Since 2022, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working with Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities in Alto Baudó to bridge cultural gaps in order to improve access to the health care MSF provides. As part of the initiative, MSF collaborated with photographer and documentary maker Fernanda Pineda and local communities to produce "Riverographies of Baudó", a photography project highlighting the scars of conflict, institutional gaps, and the work of women healers, herbalists, and midwives.

Yazury Dumaza, who is a member of the Emberá community and an intercultural mediator with MSF in Alto Baudó, was part of the production team. Here, she reflects on the experience as well as her own background as a member of one of the Indigenous communities impacted by this crisis.

I was 4 years old when I saw a camera for the first time.

It was in 2003, in the municipality of Bojayá, Chocó department, where my family and I were forcibly displaced from our home in the Emberá Dóvida Indigenous community of Charco Gallo because of armed conflict. Those were very difficult and violent times, during which we were displaced seven times. We settled in Bellavista, in the center of town, an hour away from my community, and my mother wanted us to have a family photo. We went to the riverbank to look for the only man who took portraits, and I was so excited for the photo that, at the moment they took it, I fell into the water and came out completely drenched!

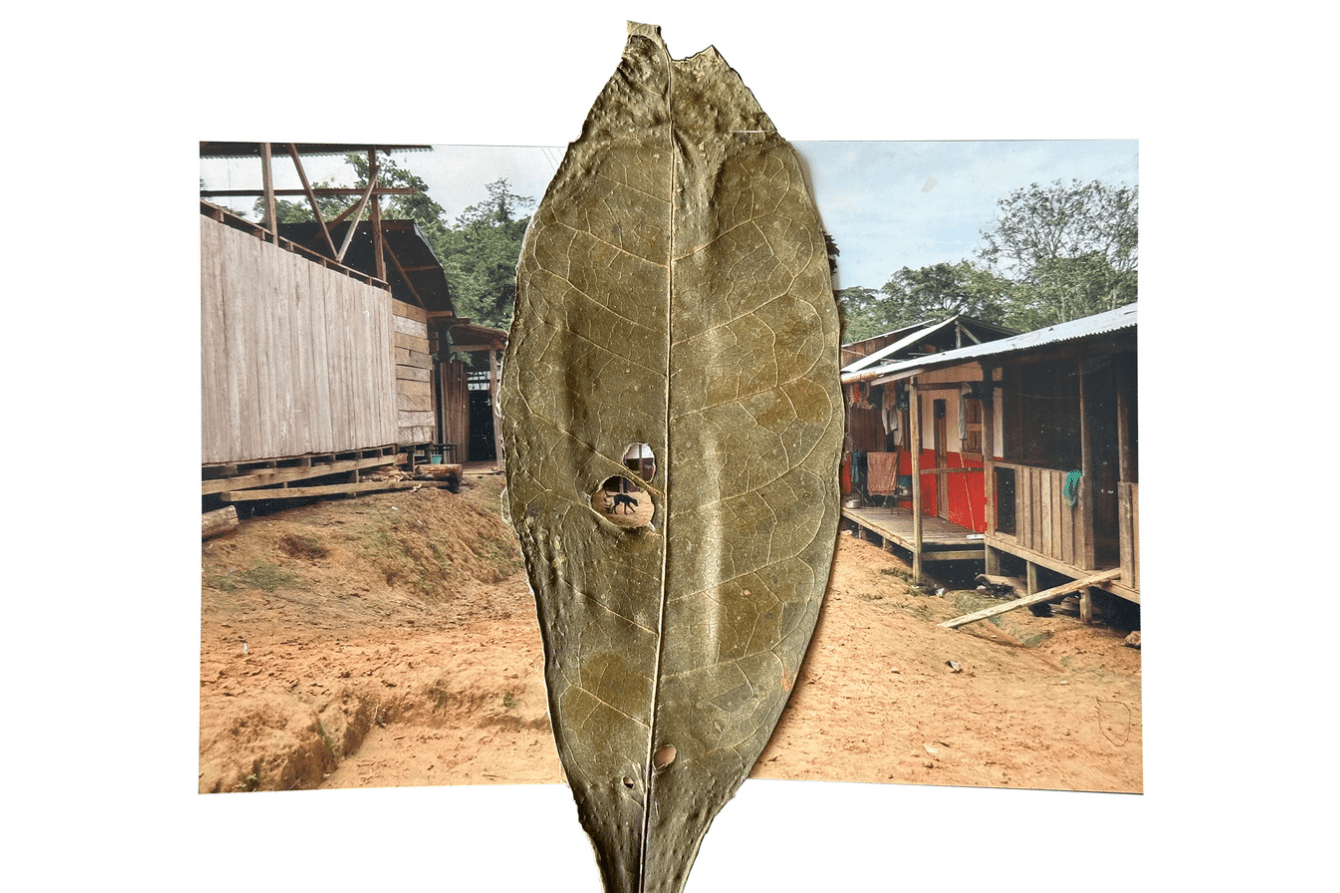

Rogelina Arce, in Puesto Indio, symbolically heals a photo of the community's main street with totumo leaves, which are often used to heal pain during childbirth. Colombia 2024 © Yazury Dumaza/MSF

Today, 21 years later, I have a camera in my hands. I work as an Indigenous intercultural mediator for MSF in Alto Baudó, Chocó, where the main focus of my role is to interpret between MSF staff and Emberá community members during consultations, trainings, and health awareness sessions. But this time I had the opportunity to unite a personal passion and my work: I visited two Afro-descendant villages and one Indigenous village to participate in a photography project.

Fernanda Pineda, a photographer and documentary filmmaker, designed a workshop in which nine colleagues from the MSF engagement team and I learned elements of photography, asked ourselves questions about the ways in which Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities are represented publicly—almost always from a victimizing perspective—and considered other ways our stories could be told.

Then, along with Fernanda and three colleagues, we went to Chachajo and Mojaudó, Afro-descendant villages, and Puesto Indio, an Indigenous village, to talk about the forced confinement (the armed group’s strategy to exert control over remote territories) from a different perspective: one that would take into account the voices of women, of those who are living the consequences of the conflict, and who continue to keep the communities healthy.

