussaint Louverture by a SWAT team who threatened to kill the patient on the spot. After intense negotiations, the ambulance was allowed to continue its journey to the MSF hospital in Tabarre.

In Carrefour Rita, a Haitian National Police vehicle driven by a plainclothes policeman armed with a pistol stopped an MSF vehicle taking staff to the workplace. He threatened the MSF staff members onboard, saying that next week police forces would start executing and burning our staff, patients, and ambulances.

Shortages of medical and humanitarian supplies

The insecurity in Haiti has disrupted supply lines, leading to the closure of the airport and seaport and critical supply shortages in health facilities. In February 2024, the deteriorating situation caused a nearly three-month pause in the delivery of humanitarian and medical supplies. This supply shortage forced MSF’s general hospital in Cité Soleil to cut outpatient consultations by half in April.

“If we do not receive our medical supplies in the next two weeks, we will be forced to drastically reduce our operations," said Mumuza Muhindo Musubaho, MSF head of mission in Haiti in May 2024. "We had to increase our capacity to cope with the influx of patients, but unfortunately, the enormous consumption of medications means that we are currently in short supply.”

Finally, in June, MSF was able to successfully deliver 80 tons of much-needed medical supplies to Haiti, allowing our teams to resupply programs.

Our response to violence in Haiti

As Port-au-Prince endures these turbulent times, MSF continues to provide care and support to people impacted by the violence. Our teams deliver a range of medical services throughout Haiti, including general health care and treatment for burns, trauma, and sexual violence. Our facilities include hospitals in Tabarre and Cité Soleil, a sexual violence and reproductive health care clinic in Delmas, and an emergency and stabilization center in Turgeau. We also support health centers and have operated mobile clinics in the most affected neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince as well as sites where people have gathered after fleeing violence.

Emergency response

In the two months following the escalation last February, our teams across Haiti provided 9,025 outpatient consultations, treated 4,966 urgent cases including 869 bullet-wounded patients, cared for 742 traffic accident victims, and admitted 99 severely burned patients at Tabarre Hospital, half of whom were children.

Care for survivors of sexual violence

In 2024, MSF provided care to 4,463 survivors of sexual violence at Pran Men'm Clinic and Carrefour Maternity Hospital, and through a new program at the hospital in Cité Soleil. Our teams also provided care to survivors through mobile clinics in multiple areas of Port-au-Prince.

Maternal health

With a maternal mortality rate of 5.3 and a neonatal mortality rate of 2.4—the highest in the western hemisphere—the need for maternal and neonatal health care is dire in Haiti, including areas outside of Port-au-Prince that were severely damaged in the 2021 earthquake. One of those areas is Port-à-Piment in southern Haiti, where in 2023, MSF reopened a hospital for maternal and neonatal health after rebuilding and upgrading it. The hospital now offers surgery for patients with obstetric complications as well as pre- and neonatal care. However, many other facilities in the area were never properly repaired, so access to health care remains limited for pregnant women and newborns.

Water and sanitation

MSF also provides water and sanitation services, including latrine installation in sites for displaced people and health and promotion of hygiene awareness.

Claudia, MSF nurse at Turgeau Emergency Center

"We give our all to save lives"

"Every day is unpredictable; this morning, for example, I arrived and everything went relatively smoothly. There were no problems on the road, it was just routine. Why do I say routine? Every time there's a bus on the Martissant road, we have to stop to give money to an armed group, and then they let us go. We shouldn't have to adapt to this kind of life, but unfortunately, we're in Haiti, trying to survive.

"I arrived at the emergency center at 7:45 a.m. and, as a nurse supervisor, I had to organize the day. Like all week, there were a lot of children in the waiting room, because we're overwhelmed with pediatric cases. There are six beds for children, and they were already full, so we had to get organized. We have to adapt every day to the influx of children."

Where we work in Haiti

Facility | MSF services |

|---|---|

| Turgeau Emergency Center |

|

| Tabarre Hospital |

|

| Drouillard Hospital |

|

| Carrefour Hospital |

|

| Pran Men'm Clinic and Carrefour Maternity Hospital |

|

| Isaïe Jeanty Maternity Hospital |

|

We speak out. Get updates.

*Name changed for confidentiality.