by Michiel Hofman, Head of Mission for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) in Afghanistan, and Sophie Delaunay, Executive Director, MSF *

The space to provide neutral, independent, impartial humanitarian assistance in Afghanistan has been lost, and this is having dire consequences for the population

In late 2008, refugees from Farah province, Afghanistan, told Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) aid workers in Iran about the horrific levels of violence they faced inside their country. Some even said that the violence that summer was worse than at any time during the Soviet occupation in the 1980s. One year later, the UN reported that 2009 was the deadliest year for Afghan civilians since the current war began in November 2001.1

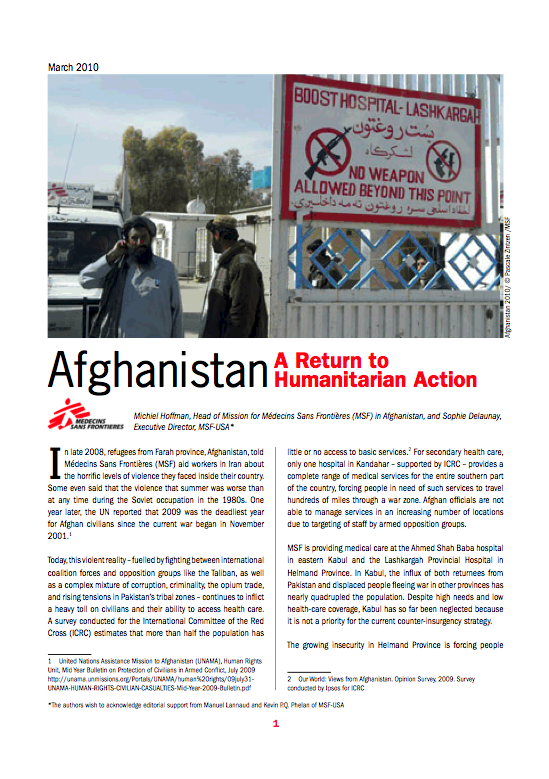

Today, this violent reality – fuelled by fighting between international coalition forces and opposition groups like the Taliban, as well as a complex mixture of corruption, criminality, the opium trade, and rising tensions in Pakistan’s tribal zones – continues to inflict a heavy toll on civilians and their ability to access health care. A survey conducted for the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) estimates that more than half the population has little or no access to basic services.2 For secondary health care, only two hospitals – in Kandahar supported by ICRC, and in Lashkargah supported by MSF – provide a complete range of services for the entire south, forcing people in need of care to go hundreds of miles through a war zone. Afghan officials are not able to manage services in an increasing number of locations due to targeting of staff by armed opposition groups.

MSF is providing medical care at the Ahmed Shah Baba hospital in eastern Kabul and the Lashkargah Provincial Hospital in Helmand Province. In Kabul, the influx of both returnees from Pakistan and displaced people fleeing war in other provinces has nearly quadrupled the population. Despite high needs and low health-care coverage, Kabul has so far been neglected because it is not a priority for the current counter-insurgency strategy.

The growing insecurity in Helmand Province is forcing people to go to extreme lengths to seek either routine or emergency care at often dysfunctional health structures. After the MSF team arrived at the hospital in Lashkargah, a woman nearing the full term of her pregnancy arrived more than 48 hours after being seriously wounded when her village was shelled. She survived but her baby later died of sepsis. Another woman brought in her child who was suffering from measles, revealing how the war has made it virtually impossible to carry out vaccination programs against easily preventable childhood diseases. The mother said eight other children in her village had similar symptoms but could not get to a hospital.

Paradoxically, Lashkargah hospital is piling up with advanced medical equipment – digital x-rays, mobile oxygen generators, scialytic lamps – donated by a range of states including the US, China, Iran, and India or through the Provincial Reconstruction Teams (PRTs). This equipment is usually dropped off with little explanation and no anticipation of maintenance; most of it sits in boxes, collecting dust, unopened and unused.

For several decades MSF provided medical care throughout Afghanistan. In the 1980s, teams set up a network of clinics in areas under the control of a variety of factions. MSF continued to work after the Soviet withdrawal, during the subsequent civil war, the rise and fall of the Taliban, and during the initial stages of the current conflict.

However, ensuring acceptance has been a challenge throughout our presence in Afghanistan. The Soviet Union refused to allow our operations and subsequently bombed several of our health structures, and in 2004, MSF left Afghanistan following the targeted assassination of five staff members. When the organization returned in 2009, teams found that the conditions needed for strictly impartial medical assistance had deteriorated almost to the point of disappearing.