Fernanda proposed to work with the healers and midwives in these villages who are caring for their communities with traditional medicine. We asked them to tell us about the places most damaged by the violence. We took photos of those places, printed them, and then each woman healed the pictures, in a symbolic way, with her plants and sutures.

The power of photographs

The first time I took photos was with a phone, when I left Chocó to visit a major city: Medellín. I was 9 years old, full of excitement to take many pictures and show them to my uncles, parents, and all the people around me. I really liked that all the photos would capture a memory. Since then, I have enrolled in photography workshops and courses and through my photography, I have tried to show from the territory who we, the Indigenous communities, are. I now think that the photos I’ve taken—both during this project and otherwise—are more than a recording of a memory. I hope these photos can reach people far and wide, so that more people know what is happening in Alto Baudó and that those who have the power to change something are moved to do so.

During this project I heard comments from community members that have become familiar phrases to me in the course of my work:

“I cannot go fishing.”

“I cannot go hunting in the mountains.”

“Sometimes we prefer to go hungry, I am afraid to go to the mountains or that a mine will kill me.”

“We do not sleep well here.”

These challenges they speak of all affect the practice of traditional health because sometimes the jaibanás (Emberá spiritual healers) and the midwives do not have the tools they once had to heal. Formal health care is almost never an option for people in these communities, because it is often very far away and because western doctors usually discriminate against Indigenous people.

In the last two and a half years, in my work as a mediator between the Emberá communities and MSF professionals, I’ve supported MSF’s training of community agents in basic health, noticing warning signs in patients, and in managing referrals of patients for care. This training has supported more than 2,000 referrals of patients to medical centers. On several occasions, I have helped MSF colleagues understand the condition of a patient in a remote location, so that our boat could arrive quickly to take them to a medical center. This included cases of people with injuries, snake bites, and risky pregnancies, all of which needed urgent attention.

In this photography project, we wanted to show the limitations that the communities experience, but we also wanted to highlight that communities have their own forms of healing, which are also very valuable. The wise women showed us that what one sees as incurable can be healed.

I do not want people to be left with the image of Chocó that is always shown in the news, where people are trapped in pain and do not come out of it. I want them to see that despite the evils its people are subjected to, Chocó is more than a territory of victims.