It is very early in the morning when a car leaves the Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) base in Bambari, Ouaka region, in the center of Central African Republic (CAR), a country burning itself up with violence. The MSF team is heading to Yamale, a small village in the bush some 19 miles from Bambari. It isn’t far, but the trip takes two hours in the rainy season, as the road is thick with mud.

Villages like Yamale have been the target of unremitting violence at the hands of armed groups and lawless gangs. “I am still scared,” says Musa, a farmer from Yamale. “After the fighting, they broke down the door of my house and stole everything I had. We spent three months in the bush. My children fell ill.”

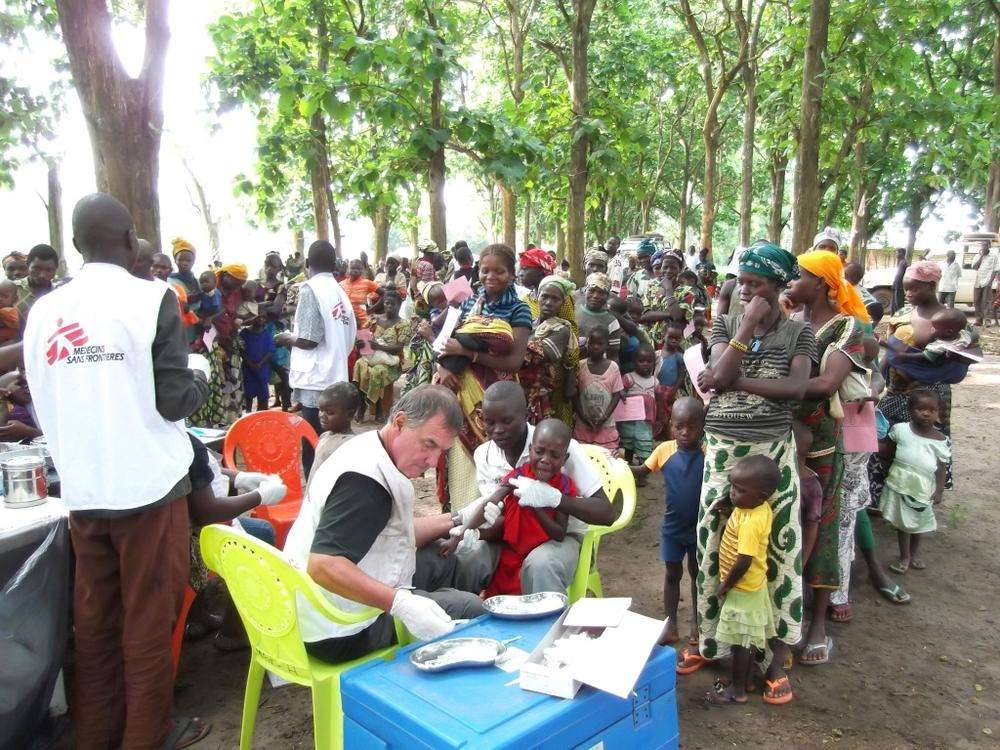

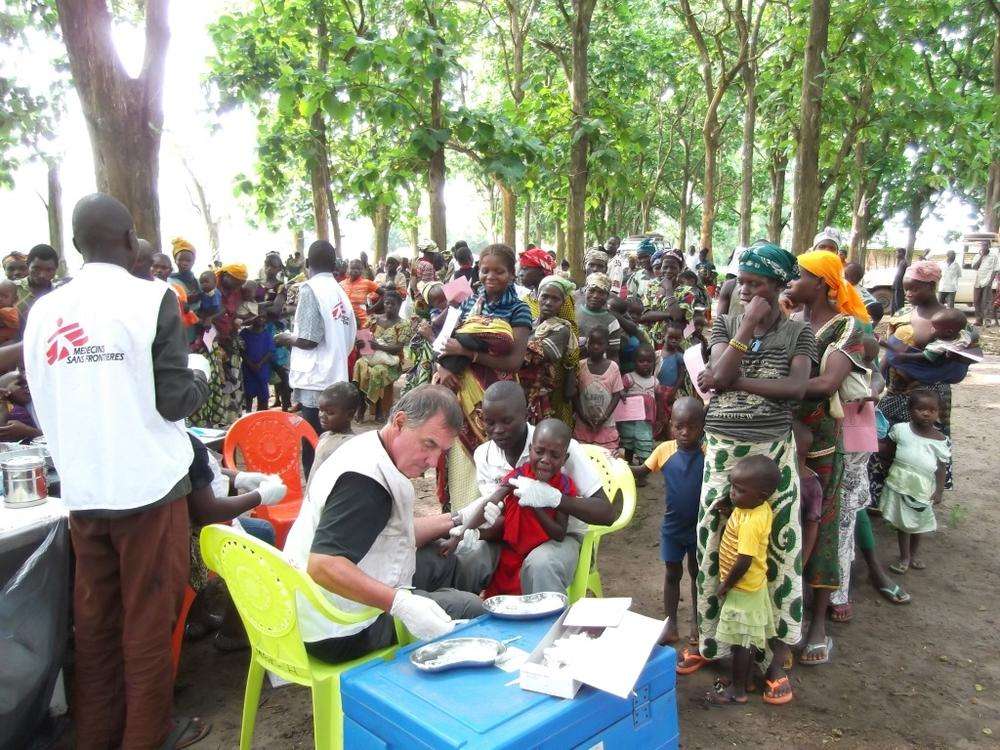

Some villages have been burned to the ground; others are in ruins. Often people have nowhere to stay but in small huts dotted around the surrounding fields. In some villages, the houses are still standing, but often the health center has been destroyed. MSF teams are running mobile clinics to reach the villagers, many of whom are still living in the bush, too fearful to return to their homes.

“They are often so scared that, after we give them their medications, they run back into the bush to hide,” says Dr Robert Ponsioen, MSF’s project coordinator in Ouaka region. “A minute after we have finished, sometimes there is no one left in the village. People run away. Any car passing by causes panic. People are so afraid. We have found ghost villages where there are no people left.”

Traveling by car makes reaching the most vulnerable communities a challenge—not only because of the violence, but also due to the poor condition of the roads. For security reasons, MSF’s six-person team needs to be back in Bambari before sunset, and with all the traveling time, this means five hours of non-stop consultations.