One factor contributing to this deterioration in independent humanitarian assistance has been the deadly lack of respect for health care workers and facilities shown by all of the belligerents involved in the conflict. Hospitals, clinics, and medical personnel have been targeted by armed opposition groups like the Taliban, while Afghan government and international forces have repeatedly raided and occupied health structures. A second, related factor has been the co-optation of the aid system by the international coalition – at times with the complicity of the aid community itself – to the point where it is difficult to distinguish aid efforts from political and military action.

In short, the space to provide neutral, independent, and impartial humanitarian assistance in Afghanistan has been lost, given away, or taken, and this is having dire consequences for the population. Whether it is possible to regain and defend this space will not only affect the provision of assistance in Afghanistan, but in other conflicts as well.

Losing Ground for Humanitarian Action

The international military intervention in Afghanistan was initially meant to bring down the Taliban, a regime that hosted al-Qaeda before the 9/11 attacks on the U.S., with the eventual objective of defeating al-Qaeda. In his speech on December 1 at West Point, President Obama reiterated a pledge to “disrupt, dismantle and defeat al-Qaeda in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and to prevent their return to either country in the future.” To understand how the national security objective of the US led to the politicization and instrumentalization of assistance in Afghanistan, two closely related strategies adopted by the US and its allies as a means to achieve their goals in Afghanistan require examination.

The first strategy is based on the assumption that sustainable security for the West in general and the U.S. in particular depends on the stability of failed or failing states that risk provoking extremism among impoverished populations. By following this theory, conflict resolution or peace building is not enough, and sustainable security will only be achieved through economic development and a coherent western-style nation-building process that fosters democracy, human rights, justice, and good governance.

This doctrine attempts to integrate relief and development assistance into a broader political agenda, and now forms one of the pillars of the 3D strategy – Defense, Diplomacy and Development – employed by international forces in Afghanistan and elsewhere. Secretary of State Clinton referred to “smart power” to define this approach which aims to use foreign assistance – “soft power” – to better serve the U.S. foreign policy and national security interests.

The second strategy is the military’s direct and immediate instrumentalization of assistance with the aim of “winning the hearts and minds” of the population as part of its counterinsurgency (COIN) strategy. According to this line of thought, public services are provided in combat zones in order to gain control over the population and deny support to insurgents.

The overlap between these two security strategies laid the complex groundwork for integrating assistance into political and military agendas.

Under the auspices of the United Nations, participants in the Bonn Conference in December 2001 agreed that developing a Western-style democracy would bring peace and security to the region. By 2004, the United Nations (UN) and the broader international aid community began considering Afghanistan as a “post-conflict” setting, leading the Afghan government and donor countries to urge aid agencies to conduct capacity-building activities in support of their efforts to establish democracy.3

The long-term security goals of the U.S. and its allies began echoing the developmental and human rights ambitions of a large part of the international aid community that also believes the promotion of democracy and good governance can bring peace and stability.

Many aid groups welcomed and actively supported this approach. In June 2003, more than 80 organizations – including major U.S. aid agencies – called on the international community to expand NATO’s International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) and provide the resources needed “so that democracy can flourish” and “improve the prospect for peace and stability for the Afghan people and the world."4 By making such a call, a majority of the international aid system aligned its efforts with the West’s security agenda, much the same way some groups did decades earlier in the struggle against the communist regime in Vietnam.5

This solidified the perception that the entire aid system was supporting the Afghan government and international coalition forces in their effort to defeat the insurgency. This sentiment combined with then-President Bush’s rhetoric of the Global War on Terror contributed to an increased polarization of armed opposition groups like the Taliban to the point where both international and national staffs of organizations from countries supporting the Afghan government were becoming viewed as legitimate targets.

That these same international organizations were aligned with the West during the Cold War may have reinforced this view. Testimony from MSF and others to the U.S. Congress in the 1980s may have contributed to U.S. policy of supporting the most radical Islamic mujahideen groups during the Soviet war.6

Peace and stability are no doubt noble objectives, but when aid organizations seek to transform a society by promoting the strategy of one of the belligerents in the midst of a war, they are no longer seen as impartial by all sides and subsequently lose the ability to access and provide assistance to all people in need. For this reason, it is nearly impossible for any organization to simultaneously provide humanitarian assistance while also looking for ways to resolve a conflict.

