By Victor Garcia, former MSF Project coordinator in Norte de Santander department, Colombia

Victor Garcia, former MSF Project coordinator in Norte de Santander department, Colombia

It isn't easy to talk about a conflict as complex as Colombia's or about the suffering it has brought to the civilian population for over 40 years, not to mention the enormous economic resources it consumes—and this in a country that is to a large extent prosperous, with abundant natural resources.

However, I will attempt to describe an average day at a health clinic run by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in the Catatumbo region of Norte de Santander as part of the experiences I have lived in one of the most conflict-filled and isolated regions in Colombia. I worked there for a year, from March 2006 to March 2007, coordinating an MSF team. I am writing from memory, so please forgive me if what I come up with is somewhat disordered or if things slip my mind—El Catatumbo is something like that too.

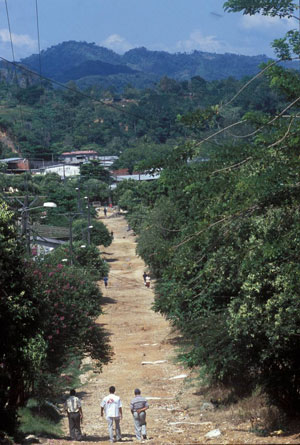

An MSF aid worker and others walk to into the northern Colombia town of La Gabarra. © Jesus Abad Colorado

It is six in the morning. Today, I am getting up a little earlier than usual because we are doing a health clinic in Caricachabokira, and since we never know what we'll come across on the road, it's better to leave earlier.

Caricachabokira is a community inhabited by the Bari indigenous people. The Bari, who once lived in what is now Norte de Santander— a northeastern department (similar to a state) of Colombia—and a large part of Venezuela, have seen their land reduced to just two small reserves: the one we're going to today, and another that is more to the north in El Catatumbo. In Bari, Catatumbo means "god of thunder" and the frequent electrical storms here are truly spectacular, beautiful, and dangerous. Because there are many lightning bolts, it's no surprise that sometimes people are struck. Babido, the outreach worker at the Ikiakarora health post, told me how a lightning bolt had struck inside the health post while he was sleeping and how he had escaped harm because he was sleeping in a hammock that was not in contact with the ground.

In this rural jungle region that is difficult to access, the Colombian government only keeps watch over a few villages that are on the coal highway or that have significant oil resources (Venezuela's Maracaibo oilfield is not far away). The rest is the territory of the various guerrilla groups. There are also paramilitaries who, although officially demobilized, are said to be moving about the area.

Because this is a border zone that is quite rich in natural resources, it is a strategic area coveted by all the armed groups. All are fighting for control of the territory. With its turbid rivers, abundant jungle vegetation and mountains, Catatumbo is considered to be a natural park, although you will certainly not find a single tourist in the area. Let's go on.

We chose Caricachabokira to work in because it is a protected indigenous area and, in theory, there can be no military presence or fighting here. It also has infrastructure, however minimal: a house with an uralite roof that serves as a health post, though without a doctor or a nurse. In reality, our main reason for getting involved in this zone is that we have found many people spread out across small villages who were living without any type of medical care. The closest hospital was, in many cases, several days away on foot, by boat, or by bus. Because of that, people diagnose and medicate themselves. There is much tuberculosis, anemia, leishmaniasis, malaria, hepatitis, diarrhea, low vaccine coverage, and many mental health problems caused by the violence of the conflict. There was no other organization working in this area except some Catholic nuns who live with the Bari and with whom we have always had a good relationship. They looked after educating the Bari girls and boys.

When I arrive at the office, the logistics team is already loading the material that we are going to use during the weeklong health clinic: medicine, laboratory material, portable refrigerators for the vaccines, food, the electricity generator, and each of our personal knapsacks. Before leaving, we have to look into security in the area and on the highway we are going to take.

Mothers with their children wait to be seen by an MSF doctor in Colombia. © Jesus Abad Colorado

We are mainly interested in what is happening in the streets. A few days ago, they blew up a section of the oil pipeline. It wasn't reported in the press, but people knew. Today, things seem quieter and at the bus station, they tell us that from here to where we take the boat, there is normal bus traffic. We start up the off-road vehicles. Vallenato, which is typical Colombian music featuring the accordion, is playing on the radio.

The highway is paved only as far as the oil refinery. The rest is a mud road with holes carved out by the rocking of trucks, which are often loaded with soft drinks and move in fits and starts, blocking the road in both directions. The vehicles get stuck in the mud and unstuck, then stuck and unstuck again, in the weary and moribund rhythm in which things move here. In the rainy season, it takes us between 4 and 13 hours to do 70 kilometers (44 miles). The access road is supposedly controlled by the government, but once on it, any group can stop you. We arrive at La Gabarra where the Bari should be waiting for us with their boats to take us up to the community.