But it’s worth it. A day in the bush for MSF’s team represents access to health care for up to 500 people. People wounded in the ongoing violence are the first to receive attention. Minor war wounds are treated on the spot, while those with more serious injuries are sent to hospital for specialized care. “Recently, we were going along the road and found two women with severe wounds to the leg; one of them had a baby with her,” says Ponsioen. “The bones of one woman’s leg were completely shattered. We took them to Bambari hospital and sent them to the capital, Bangui, the next day.”

At the same time as running the mobile clinics, MSF teams distribute mosquito nets and plastic sheeting to every family, many of whom are living in the open air, under trees. In the rainy season, the bush is a perfect breeding ground for malaria-carrying mosquitoes. All patients are given a rapid test for malaria, which takes about three minutes. Up to 90 percent of them test positive, and are given an oral drug, to be taken over three days, as well as paracetamol for the fever.

Because of the poor living conditions and lack of medical care, conditions like pneumonia, diarrhea, conjunctivitis, and skin infections are all common. To avert the risk of infectious diseases breaking out in these communities, MSF teams have carried out a vaccination campaign in August in the Ouaka region, vaccinating 4,000 children under five against measles and polio.

Mobile clinics are a simple tool but they are not enough: MSF has installed permanent points ("Palu Points") in the villages, where local staff are testing and providing treatment for malaria seven days a week. Most patients seen in the mobile clinics are women and children under five.

Elderly people with chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart problems, are harder to treat. The health needs of people in these communities are huge, and so are the challenges in providing health care. Far from the main towns, thousands of displaced people are struggling to survive.

MSF teams in Central African Republic have been providing health care through mobile clinics to vulnerable communities in the Ouaka region since April, first in Grimari and then in Bambari. Since then, MSF teams have treated 4,639 patients and stabilized and treated 153 people with violence-related injuries.