Co-optation of Assistance: Humanitarian Camouflage

As described in the mid-1960s by the French military officer and scholar David Galula, counterinsurgency (COIN) warfare shifts the focus from the control of territory to the control of the population.7 Insurgents, unlike military troops, don’t need to occupy territory. Their strength comes from their ability to hide among the population and conduct spectacular operations against counterinsurgency forces.

Thus the counterinsurgent’s objective is to gain the will of the population and deny support to the insurgents. Or as General Stanley McChrystal, commander of the U.S. and ISAF forces in Afghanistan described it: “The people of Afghanistan represent many things in this conflict – an audience, an actor, and a source of leverage – but above all, they are the objective.”8

The militarization of emergency assistance in service to the U.S.-led COIN strategy in Afghanistan emerged concretely early in 2002 with the deployment of U.S. PRT units consisting of both military and civilian components. These units initially attempted to facilitate reconstruction efforts in provinces outside of Kabul but eventually became the “forward-operating” civilian body of coalition forces tasked with neutralizing “environmental threats” on the battlefield. Then-Secretary of State Colin Powell went so far as to call aid workers “force multipliers” in the war effort.

President Obama has chosen to continue and reinforce this strategy in Afghanistan. In March 2009 he announced a “civilian surge” with the deployment of hundreds of governmental agency workers to reinforce non-military capacity in the country. The role of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) in the war effort has been strengthened by increasing significantly its staff and operations working in coordination with the PRTs in Afghanistan.

According to the “U.S. Government Integrated Civilian-Military Campaign Plan for Support to Afghanistan” elaborated by General Stanley McChrystal and U.S. Ambassador to Afghanistan, Karl Eikenberry in August 2009, all of the civil-military elements operating in the same province should coordinate and synchronize the full spectrum of U.S. organizations, including private aid groups, as well as the UN and the whole range of Afghan partners operating in the area.9

In such a context, aid becomes “threat-based” rather than “needs-based” – that is, it is deployed according to military objectives not impartial assessments of humanitarian needs. Assistance thus becomes just another weapon at the service of the military, which can condition, deny or reward relief to those who fall in or out of line with its larger security agenda. A particularly egregious example of this occurred in 2004, when coalition forces distributed leaflets that threatened to cut off assistance unless the population provided information on al-Qaeda and Taliban leaders.

Intelligence gathering from integrated civilian agencies is another means of fulfilling COIN objectives that also erodes the space for impartial humanitarian assistance. Richard Holbrooke, the U.S. Special Representative for Afghanistan and Pakistan, recently confirmed this, stating that most of the information about Afghanistan and Pakistan comes from aid organizations on the ground.10 This outraged many in the aid community as it reinforced the perception that they spy for the U.S.

The abuse of identified symbols of neutral humanitarian actors by the military can also contribute to greater confusion between military and aid intentions. It is only recently that NATO agreed to not use white cars because white is largely seen as the color of impartiality and independence. It would be naïve, however, to believe that militaries will stop using “humanitarian camouflage” as it tries to win the psychological war and protect its troops.

Instrumentalizing assistance and invoking the humanitarian imperative has a further advantage for militaries: it seduces public opinion back home and can provide cover to policy-makers for conducting foreign wars. By appealing to an unquestionable moral rationale, a humanitarian war narrative forecloses any discussion on the concrete objectives, costs and benefits of armed intervention for both the intervening countries and the society in which it takes place. In this sense, wars in the 1990s in Somalia, Iraq, and the former Yugoslavia – all labelled humanitarian – were probably the most extreme examples. In his Nobel lecture, President Obama reiterated a belief "that force can be justified on humanitarian grounds, as it was in the Balkans, or in other places that have been scarred by war."11

Health Care Facilities Drawn Into the Battlefield

Afghanistan has some of the worst health indicators in the world12 with staggeringly high infant and maternal mortality. People in need of any medical services must take extreme risks to travel through conflict areas to reach a health structure, usually a poorly functioning one. When MSF assessed the hospital in Lashkargah, there was a 30% mortality rate – largely the result of absent staff and patients’ inability to arrive until a condition had become life-threatening. Since civil wars and counterinsurgencies are a competition for the support of a population, the provision (or denial) of health services becomes a key asset for all belligerents. This has led warring parties in Afghanistan to see healthcare workers and facilities as part of the battlefield.

