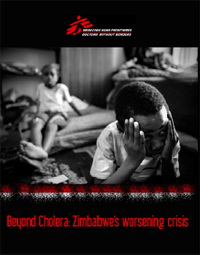

Zimbabwe's political and economic breakdown has led to abysmal access to public healthcare; a collapsed infrastructure; a crushing HIV epidemic; political violence; food shortages and malnutrition; internal displacement and displacement to neighboring countries. Above, more than three million Zimbabweans have fled to South Africa, including these children taking refuge in a church in Johannesburg.

Everyday, Zimbabweans cross the Limpopo River into South Africa, risking their lives to flee their country. An estimated 3 million Zimbabweans have sought refuge in South Africa. It is Africa's most extraordinary exodus from a country not in open conflict.

The political crisis and resultant economic collapse has led to the implosion of the health system and basic infrastructure which has given rise to a massive cholera outbreak reaching an unprecedented scale and claiming thousands of lives. However, cholera is one aspect of a multifaceted humanitarian crisis that includes poor access to health care; collapsed infrastructure; high prevalence of HIV; political violence; internal displacement as well as displacement to neighboring countries, and food shortages/malnutrition. This situation is by no means new, but it has worsened significantly in the past months, as the political impasse continued and economic collapse accelerated. To make matters worse, there has not been a strong and coordinated international response to the unfolding humanitarian emergency.

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been working in Zimbabwe since 2000 and has been assisting, since 2007, Zimbabweans who have fled to South Africa. Medical teams in Zimbabwe are currently responding to about 75 percent of the suspected cholera cases. Since the beginning of the outbreak in August 2008, MSF alone has treated nearly 45,000 patients and supported treatment of several thousands more through the provision of supplies, logistical support, technical advice and training to Ministry of Health staff. In its regular programs, MSF provides HIV care for more than 40,000 patients with HIV/AIDS, including 26,000 who are receiving antiretroviral therapy (ART), and provides nutritional support to severely malnourished children.

The continuing Cholera emergency

“It is a constant challenge to keep up with increasing patient numbers. We are running out of ward space and beds for the patients.” - MSF staff

The cholera epidemic, which started in August 2008 has been unprecedented in scale for Zimbabwe and still continues today. MSF has treated more than 45,000 cholera patients during this time – which represents approximately 75% of all cholera cases since the outbreak began. The level of MSF’s response has been necessitated by the scale of the epidemic and the inability of local health structures to cope.

Cases have been found in all provinces. More than 500 MSF staff members are presently working to identify new cases and to treat patients in need of care. As of early February 2009, the focus of the outbreak had shifted from the cities to rural areas, where access to health care is particularly limited, but the number of cases in some urban areas are still significant. The epidemic is far from under control. In the first week of February 2009, 4,000 new cases were treated in MSF supported structures alone.

The reasons for the outbreak are clear: lack of access to clean water, burst and blocked sewage systems, and uncollected refuse overflowing in the streets, all clear symptoms of the breakdown in infrastructure resulting from Zimbabwe's political and economic meltdown.

Although MSF has been able to respond to the outbreak on a massive scale – delays and restrictions have been encountered. In December, when the number of cholera patients in Harare had reached a peak with close to 2,000 admissions a week, it took weeks to get permission to open a second empty ward in Harare’s Infectious Disease Hospital to increase the capacity for cholera treatment.

Health system collapse

During the latter half of 2008, public hospitals in Zimbabwe began closing their doors to patients due to a lack of supplies and wages. Patients are turned away, and those who cannot afford private medical facilities are left with no access to health care. MSF clinics in rural areas are seeing increasing numbers of patients coming from urban centers. This is unprecedented for the once exemplary health system in Zimbabwe’s urban areas.

There is currently an accelerated loss of key staff in health centers, especially nurses. The salary received by a nurse is not sufficient to survive due to the astronomical inflation and the increasing bartering and dollar based informal economy1. Many health workers have turned to the informal sector or have fled to South Africa.

There is also a widespread shortage of basic medical materials (syringes, gloves etc) and drugs. Patients are required to buy drugs in most government-run services. MSF is hearing increasing anecdotal evidence of ministry staff requesting that patients pay for medicines that are meant to be free in rural areas. In one hospital in Gweru, surgical patients have been turned away due to a lack of sterile gloves and suture material. Lack of supplies for health facilities also extend to laboratory equipment and laboratory reagents, as well as running water and electricity.

Although staff and drug shortages are not unique to Zimbabwe – and indeed the health structures have the appearance of normalcy - the empty beds and closed doors are indicative of a ruined system, which was once able to provide a high level of medical care, but which is no longer able to cope with the health consequences of the worsening political and economic crisis.

The burden on People living with HIV/AIDS

Life expectancy in Zimbabwe has plummeted to 34 years1, mainly due to the country’s crushing AIDS epidemic. One in five adults are infected with HIV.

The ongoing political upheaval and economic hardship is affecting the ability of patients to access medical care, including HIV/AIDS treatment.

For people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) it is essential that appointments are kept so that treatment is unbroken and proper follow-up is maintained. If treatment is interrupted and patients fail to get their medication on time, the consequences for the patient’s health are serious. Often, their state of health declines rapidly and in the long term, they might develop resistance to first line medications. But keeping appointments has become increasingly difficult. The lack of reliable transport and high transportation costs keep many from reaching health facilities. In addition, the closing of health facilities means that people have to travel farther to receive care.

There are few doctors left in Zimbabwe yet there is a high number of patients requiring ARV initiation. There are an estimated 2,500 patients in Bulawayo waiting for ARVs. Nurses are not allowed to initiate treatment, although they carry out OPD consultations and prescribe antibiotics in clinics.