At one point, we can see an anti-aircraft missile fired from the ground that one of the helicopters dodges just a moment before impact. It is a fight between the soldiers and the guerrilla forces. Meanwhile, the Bari are at their activities—fishing in the river, hunting in the woods, collecting cacao or firewood, moving about—and the patients arriving from other places seem more or less calm—the fighting is relatively far away and it is more dangerous for them to return than to stay put.

– Victor Garcia

La Gabarra is a village on the banks of a river. It is a community of about 15,000 inhabitants who have been and who continue to be heavily affected by the violence. It takes just one visit to see that something is happening. Nobody sees, hears, or says anything, as though the whole world were blind, deaf, and dumb.

Many houses have spray paint on their façades. One morning, large and sinister numbers appear inside a circle. Those numbers mark the houses where paramilitaries were living and that are now vacant. The village was a sort of remote port to which people would come to spend the money they earned from coca harvests, spawning an entire business of bars, pool halls, shops, organized crime, informers, and prostitution. There are also people who have tried to stay out of it, but that is difficult because coca seems to be everywhere.

Today, the situation has improved somewhat with the demobilization of the paramilitaries, and the people seem to have a little more zest for life. In La Gabarra, we've treated people with sexually transmitted and reproductive diseases, as well as mental health problems because the aftermath of massacres and threats is often fear, depression, and anxiety. There is also group work with boys and girls to show them that another culture exists—not just the culture of violence. However, the people still live in fear of being pinpointed and accused of collaborating with one side or the other. The work here is slow.

An MSF aid worker speaks to children in Colombia about the medical and counseling services available to them through MSF's fixed and mobile clinics. © Jesus Abad Colorado

As expected, the Bari have not arrived at the port at the scheduled time. Theirs is a different time—they march to a different beat. While we wait, we eat some rice with beans and yucca and drink hot lemon. The heat is heavy, but the Bari finally arrive. At least this time they didn't break the motor by filling the boat with bananas. We greet one another, fuel up, load the equipment, and head upstream.

The river flows dirty and turbid. Every time I travel on it, I imagine that it is even dirtier underneath because of all the bodies that were thrown into it during the big massacres of 2002, when the groups were fighting for control of the waterways. The river also survives the oil pipeline explosions that turn its color to black. But the river does not see, hear, or say anything; nor does it complain. It flows in silence as we advance against the current. Here and there, a heron is perched on the riverbank, but mostly what I see are turkey buzzards. In general, there are few animals remaining to be seen.

After two hours of boating, we arrive at the community port where some Bari children are waiting for us. We must walk from the riverbank to the community and carry our things, and finally, we arrive. Before the light fades, we hang our hammocks in a communal hut that they leave for us and have dinner. The light that remains is from candles or from the fireflies playing in the grass.

Getting health care to more rural parts of Colombia can mean traveling in all kinds of conditions. Here, an MSF aid worker and other passengers help push a bus out of a deep rut.

© Jesus Abad Colorado

Beginning early the next day, the sick from neighbouring communities begin to arrive at the health clinic. We offer free medical, nursing and psychosocial consultations, dentistry, as well as vaccinations, and diagnose diseases such as malaria, diarrheal diseases, cutaneous leishmaniasis, and tuberculosis (TB). The order of treatment is always medical emergencies, pregnant women, the elderly and children. There are many patients with tuberculosis, especially amongst the Bari population. We are trying to figure out why it affects the Bari more. Perhaps it is because of their way of life–whole families cook, sleep and live together in a single hut without a chimney. If we diagnose someone who is sick with TB, we offer to accompany them to a city where we facilitate with the local health promotor, their ongoing treatment through the national TB program. The Bari say that before the Spanish conquistadors arrived they did not have tuberculosis, and see it as normal that five hundred years later another Spaniard should arrive to cure them. I didn't manage to see it, but, in a community in the mountains, they apparently keep a dented helmet, probably from some Spaniard of old, as a trophy.

On the second day of the clinic, from the health post, we can clearly see a military airplane covering two combat helicopters. They fire at and bombard some target a few kilometers away from where we are. We can hear the bombs and the shots, and we can see the smoke. At one point, we can see an anti-aircraft missile fired from the ground that one of the helicopters dodges just a moment before impact. It is a fight between the soldiers and the guerrilla forces. Meanwhile, the Bari are at their activities—fishing in the river, hunting in the woods, collecting cacao or firewood, moving about—and the patients arriving from other places seem more or less calm—the fighting is relatively far away and it is more dangerous for them to return than to stay put. We therefore continue with our activities at the health post. One of the patients says that she thinks the smoke that can be seen is from her house.

Five days later, we have treated an average of 150 patients per day, and we return to the base to do the trip in reverse. The Bari accompany us with their boats. In La Gabarra, another team is waiting for us with the four vehicles, and again there is the muddy road. We get stuck, we get unstuck and we press on. Deep down, that is our rhythm too.

In La Gabarra, we've treated people with sexually transmitted and reproductive diseases, as well as mental health problems because the aftermath of massacres and threats is often fear, depression, and anxiety. There is also group work with boys and girls to show them that another culture exists—not just the culture of violence.

Víctor García