Armed opposition groups, for example, have targeted health structures and medical personnel for their own strategic reasons. In May 2009, a clinic in Nadir Shah Khot in Khost was destroyed and staff threatened by an armed group and in November suspected militants burnt a health clinic down in the Daman district of southern Kandahar province.13, 14 Armed opposition groups are also linked to the murders, attacks, and abduction of aid workers, including an increasing use of improvised explosive devices (IEDs).15

In late August, Afghan and NATO forces raided a clinic in Paktika following reports of an opposition commander being treated inside, killing 12 insurgents with the support of helicopters firing at the building.16 One week later, U.S. forces raided a hospital supported by the Swedish Committee for Afghanistan (SCA) in Wardak Province. Soldiers searched the hospital, forced bed-ridden patients out of rooms, and even tied up staff and visitors. On their way out they ordered the staff to report admissions of any suspected insurgents to the coalition forces. That same month, the director of Helmand’s health department denounced the occupation of a clinic by Afghan and U.S. forces in Mianposhta saying “people are scared and do not want to go to this clinic.” The clinic is now closed.

The “civilian surge” in Afghanistan required development aid workers to seek armed protection from a large array of international forces and private security firms. This has lead to a wide variety of soldiers and mercenaries freely circulating in hospitals and health centers with their machine guns, turning such structures into battlefields. Officers from Afghanistan’s intelligence services, the National Directorate of Security, also regularly interrogate or arrest patients destroying the confidentiality between medical staff and patients.

Of course military units can be involved in aid operations. But in carrying out such activities, they must clearly distinguish themselves by, for example, wearing their uniforms and respecting the neutrality of the facilities where aid actors are working.

In addition to the humanitarian imperative of creating a safe space for the wounded and sick, calling for the respect of medical facilities and personnel – as stipulated in the Geneva Conventions – has a major practical effect: it ensures that medical facilities do not become tactical targets and in turn deny health care to a population.

The Elusive Principles of Humanitarian Action

In June 2009, the U.S. military invited a diverse range of organizations involved in emergency relief, development and conflict-resolution activities in Afghanistan to a conference at West Point aimed at bridging what they called “the cultural gap” existing between the military and non-governmental organizations. A background document circulated before the conference concluded that both sides had to come to a mutual understanding because they share “some common purposes such as preventing conflict and creating stability in fragile and failing states.”

This demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of humanitarian principles. The line separating humanitarian and military action is one that by definition under International Humanitarian Law (IHL) can not be bridged. While humanitarian organizations such as MSF may share the same area of operations with military forces, our purposes are not the same.

Delivering emergency medical aid in war zones does not make MSF a pacifist organization, nor do we judge the legitimacy of war ends pursued by any belligerents in a conflict. While we demand adherence to IHL – particularly the respect for patients, medical ethics, and health staff and structures – our aim is not to end wars, bring peace, build states, or promote democracy. The only ambition of humanitarian action is to limit the devastation of war by helping people survive in decent condition, no matter what side of a frontline they may find themselves on.

Impartial humanitarian assistance requires acceptance from all communities and warring parties – whether national governments, armed opposition movements, international forces, or even criminal gangs. In all conflicts, creating working space needs to be negotiated and then maintained over time by actions that demonstrate we are only motivated by the wish to provide lifesaving medical assistance. Nostalgia for a Golden Age when access and protection were granted automatically to aid workers is pure fantasy, and Afghanistan is no exception.

With the multiplication of aid actors, some combining a variety of goals in one organization – relief, development, human rights, conflict-resolution, civil society promotion, justice, rule of law – claims of neutrality, independence and impartiality can at times seem hypocritical or simply invocations aimed at reinforcing an organization’s own illusions of purity.

Neutrality is often abandoned for a so-called “pragmatic” approach by organizations hoping to participate in the integration of development and nation-building efforts. Such an approach chooses to sacrifice one’s ability to respond to immediate needs for the sake of a brighter future.

Although there is no fundamental opposition between relief and development assistance, there is a need to make distinctions, in particular when a conflict is ongoing. No matter the intent, organizations that engage in a development or nation-building agenda during a conflict will be perceived as taking sides. For the sake of preserving the space for impartial humanitarian assistance, in war zones multi-mandate organizations should make a choice between relief and development assistance, a choice between saving lives today or saving societies tomorrow.