Despite the shortages of health professionals in Zimbabwe– MSF faces restrictions on bringing staff into the country. Medical doctors are still required to undertake a 3month internship. This has been more problematic since the major hospitals where these internships are performed have closed. Work permits for international staff are difficult to obtain and renew. On average, it takes about 3 months to obtain a work permit. Not only is it essential for these restrictions on MSF to be lifted – but nurses should be empowered to initiate and manage ART patients.

Internal displacement and/or flight to neighbouring countries poses additional challenges to adherence for people on ART. Some patients were afraid of moving and accessing health services due to political violence during the run-off to the elections in June 2008. Poor access to health care created a huge backlog in terms of numbers of patients requiring ART initiation, which can lead to an increase in pre- ART mortality. An enormous number of patients have fled to other countries such as South Africa, but once they arrive they often fear attempting to access the health system due to the threat of arrest and deportation.

Food shortages and malnutrition

From 4 June to 29 August 2008, the government of Zimbabwe imposed a ban on most international aid groups, leading to an almost complete halt to food distributions across the country. Although the ban has been lifted, the implications continue to be felt today. In some parts of the country, food distributions have still not been resumed.

Food shortages are a major problem which is expected to increase even more between February and March 2009, which is the peak of the “hunger season” before the harvest starts.

“The biggest problem for me today in Zimbabwe is the food situation. Some people start to live on wild fruits and eat nothing else – sometimes during a whole week.” – Zimbabwean man at an MSF clinic

In Epworth, MSF has seen a doubling of children on our malnutrition program in December and then again in January. Currently, MSF has been stopped from conducting a nutritional assessment. This hampers MSF’s ability to respond to the nutrition situation in the country and we fear that children are not making it to our clinics.

The lack of availability and affordability of agricultural inputs in Zimbabwe means that food insecurity will continue well into the next season.

"I come from Gutu rural area. I recently married and was staying with my wife and my parents. My wife is 7 months pregnant. We used to live on peasant farming, all of us. Since this year, life has become increasingly difficult. There was not a good harvest in our area because of drought. My wife is starving yet she is pregnant. I decided to come to South Africa to support the 7 members of my family at home. I am hoping to send them some food soon." - Zimbabwean man in his 20s seeking refuge in Musina, South Africa

During the peak in violence, some patients reported to MSF that their crop and food reserves had been destroyed. In Epworth, there was a clear increase in ART defaulters in the MSF programme coinciding with the halting of food distributions and the increased violence surrounding the elections.

Flight to neighbouring countries

The economic meltdown, food shortages, health system collapse, and political violence and unrest have led to a steady increase of Zimbabweans seeking refuge in South Africa in the past decade. Zimbabweans fleeing across the border to South Africa, risk beatings, rape, or robbery by bandits known as the 'guma-guma', or being eaten by crocodiles while swimming across the Limpopo River.

“I am from Zimbabwe. I feel that the situation over there is not being taken serious enough. People are so hungry. When a Somali crosses the border, everybody understands why. Everyone has a picture of the war but this is not the case with Zimbabwe.” - Zimbabwean man in Musina, South Africa

Even with the current collapse in Zimbabwe, the government of South Africa has characterised Zimbabweans in the country as 'voluntary economic migrants' and less than 5% of asylum-seekers are granted refugee status, meaning they do not qualify for legal status that would ensure their protection. In total, there are an estimated 3 million Zimbabweans living in South Africa, most of whom are undocumented.

In South Africa, Zimbabweans live in a constant state of fear that they will be deported. Although the South African constitution theoretically guarantees access to health care and other essential services to all those who live in the country, this policy is not always respected, and the fear of deportation – and more recently xenophobic violence – keeps many Zimbabweans from accessing health care.

Conclusion

The political crisis and resultant economic collapse is manifesting in cholera, population movement, hyperinflation, food insecurity, violence and a lack of access to HIV/AIDS treatment and health care more generally.

Despite the glaring humanitarian needs, the government of Zimbabwe continues to exert rigid control over aid organisations. MSF faces restrictions in implementing medical assessments and interventions. Especially in cases of emergencies where quick action often determines life or death, allowances for a rapid humanitarian response is crucial.

To address the humanitarian issues facing Zimbabwe requires a shift of approach or strategy from a range of political and aid actors – including the UN and donors. There is not only a need for an increased humanitarian response, but also for a move to a more proactive emergency approach based on a recognition of the severity of the crisis in all its manifestations – not just Cholera. Urgent steps must be taken today to ensure that Zimbabweans have unimpeded access to the humanitarian assistance they desperately need.

Now more than ever, an adequate humanitarian response in Zimbabwe will require an increase in "humanitarian space” for independent aid organisations to carry out our work. The Zimbabwean government must facilitate independent assessments of need, guarantee that aid agencies can work wherever needs are identified and ease bureaucratic restrictions so that programmes can be staffed properly and drugs procured quickly.

Donor governments and United Nations agencies must ensure that the provision of humanitarian aid remains distinct from political processes. Their policies towards Zimbabwe must not come at the expense of the humanitarian imperative to ensure that malnourished children, victims of violence, and people with HIV/AIDS and other illnesses have unhindered access to the assistance they need to survive.

- The challenges facing nurses in terms of their salary may see some improvement in 2009 as various UN agencies, donor bodies and NGOs look at paying incentives to Ministry of Health (MoH) staff. However, even with this plan an average nurse would be paid 60 USD/month. This amount would barely cover the transport costs of nurses to travel to and from work

- Healthy life expectancy for women according to WHO 2006. A man’s healthy life expectancy is 37.