Independence is also compromised by the need for financial resources as many aid organizations rely on state-funding for survival. This gives donor countries undue leverage for co-opting assistance in service of their political needs and leads beneficiaries to question the motives of aid workers. (MSF teams in Pakistan were asked repeatedly by displaced people this past summer, “Where do you get your funds?”) In Afghanistan, the majority of countries who fund Western aid organizations are part of the international coalition. But financial independence does not automatically make an organization a neutral or impartial actor – that can only be obtained through action.

In the struggle to access those most in need, the only tool humanitarian aid workers have is the clarity and transparency of our intentions. Since it is difficult to distinguish among the various actors that make up the alphabet soup that is the aid system in a place like Afghanistan today, humanitarian action requires, at minimum, the practical demonstration of neutrality, independence, and impartiality, probably at the price of taking distance from the larger aid community. Even so, there can be no illusion that such actions will guarantee the safety of humanitarian aid workers who are inherently vulnerable in any war.

The Humanitarian Imperative and the Ethic of Refusal

Today, the humanitarian community has lost the acceptance among the population and the various parties to the conflict in Afghanistan that it relied on for more than twenty years. As a result, it has also lost the ability to provide relief assistance in large parts of the country.

The instrumentalization of humanitarian assistance by political and military actors to serve counterinsurgency purposes played a major part (and led to the occupation of medical facilities by military forces – both literally and figuratively.) A large portion of the aid community itself supported this co-optation – voluntarily or not – by believing that assistance should go beyond the basic humanitarian imperative of saving lives and be directed toward the broader goals of nation-building, peace, and development.

Such an approach has compromised humanitarian principles and eroded the working space needed to provide humanitarian assistance. While both relief and development may be well-intentioned and are not necessarily opposed to one another, there is a major operational incompatibility between the two in war.

These principles are essential pre-requisites for relief workers. They are practical tools that help ensure respect for humanitarian action by all parties in a conflict. Neutrality, independence, and impartiality are obviously not as critical for building roads and schools or for promoting the rule of law, as they are for an emergency room where wounded civilians and non-combatants from different factions may seek lifesaving medical care. In the latter case, compromises can lead to deliberate attacks on facilities, patients, or medical staff, thus reducing access to medical services for an entire population trapped by war.

MSF has built its action and identity on an ethic of refusal that directly challenges any logic that justifies the premature and avoidable death of a part of humanity in the name of a hypothetical collective good.17 In Afghanistan today, the organization again refuses to participate in a collective, integrated effort that does not aim to alleviate immediate suffering. And after eight years of war, emergency medical care for Afghans should not depend upon the parties waging it.

* The authors wish to acknowledge the editorial support of Manual Lannaud and Kevin P. Q. Phelan of MSF

- United Nations Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA), Human Rights Unit, Mid Year Bulletin on Protection of Civilians in Armed Conflict, July 2009 UNAMA HUMAN RIGHTS CIVILIAN CASUALTIES Mid Year 2009 Bulletin

- Our World: Views from Afghanistan Opinion Survey, 2009. Survey conducted by Ipsos for ICRC

- Afghanistan: Humanitarianism under Threat Antonio Donini, March 2009

- Afghanistan: A Call for Security, International Council of Voluntary Agencies (ICVA), July 2003

- Private voluntary aid and nation building in South Vietnam: The humanitarian politics of CARE, 1954-61 Delia T. Pergande, PEACE & CHANGE, Vol. 27, No. 2, April 2002

- Becoming What We Seek to Destroy, Chris Hedges, May 2009, Truthdig, Becoming What We Seek To Destroy

- Counterinsurgency Warfare: Theory and Practice, David Galula, 1964

- Commander’s Initial Assessment, General Stanley McChrystal, US Army, August 30, 2009

- eikenberryandmcchrystal.pdf

- Envoy laments weak US knowledge about Taliban, Robert Burns, Associated Press, April 07, 2009

- http://www.google.com/hostednews/ap/article/ALeqM5iRWjTDaT4JuS0nFj9APZAues8vjAD9CGFID00

- World Health Statistics 2009, World Health Organization

- The Anso Report PDF

- www.khabaryal.com, Afghanistan, November 23, 2009

- ANSO.pdf

- Fury at Nato's Afghan clinic raid, BBC, August 28, 2009

- The Sacrificial International Order and Humanitarian Action, Jean-Herve Bradol, In the Shadow of “Just Wars”, Cornell University Press, 2002